Coronavirus: Island isolation over as Greece lets tourists back

- Published

Santorini is renowned for its domed churches

Every morning Michael Ermogenis leaves his house in Oia, Santorini, to walk his dog. The picturesque island's famous domed churches and sunset views helped draw more than two million overnight visitors last year.

For months he has been able to wander the marble paths all day and barely see another person, as the coronavirus pandemic has stopped tourism. But on Monday that is all set to change, as Greece reopens its borders with the aim of kick-starting its tourist season.

Usually the crowds and traffic on Santorini are so hectic that it can take Michael up to an hour to leave his village. Tourist numbers had been growing so much that the EU warned they were putting "the future of the destination at risk".

"It's just unbelievable," he says. "I feel like I've been given the keys to Disneyland. But at the same time, I know this hasn't been done for my benefit. It's a major global disaster."

Can Greece reinvent its tourism model?

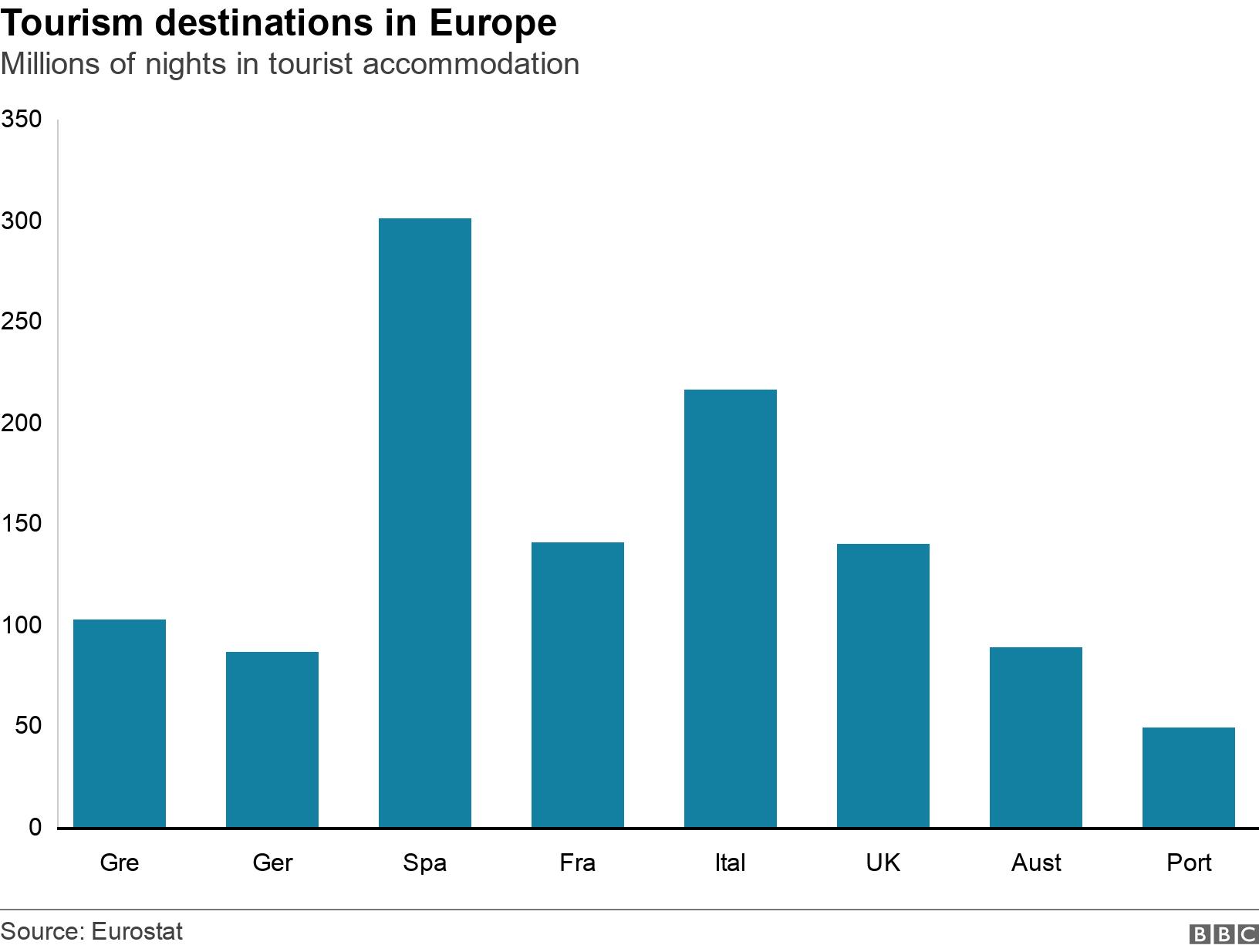

The halt to global travel has proved devastating to a Mediterranean country such as Greece, where tourism makes up as much as 30% of economic output and commands up to one in five jobs.

It welcomed a record 33 million visitors last year, and for many islands tourism is the main source of private sector employment.

Some island residents are now wondering if this could be an opportunity to move to a more sustainable tourism model.

"Right now, over-tourism as a subject has come off the boil," says Michael Ermogenis. He was previously so worried about visitor numbers that he started a Save Oia campaign, erecting signs around the village asking tourists to treat their surroundings with respect.

"The question is, how soon will it become an issue again, unless the authorities try do things in a more thoughtful, strategic way?"

How Greece is reopening for tourism on 15 June

Thermal imaging cameras are also being used in Greek stations

Greece begins phase two, allowing international flights into Thessaloniki airport; until now only Athens was open. Flights resume from much of Europe, Israel, Japan, Australia and New Zealand:

Arrivals by air - from 29 countries considered low-risk - will face random tests for Covid-19

Arrivals from some European countries deemed higher risk, external, including Belgium and the UK, will face compulsory testing. A negative result will require a week in quarantine, two weeks for a positive result

Land border arrivals are allowed from Albania, North Macedonia and Bulgaria and face random testing

Seasonal hotels are allowed to reopen.

1 July: International arrivals allowed into all Greek airports and sea ports, with random testing.

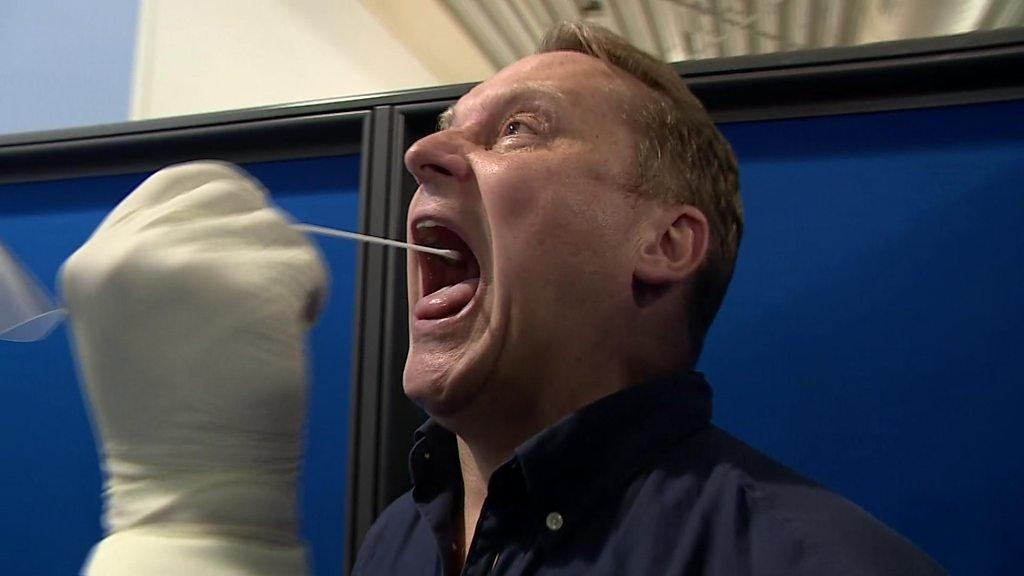

The BBC's Quentin Sommerville arrived in Athens airport last month to see how Greece tested travellers

On the nearby island of Mykonos, famous for its parties and celebrity visitors, Stacey Harris-Papaioannou admits she has been enjoying having the beaches largely to herself.

"But nice as it is, we can't pay our bills with sand," she laughs, explaining that she makes an income renting accommodation to seasonal workers.

The waters off Mykonos are for now quiet

Cruise ships have been one of the islanders' biggest complaints, she says.

"On any given day we might have seven of them show up at once, and the island gets deluged with an extra 20,000 people within an hour," she says. For years, she and others have been calling for boat arrivals to be staggered.

A sight from the past: but when will cruise ships return to Mykonos?

The pandemic has put paid to the cruise industry for now and this year none of the big ships will be docking in the harbour.

Many Mykonians are happy about this, although some businesses such as cafes and mini-markets will take a hit.

Another problem has been the pressure on infrastructure, as capacity has not increased to keep up with visitor numbers.

Mykonos frequently experiences blackouts due to excessive energy use. Waste management too is a huge issue.

Santorini has no recycling facilities, just an illegal dumpsite not up to EU standards.

How tourism helped build modern Greece

Tourism has been used by successive Greek governments as a means of resuscitating the country after crises.

In the 1950s, the government built five-star, state-run hotels in a bid to attract upmarket visitors after World War Two.

After the military dictatorship took power in a coup in 1967, the focus turned to mass tourism, and continued after it fell in 1974.

Tourism has helped Greece recover from the 2008 financial crisis, too, although many argue it has not been properly managed.

"There is still a lack of specific policies regarding tourism flows," says Prof Efthymia Sarantakou at the University of West Attica.

"One basic weakness is that the government structure does not give regional authorities the power to manage and regulate tourism at a local level."

Could Greece use the pandemic to change?

Another complaint in Greece is that over-reliance on tourism has led to a deluge of low-skilled, badly paid seasonal jobs.

"It's an industry that employs a lot of women, migrants and young people worldwide," says Kristina Zampoukos, from the department of tourism studies at Mid Sweden University.

"It's a sector that's not highly valued or paid because of its association with feminised skills, such as cleaning, serving and caring for others."

Other destinations that have previously suffered from over-tourism, such as Venice and Amsterdam, have already declared they are using the pandemic as an opportunity to introduce more sustainable models.

So far the Greek government has not made any similar moves.

For the moment many islanders are focused on whether they can make an income and avoid a second wave of the virus. But they will be wary of seeing the old problems return.

- Published21 May 2020

- Published2 July 2020