Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko under fire

- Published

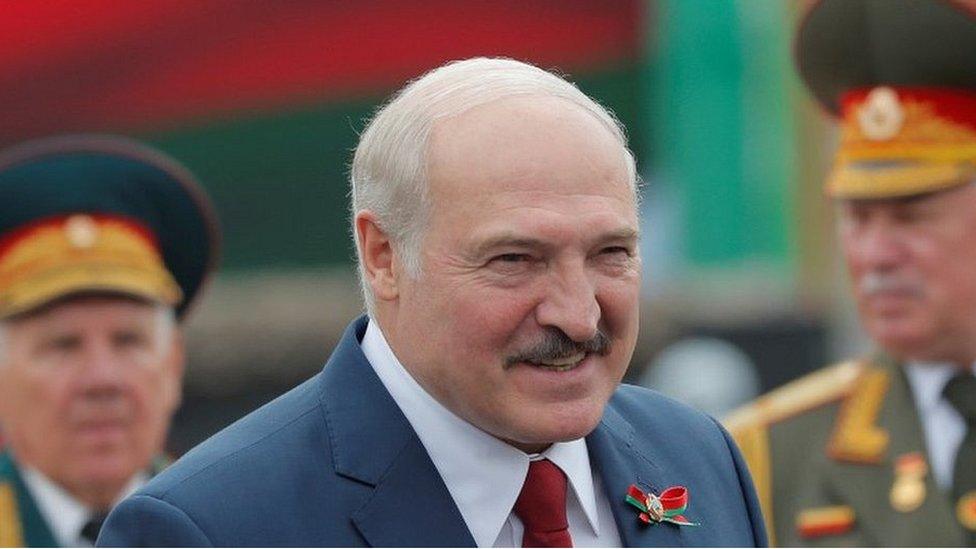

Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko, Europe's longest-serving ruler, is facing unprecedented opposition to his power.

The 66-year-old former Soviet farm boss claimed a sixth term as president in a widely disputed election on 9 August. He has faced weeks of mass protests against his rule.

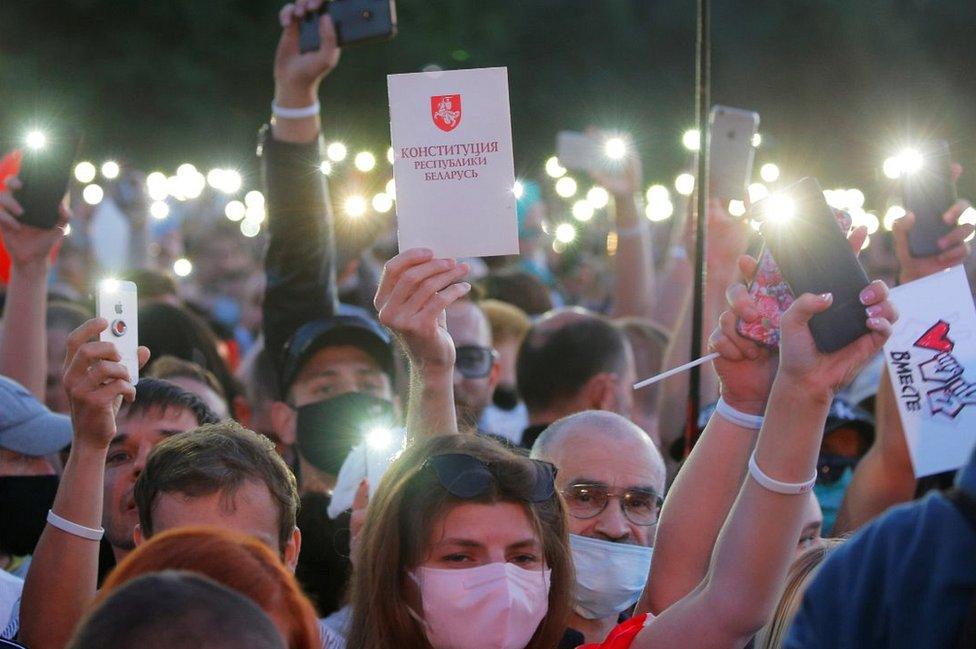

About 100,000 people have rallied against him weekly in Minsk - by far the biggest opposition protests of his rule.

Mr Lukashenko has been in power since 1994, with an authoritarian style reminiscent of the Soviet era, controlling the main media channels, harassing and jailing political opponents and marginalising independent voices.

The country's powerful secret police - still called the KGB - closely monitors dissidents.

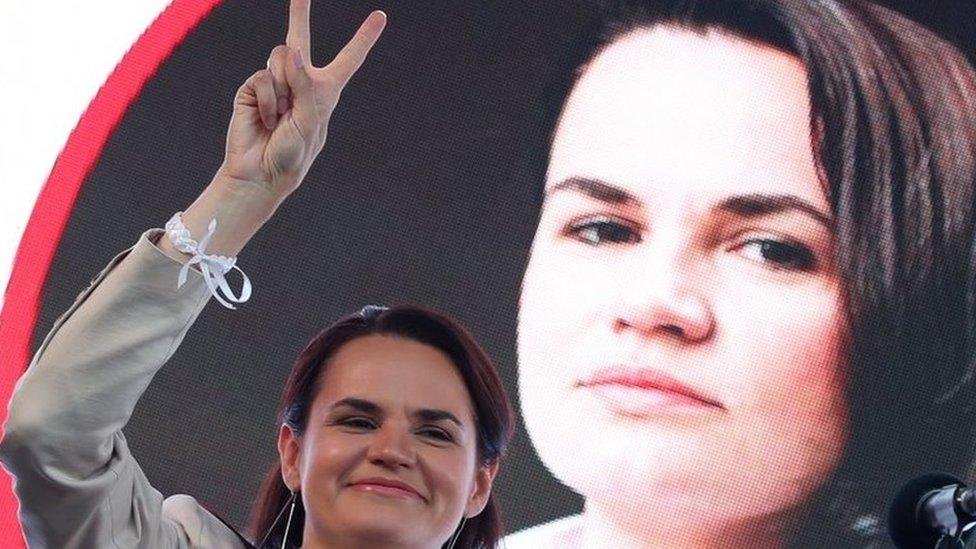

Political novice Svetlana Tikhanovskaya is now Mr Lukashenko's main political rival. She stepped in to challenge him for the presidency after her husband Sergei Tikhanovsky, a popular blogger, was barred from running and sent to jail.

On 30 July a huge crowd rallied in support of Svetlana Tikhanovskaya

She claims to have won 60-70% in places where votes were properly counted - but the president claimed a landslide victory.

None of the previous presidential elections held during Mr Lukashenko's long reign were ever judged free and fair by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), a top election monitoring body.

But the latest vote, and subsequent crackdown with thousands arrested, has sparked the widest condemnation yet.

Major opposition figures, including Ms Tikhanovskaya, are now in exile in neighbouring countries, amid a wave of arrests.

Scars of war

For years Mr Lukashenko has sought to convince the nation of 9.5 million that he is the best guarantor of stability, a tough nationalist protecting them from foreign meddling.

That message still appeals to many older Belarusians. The country was devastated in World War Two - victim of a Nazi scorched-earth policy - and lost nearly one-third of its population. So suspicion of foreigners and pride in the security forces play well among many voters.

Back in 2005 the administration of then US President George W Bush called Belarus "the last remaining true dictatorship in the heart of Europe".

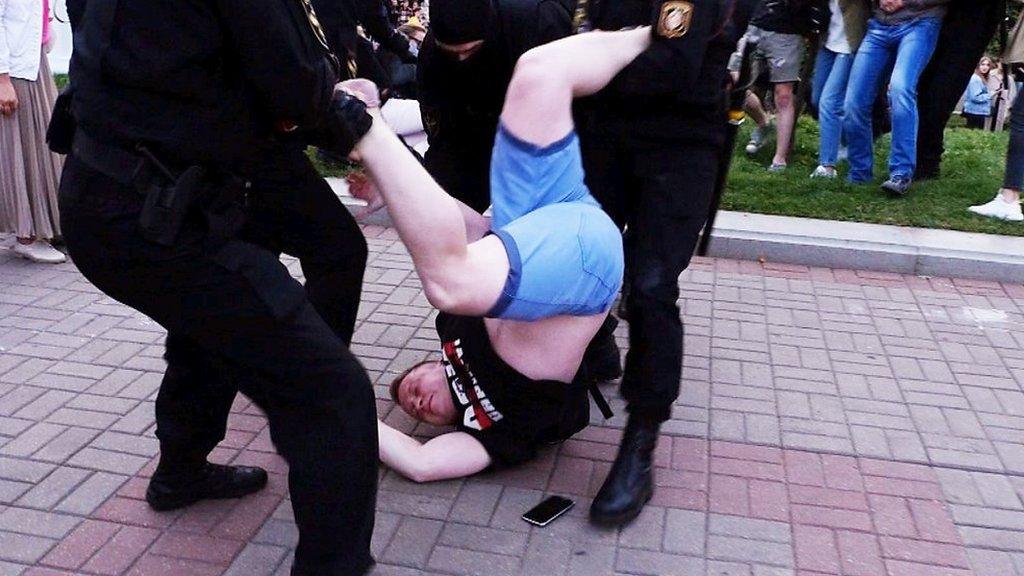

Mr Lukashenko once warned that anyone joining an opposition protest would be treated as a "terrorist", adding: "We will wring their necks, as one might a duck".

Activists and journalists were rounded up and jailed in Belarus before the election

In recent years, however, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Hungary's Prime Minister Viktor Orban have also drawn strong Western criticism for harassing opponents and extending state power.

Fearless of Covid-19

Coronavirus has added an extra dimension to the political ferment in Belarus.

Opponents consider Mr Lukashenko's bravado about the virus to be reckless and a sign that he is out of touch.

In late May he said Belarus was right not to lock down. "You see that in the affluent West, unemployment is out of control. People are banging on pots. People want to eat. Thank God, we avoided this. We didn't shut down."

In March, as countries across Europe were imposing lockdowns, he said: "I am convinced that we may suffer more from panic than from the virus". He suggested combating the virus with hard work, the sauna and vodka.

When the rest of Europe cancelled football matches the continuing Belarus fixtures - still drawing big crowds to stadiums - suddenly attracted international interest.

In February Mr Lukashenko (C) played against Mr Putin (L) in a friendly ice hockey match in Sochi, Russia

Tensions with Russia

Before the election Mr Lukashenko's security chiefs accused unnamed Russian forces of trying to help his opponents and foment unrest.

Russia remains Belarus's chief ally - they have held joint military exercises and the struggling Belarus economy relies on trade with its powerful neighbour.

But in recent years relations have cooled since Moscow moved to end subsidised oil and gas supplies.

Belarus authorities arrested 33 Russians near Minsk - all but one at a sanatorium - in July and said they belonged to Wagner, a shadowy Russian mercenary group active in Ukraine, Africa and the Middle East.

Russia denied the Belarusian claim that the detained Russians were plotting acts of terrorism, insisting that they were actually in transit, waiting for a flight to Istanbul. They were later released.

A former Soviet state farm director, Mr Lukashenko became president in 1994 after leading an anti-corruption drive in parliament.

In the August 1991 botched coup attempt against then Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, Mr Lukashenko supported the communist hardliners.

Like Vladimir Putin, Mr Lukashenko remains nostalgic for the Soviet Union. And both are keen ice hockey players.

A rare audience with Belarus' President Alexander Lukashenko

A referendum in 2004 lifted the two-term limit on presidents, making it possible for Mr Lukashenko to lead Belarus indefinitely.

His origins were humble - raised by a single mother in a poor village in eastern Belarus.

He is married to Galina Lukashenko, with whom he has two adult sons, Viktor and Dmitry. He told an interviewer in 2015 that he had no intention of divorcing Galina, although they have not lived together for decades.

He has a third son, Nikolai, born in 2004, whose mother Irina Abelskaya was Mr Lukashenko's personal doctor.

"An authoritarian style of rule is characteristic of me, and I have always admitted it," he said in August 2003. "You need to control the country, and the main thing is not to ruin people's lives."

Despite the mass unrest, Mr Lukashenko insists he will not leave office - but has acknowledged some Belarusians might be "fed up" with his rule.

He said Belarus could not return to the instability of the years following the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991, and he has twice appeared brandishing a gun during the protests.

President Putin says he has formed a police reserve force to intervene in Belarus if necessary - as requested by Mr Lukashenko. Russia could send them in if the protests got really "out of control", Mr Putin said.

- Published1 August 2020

- Published9 May 2020

- Published14 July 2020

- Published1 October 2015

- Published22 October 2012

- Published22 July 2020