Brexit: Who will blink first in UK-EU stand-off?

- Published

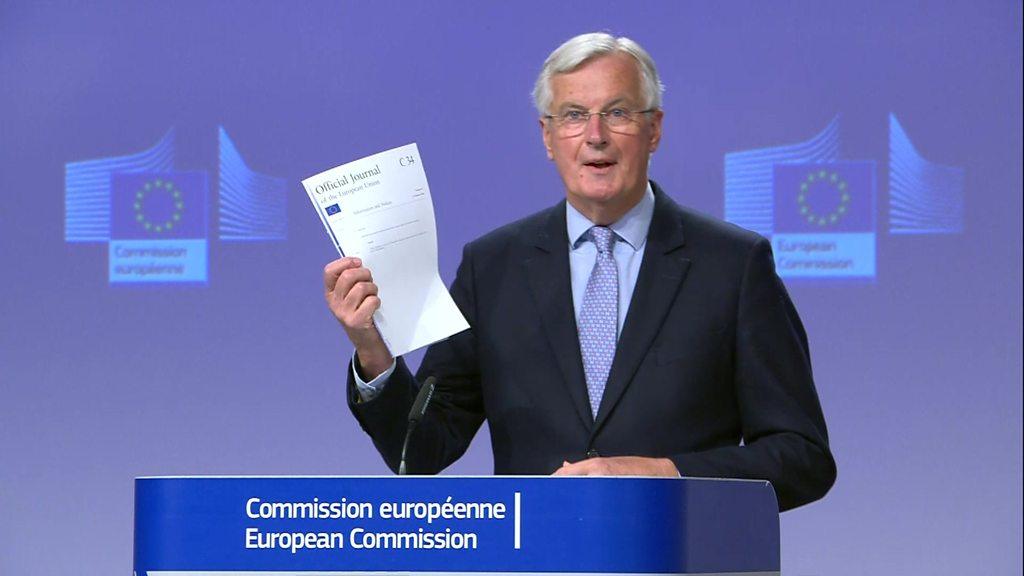

Brexit: Barnier on UK approach to EU trade talks

"Plus ça change," you could say.

Round four of EU-UK trade talks... cue yet another downbeat assessment from both sides' chief negotiators. "We can't go on like this," lamented the EU's Michel Barnier. "Progress remains limited," noted the UK's David Frost.

But before you rush to join the "no-deal-is-now-the-most-likely-outcome" school of thought, consider this: while both sides continue to insist - loudly - that their position will not waver (on all issues linked to national sovereignty for the UK; on anything associated with the single market for the EU), those assurances could also be viewed as a message aimed at domestic audiences, while both sides consider - quietly - what compromises they might actually make.

Back in February, the UK threatened to walk away from talks this month if there were no concrete signs of progress.

And here we are, with ongoing gaping differences between the two sides - on fishing, competition regulations, the form of the deal as well as the content.

Yet the expectation now is that Boris Johnson will use an EU summit in a couple of weeks to try to publicly "reset" negotiations. Inject some dynamism into them. Or at least be seen to be doing so.

UK PM Boris Johnson is expected to try to publicly reset talks

After this summit-by-video-conference with the presidents of the European Commission and the European Council, negotiating rounds are likely to be stepped up. They'll also, depending on Covid-19 restrictions, become face-to-face talks rather than screen-to screen, in the hope that could help the EU and UK better understand one another's position.

But frankly, after four rounds of negotiations, each side is already all too familiar with the attitude and intentions of the other.

What's needed now is movement. Call it blinking. Call it compromise. Call it concessions or whatever you will. Without it, there will be no deal. That much is clear.

The coronavirus turmoil has meant political leaders have rather overlooked these post-Brexit EU-UK negotiations. But they are fast reappearing on the UK's political horizon. The rest of Europe will probably sit up and take notice this autumn, with the clock ticking down to the end of the year - if the government stands firm on not extending talks beyond that date.

Brussels is already beginning to show some ankle.

The EU will need to “evolve its position to reach an agreement” with the UK in trade talks, says the UK's chief negotiator

Sift carefully through Michel Barnier's rhetoric on Friday. Amongst accusatory statements and words of disappointment aimed at the UK, you'll find hints of potential EU wiggle-room: a possible softening of its demands on state aid rules and fishing quotas.

When I asked him, Mr Barnier also admitted that, if a deal were close this autumn, there would almost certainly be what he called a "dense" period of last-minute negotiations.

In other words: pressure to find compromise.

And what of Angela Merkel? Prominent UK politicians have often looked to her - and to German car manufacturers - to push for a favourable deal with the UK.

Germany will shortly take over the EU's six-month rotating presidency. Will Mrs Merkel want to "preside" over a no-deal break-up with key partner UK - something which would also blot her legacy in her last term as German Chancellor?

The UK has so far insisted it won't extend the transition period

Perhaps more so than other EU leaders, Angela Merkel has always been focused on the bigger picture. A desire not just to keep the UK close in trade terms but also on the world stage, dominated these days by unpredictable leaders in China, Russia and the US.

But in the end her priority (often misunderstood by the aforementioned prominent UK politicians) is not lucrative trade with the UK. She prefers to protect the vastly more lucrative - certainly from Germany's perspective - single market.

Chancellor Merkel's focus now is on helping to rebuild that market after the devastation of Covid-19 - not on compromising its rules to have a favourable trade deal with an EU outsider, the UK.

So: concessions, yes. But not at any price. For now, Brussels waits for a sign that the UK too is willing to make what it calls realistic compromises.

The government recently floated the possibility of reducing its aim of 100% tariff-free trade, to 98% or 99% in order to allay EU fears of unfair competition. But Brussels dismissed the idea as not addressing its concerns.

Ultimately, the sense in Brussels is: if there is to be a deal by the end of this year, that (political) decision will be made in Downing Street. Not round the EU table.

- Published5 June 2020

- Published27 May 2020