Ukraine floods: Why climate change and logging are blamed

- Published

Floods washed away homes and roads in western Ukraine in late June

When flooding hit almost 300 towns and villages in western Ukraine last week, Prime Minister Denis Shmygal said they were the biggest since the 1990s. Climate change is part of the story, but illegal logging and deforestation are also being blamed for the scale and speed of the floods.

"This stream was so small you could walk across it. I couldn't imagine it turning into the devastating flood," said Pavlo Gutsulyak, a villager in the Carpathian mountains who has lost his home.

Rivers rose to 3m (10ft) and the high water devastated roads, bridges, dams and property.

Scientists say climate change is causing unpredictable shifts in weather

An estimated 500km (310 miles) of roads were damaged and some routes destroyed. The damage is still being counted and the government has pledged millions towards the cost of rebuilding.

But that will only add to the economic burden for a country already expecting a decline of up to 8% of gross domestic product (GDP) this year.

What's happening to the climate?

Scientists say Ukraine is seeing fast changes to its climate and neither the government nor the population is prepared for it.

"Winters in Ukraine have disappeared," says Oksana Maryskevych, a scientist from the Institute for Environment of the Carpathian Mountains. "Generally we don't have clearly differentiated seasons any more. Summer has become very hot. There's a lot of torrential rain when in just two days we see an entire month's precipitation."

Flooding has destroyed infrastructure as weather conditions change

For Ukrainians it has come as a surprise to see their continental climate seem more like the Mediterranean.

Sporadic strong winds, dry spells and heavy rain are becoming increasingly common. In the north they are seeing raging wildfires, sandstorms and in the mountains increasing floods.

How bad is the logging?

Since 2001, there has been a threefold increase in logging on mountain peaks in the Carpathians, says environmental activist Dmytro Karabchuk of the NGO, Forest Initiatives and Communities.

The prime minister insists logging has gone down by a fifth in the past five years but environmentalists say that is down more to a decrease in market demand than carefully considered state policy.

Areas where trees have been felled in the mountains are clearly visible

Up to a third of all logging in Ukraine is illegal, according to independent experts and the Carpathians are one of the worst regions affected by the practice of clear-cutting, or felling most of an area's trees.

Mr Karabchuk says no-one is registering the scale of illegal logging in the Carpathians. However, the many bald spots in the mountains are now clear for all to see.

What happens to the logs?

Wood cut illegally from the Carpathians is often exported. British NGO Earthsight spent 18 months investigating allegations of Ukraine's Carpathian timber being sold through a Romanian intermediary to Swedish multi-national furniture giant Ikea.

Illegally felled beech trees had been used to make some of the company's best-known wooden products, it alleged.

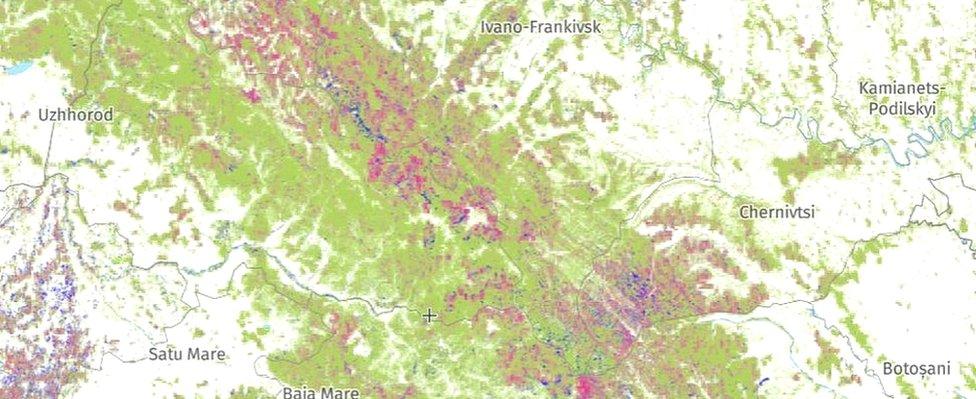

The purple areas on this map of western Ukraine and Romania to the south show the loss of tree cover since 2001

Ikea said this week it was deeply aware of the global issue of illegal logging and had begun an independent audit of its timber supply chain in Ukraine.

"We emphasise that Ikea does not use illegally logged timber for the production of its goods," it said. "If we receive information that wood that doesn't meet these requirements entered or could enter the company's supply chain, we are taking urgent measures."

Mr Karabchuk said that deforestation in the Carpathians had made the floods even more devastating. "Forests keep more water in the ground. With them in place, water gets down slopes more slowly," he says.

Plant debris littered flooded villages in Ukraine

Activists are also annoyed that Soviet-era tractors have been used which damage the soil, and the soil then absorbs less water.

Meanwhile, the Forest Stewardship Council has said it will consider withdrawing certificates from loggers who fail to comply with its standards of forest management.

While many Ukrainians who live in the area see logging as a well-paid job in a region with few employment opportunities, they are also seeing the effects on their local community.

Logs left on river banks were caught up in the floods and for Pavlo Gutsulyak that meant his home was badly damaged.

"I understand now that it's necessary to clear up the river and plant more forests," he told BBC Ukrainian.

There is an added problem that lessons from earlier floods appear not to have been learned.

After large-scale floods in 1998, Ukraine did implement some preventive measures. But scientist Oksana Maryskevych believes of all the measures planned for the Tisa River basin only 10-20% were carried out at best.

"They are always cheaper than the cost of the flood damage," she says.

For parts of western Ukraine the task ahead is becoming a matter of survival. Authorities will now have to fortify river banks and clean up river beds, build reservoirs in the mountains and protect the forests that remain.

Men clear the streets in the Ukrainian village of Lanchyn