Did Sweden's coronavirus strategy succeed or fail?

- Published

Brightly coloured beach towels line the shores of Lake Storsjon, two hours north of Stockholm.

Staycations are popular here this summer, thanks to a slew of travel restrictions imposed on Sweden by other countries, due to its coronavirus infection rate.

More than 5,500 people have died with Covid-19 in this country of just 10 million. It is one of the highest death rates relative to population size in Europe, and by far the worst among the Nordic nations. Unlike Sweden, the rest all chose to lock down early in the pandemic.

"Maybe we should have taken some more care of each other," says Dan Eklund, 31, visiting the lake on his friend's boat.

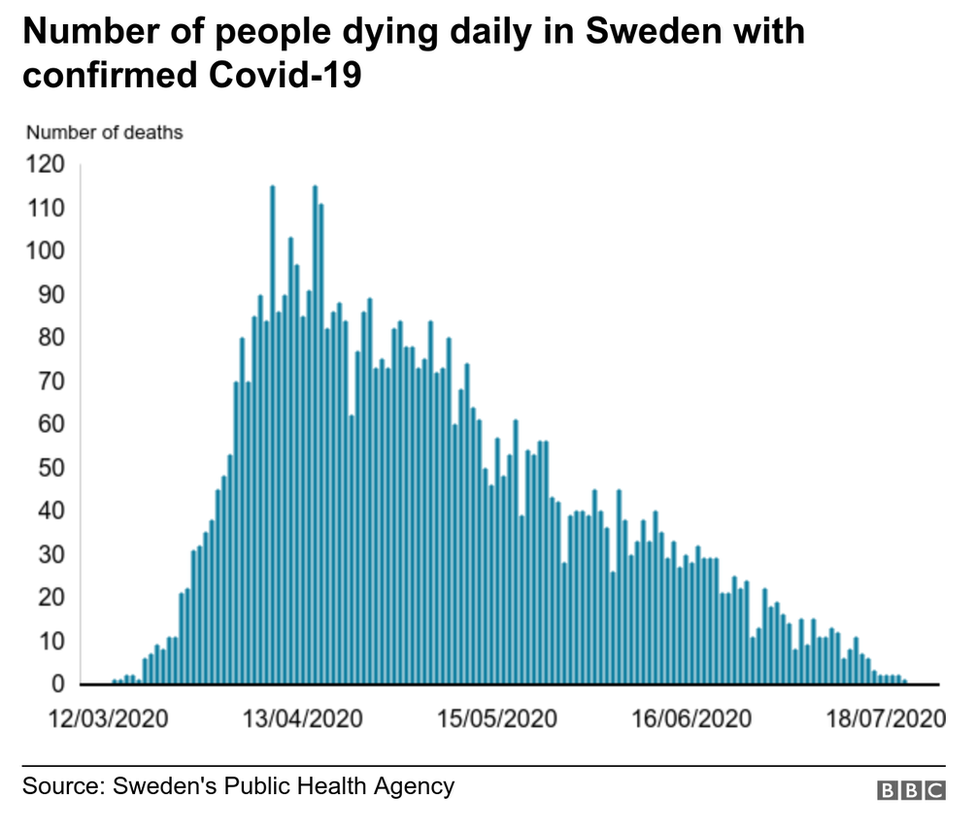

Latest figures suggest Sweden is getting better at containing the virus. The number of daily reported deaths has been in single digits for much of July, in contrast with the peak of the pandemic in April, when more than 100 fatalities were logged on several dates.

There has also been a marked fall in serious cases, with new intensive care admissions dropping to fewer than a handful each day. Though still not as low as elsewhere in Scandinavia, it's a clear improvement.

"It feels good. I mean, finally, we are where we hoped we would be much earlier on," says Anders Tegnell, the state epidemiologist leading the strategy. He's admitted too many have died, especially in Swedish care homes. But he believes there is still "no strong evidence that a lockdown would have made that much of a difference".

What was Sweden's strategy?

Sweden has largely relied on voluntary social distancing guidelines since the start of the pandemic, including working from home where possible and avoiding public transport.

There's also been a ban on gatherings of more than 50 people, restrictions on visiting care homes, and a shift to table-only service in bars and restaurants. The government has repeatedly described the pandemic as "a marathon not a sprint", arguing that its measures are designed to last in the long term.

Dan Eklund (R) says "maybe we should have taken some more care of each other"

The unusual strategy has attracted global criticism, with even some of Dr Tegnell's early supporters saying they now regret the approach. Annika Linde, who did his job between 2005 and 2013, recently told Sweden's biggest daily newspaper Dagens Nyheter she believed tougher restrictions at the start of the pandemic could have saved lives.

But according to clinical epidemiologist Helena Nordenstedt, there's no consensus in Sweden's scientific community that the strategy as a whole has failed.

The strategy was to flatten the curve, not overwhelm health care capacity. That seems to have worked. If you take care homes out of the equation, things actually look much brighter

Are Swedes better at social distancing?

Anders Tegnell says his modelling indicates that, on average, Swedes have around 30% of the social interactions they did prior to the pandemic.

And a survey released this week by Sweden's Civil Contingencies Agency suggests 87% of the population are continuing to follow social distancing recommendations to the same extent as they were one or two weeks earlier, up from 82% a month ago.

Restaurant manager Shiar Ali says not everyone is adhering to social distancing guidelines

Nordenstedt believes since Swedes have had longer to adjust how they act in public than countries that went into lockdown, this could help Sweden to mitigate a potential second wave.

"People are not as exhausted as they might be in other countries where the restrictions have been much wider and much stricter."

But while Swedes are aware of the guidelines, there have been reports of large gatherings and mingling in some tourist hotspots since domestic travel restrictions were relaxed last month.

"We try to tell them and show them to keep their distance," says Shiar Ali, a manager at one of the beachfront restaurants on Lake Storsjorn. "Especially young men and young people, they don't care about it."

Has Sweden achieved herd immunity?

Sweden's authorities never said achieving herd immunity was their goal, but they did argue that by keeping more of society open, Swedes would be more likely to develop a resistance to Covid-19.

Five months into Europe's pandemic and only 6% of the population here is known to have antibodies, according to Swedish Public Health Agency research.

However, Anders Tegnell believes the true figure is "definitely a lot higher", as immunity "has proven to be surprisingly difficult to measure".

Eva Britt Landin (right) backs Sweden's approach "because nobody knows exactly how we should do it"

The state epidemiologist points to recent research by the Karolinska Institute that found even people testing negative for coronavirus antibodies had specific T-cells which can provide immunity by identifying and destroying infected cells.

But other Swedish scientists are more cautious about predicting resistance to the virus. "I think he is overconfident," says Helena Nordenstedt. "We can all hope it will have an effect on the infection case numbers in Sweden during the fall, but we don't know yet."

How's the Swedish economy doing?

The strategy was not designed to protect the economy either, but the government argued keeping more of society open could limit job losses and mitigate the impact on business.

Research from Scandinavian bank SEB in April suggested Swedes were spending at a higher rate than consumers in neighbouring Nordic nations.

Despite this, various forecasts predict the Swedish economy will still shrink by about 5% this year. That's less than other countries hit hard by Covid-19 such as Italy, Spain and the UK, but still similar to the rest of Scandinavia. Sweden's unemployment rate of 9% remains the highest in the Nordics, up from 7.1% in March.

Though more businesses stayed open than in other countries, forecasts predict the Swedish economy will still shrink by about 5% this year

"Sweden, like the other Nordic countries, is a small, open economy, very dependent on trade. So the Swedish economy tends to do poorly when the rest of the world is doing poorly," explains Prof Karolina Ekholm, a former Deputy Governor of Sweden's central bank.

Restaurants, shops and gyms have been allowed to remain open, but they have still struggled to attract customers, she says.

But she does believe the right call was made to keep schools open for under-16s.

There's been less disruption for the generation now growing up - in terms of learning. That may produce benefits further down the line when [they start] entering the labour force

A blow for Sweden's image

In the short term, Sweden's Covid strategy is affecting its usually close relationship with its neighbours.

Norway, Denmark and Finland opened their borders to one another in June, but excluded Sweden due to its high infection rate, although Swedes from less affected regions have since been given more freedom to visit Denmark.

A YouGov survey last month found that 71% of Norwegians and 61% of Danes were concerned about keeping Swedish tourists away, a higher number than for visitors from countries like Spain, Italy and the UK.

"I don't think this will affect the relations in the longer term," says Helen Lindberg, a senior lecturer in government at Uppsala University. "But it has highlighted or brought back old grievances between our countries."

A bigger problem could be the impact on Sweden's wider international reputation for high-quality state health and elderly care, she believes. "There has been a blow to the Swedish image of being this humanitarian superpower in the world. Our halo has been knocked down, and we have a lot to prove now."

How national support weakened

At the start of the pandemic, there was a consensus that Sweden's state scientists should be trusted to guide political decisions.

But debates sharpened as the death toll increased, especially in care homes, and Prime Minister Stefan Lofven recently announced a coronavirus commission to look into the response from authorities at a national, regional and local level.

Helen Lindberg believes the strategy has called into question a historic reliance on public agencies to inform policies and highlighted a lack of preparedness for crises. "It's a perfect storm for our weak, minority government," she says.

When it comes to the pandemic, polls suggest Swedes have more confidence in the Public Health Agency than in their government

Just 45% of Swedes now have confidence in the government's ability to handle the pandemic, according to a Novus survey last month, down from 63% in April.

Confidence in the Public Health Agency has also dipped, but remains at a much higher 65%, compared with 73% at the peak of the pandemic.

"We believe they have the right strategy, because nobody knows exactly how we should do it," says holidaymaker Eva Britt Landin, 66, who's having a socially-distanced lunch with her 102-year-old father at Lake Storsjorn,

But Catherina Eriksson, 42, who's visiting from Stockholm, says the jury is still out. "We don't know what things will look like in the autumn or next year. We'll just have to wait and see."

GLOBAL SPREAD: Tracking the pandemic

FACE MASKS: When should you wear one?

VACCINE: How close are we to finding one?

- Published8 June 2020

- Published3 June 2020

- Published19 May 2020

- Published25 April 2020

- Published24 April 2020

- Published29 March 2020