Turkey-Greece tensions escalate over Turkish Med drilling plans

- Published

The Oruc Reis is escorted by Turkish navy ships in a photo provided by the defence ministry

Greece and Turkey are planning rival naval exercises off Crete amid an escalating row over energy claims in the Eastern Mediterranean.

The two neighbours have seen frequent flare-ups, but this latest spat over gas reserves and maritime rights has prompted fears that tensions could escalate further. Several other countries have stakes in the dispute and the two Nato allies are engaged in a war of words.

Greece has vowed to defend its sovereignty, and the EU, of which Greece is a member, has appealed for dialogue.

How have relations soured?

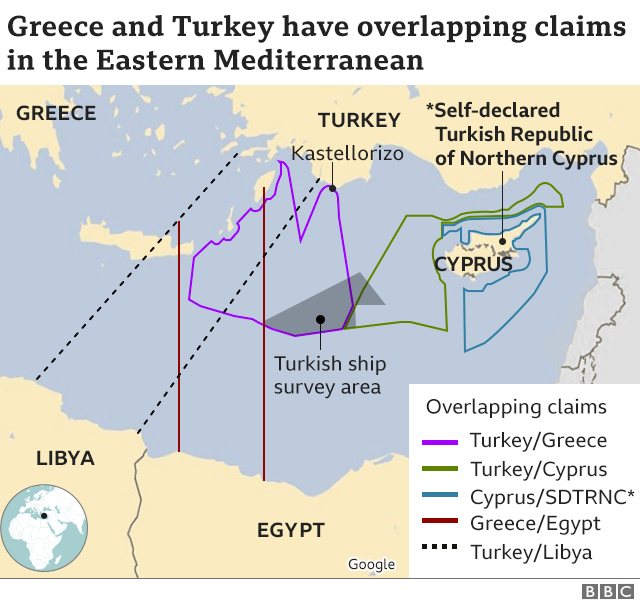

Turkey and Greece have competing ambitions over gas reserves and they disagree profoundly over who has rights to key areas of the Eastern Mediterranean. They have laid claim to overlapping areas, arguing they belong to their respective continental shelves.

In July, Turkey put out a naval alert - known as a Navtex - that it was sending its Oruc Reis research ship to carry out a drilling survey in waters close to the Greek island of Kastellorizo, a short distance from the coast of south-west Turkey.

Turkey has rejected Greece's complaints over the ship's planned voyage as against international law

The survey alert covered an area between Cyprus and Crete. At the time the ship did not weigh anchor in the Turkish port of Antalya. But the alert prompted alarm in the Greek military, and fears of a clash near Kastellorizo.

Relations between Greece and Turkey have been icy for months. The two countries have quarrelled over migrants crossing into Greece; then Greece was appalled when Turkey decided the Hagia Sophia museum in Istanbul, for centuries an Orthodox Christian cathedral, would be turned back into a mosque.

After German intervention, there was a commitment to dialogue and calm was apparently restored. But then in early August Greece signed a deal with Egypt to set up a maritime zone that infuriated Turkey. The talks were called off and the Oruc Reis left port on 10 August. By late the next day the Oruc Reis was reported to be sailing in waters between Crete and Cyprus.

As Greek and Turkish naval ships shadowed the Oruc Reis, a Turkish frigate collided with a Greek ship and President Erdogan warned: "We will not leave unanswered the slightest attack."

This Turkish drilling ship, Fatih, went into operation off Cyprus last year

Why the flare-up?

Turkey and Greece are on separate sides in a race to develop energy resources in the Eastern Mediterranean.

In recent years, huge gas reserves have been found in the waters off Cyprus, prompting the Cypriot government, Greece, Israel and Egypt to work together to make the most of the resources. As part of that agreement, energy supplies would go to Europe via a 2,000km (1,200-mile) pipeline in the Med.

Last year Turkey stepped up drilling to the west of Cyprus, which has been divided since 1974, with Turkish-controlled northern Cyprus only recognised as a republic by Ankara. Turkey has always argued that the island's natural resources should be shared.

Then, in November 2019, Ankara signed a deal with Libya that Turkey said created an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) from the Turkish southern coast to Libya's north-east coast. Egypt said it was illegal, and Greece said it was absurd as it failed to take account of the Greek island of Crete, midway between the two countries.

At the end of May, Turkey said it planned to start drilling in the coming months in several other areas further west, alarming EU members Greece and Cyprus.

Several licences have already been issued to Turkish Petroleum to drill in the Eastern Med, including off the Greek islands of Rhodes and Crete.

"Everyone should accept that Turkey and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus cannot be excluded from the energy equation in the region," said Turkish Vice-President Fuat Oktay in July.

On 6 August, Greece and Egypt hit back with a deal of their own, forming an exclusive economic zone that Greece said would cancel out the Turkish agreement with Libya.

As well as despatching its survey ship, Turkey has said licences for exploring new areas will be issued in the "western part of our continental shelf" from the end of the month. It has also announced the discovery of major gas reserves in the Black Sea,

Why have other countries got involved?

While several countries have stakes in energy resources in the Eastern Med, the conflict in Libya has also created regional rivalries.

Turkey backs Libya's Government of National Accord (GNA), based in the capital Tripoli and recognised by the UN. But the UAE, Russia and Egypt support Libya's eastern strongman Gen Khalifa Haftar. France has repeatedly denied backing Gen Haftar but tensions between Paris and Turkey spilled over when France accused the Turks of violating the Libya arms embargo.

That animosity has extended to the drilling row too. The EU backs Greece's position and France has temporarily deployed a frigate and two Rafale fighter jets in the Eastern Med for joint naval manoeuvres with Greece off the island of Crete. The UAE has also reportedly sent some F-16s to Crete to take part.

Turkey is also holding rival exercises in the same area south of Crete.

The US has urged the two sides to talk and Nato Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg has called for the situation to be "resolved in a spirit of Allied solidarity and in accordance with international law".

Germany is seen as key to taking the heat out of the crisis and Foreign Minister Heiko Maas travelled to Athens and Ankara in late August, warning that "the least spark can lead to catastrophe".

What are the legal issues?

Many Greek islands in the Aegean and the Eastern Mediterranean are within sight of the Turkish coast, so issues of territorial waters are complex and the two countries have come to the brink of war in the past.

If Greece were to extend its territorial waters from six miles to the maximum of 12 allowed internationally, Turkey argues its sea routes would be severely affected.

"No way Turkey will consent to any initiative trying to lock the country to its shores," Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has complained. Turkey has embraced a doctrine known as Blue Homeland (Mavi Vatan in Turkish), which aims to secure control of maritime areas surrounding its coasts.

Turkish drilling ship Yavuz seen last year being escorted by a Turkish naval vessel to the Cyprus coast

But apart from territorial waters, there are exclusive economic zones (EEZs) in place, like that agreed between Turkey and Libya, but also like the Cypriot EEZ accords with Lebanon, Egypt and Israel.

And this latest row also involves continental shelves, which can stretch up to 200 miles from the shore.

Greece argues that the Turkish survey ship that set sail from Antalya is encroaching on its continental shelf, pointing to a large area off the Greek island of Kastellorizo, 2km from the Turkish mainland.

While Athens has called on Turkey to leave its continental shelf immediately, Turkey insisted last month that "islands that are far from the mainland and closer to Turkey cannot have a continental shelf".

Turkey's vice-president said last month that Ankara was tearing up maps "drawn to imprison us on the mainland", and Ankara insists it is acting within the UN's Law of the Sea.

For more than 40 years Cyprus has been a divided island

- Published16 December 2019

- Published8 August 2019