Child abuse: The Irish victims still battling the state

- Published

John Boland with some of his classmates in the late 1960s

John Boland was 45 years old, married with grown up children, when a "dark secret" he had kept for almost four decades was suddenly exposed.

His name had been found on a 1960s attendance register from a school where many young boys were abused on a daily basis by their teenage teacher.

John was among 19 known victims at Creagh Lane school in Limerick.

But he had told no-one of the abuse he suffered, not even his wife, until Gardaí (Irish police) contacted him out of the blue, asking for a statement.

John says his wife was "shocked" by the revelation.

"We went though a terrible time," he says, recalling how he had to tell his family he was regularly molested between the ages of six and seven.

Now in his 60s, John Boland (centre) chairs a support group for child abuse survivors

"It was the same method of operation that you've probably heard many times before," John explains.

"You'd be called up to the front of the class for some reason or another, the teacher would put his cloak around you and start interfering with you."

They never knew who would be chosen, and John spent a full school year hoping to "get through the day without being molested".

The old Creagh Lane school building still stands on Bridge Street in Limerick

John and other former Creagh Lane boys eventually took their abuser to court, where he admitted indecently assaulting 19 pupils.

Seán John Drummond, from Ballinteer in Dublin, pleaded guilty to 36 charges and was sentenced to two years in prison in 2009.

More than a decade later, John and his schoolmates are still fighting for state compensation.

John Boland pictured outside the Irish parliament with some of his fellow campaigners

Day school pupils lived at home with their families - as such they did not qualify for the same compensation offered to victims abused in residential institutions.

The Irish state has already paid substantial sums to thousands of people abused as children, spending over €1.1bn (£996m) on a Residential Institutions Redress Board, external.

But unless you lived in the place you were abused, you could not apply.

John asks: "What difference does it make which room you were abused in?

"Yes, we went home every day to our parents, but you knew you had to face it again the following morning."

Long-term trauma

John is now a member of a group seeking redress and they have taken their campaign to the Irish and European Parliaments.

John Boland at the European Parliament with some of the politicians who organised the visit

It is not simply about money he argues - childhood abuse had a traumatic effect on many victims, with some struggling with severe mental health problems.

Two of John's classmates died by suicide and others have attempted suicide.

John says they were "locked out" from a support service for residential abuse survivors, external, which included counselling and psychiatric services.

Landmark judgement

Successive Irish governments spent years defending day schools compensation claims, arguing the state was not responsible for what happened in institutions it neither owned nor managed.

Although national schools (Irish primary schools) were state-funded, they were owned by religious denominations, mainly the Catholic Church.

Several day school victims dropped state compensation claims, fearing financial ruin after government warnings it would pursue them for legal costs.

But one woman was prepared to risk it.

Louise O'Keeffe was one of 21 girls abused by Leo Hickey, former principal of Dunderrow National School in County Cork, who was jailed for indecent assault in 1998.

After his conviction, Ms O'Keeffe fought a 15-year battle to hold the state liable for the abuse she suffered when she was eight.

She lost her case at Ireland's High Court, and the Supreme Court, and at one stage faced losing her home as legal costs reached hundreds of thousands of euros.

But she persevered, taking her case to the European Court of Human Rights.

In 2014, she won a landmark judgement which ruled the state failed in its duty to protect her from the abuse she suffered as a schoolgirl.

Louise O'Keeffe now campaigns on behalf of other child abuse victims in the same position

The O'Keeffe v Ireland ruling, external caused major embarrassment and prompted an apology from the then Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) Enda Kenny.

At the time, broadcaster RTÉ said the ruling had implications for about 350 victims.

The following year, the government launched an ex gratia (out of court) compensation scheme, external for victims with claims similar to Ms O'Keeffe's, but who had already dropped legal challenges.

'Blocking mechanisms'

However, the rules stated there had to be a "prior complaint of sexual abuse" to school authorities.

This meant many victims were immediately excluded, including the Creagh Lane boys.

The teacher who abused them was in his late teens when he began working at Creagh Lane - John Boland asks how could they have produced evidence of a prior complaint against a first-time teacher.

Their abuser confessed and was convicted, but John says even that "wasn't good enough for the state".

He believes the rules were "blocking mechanisms" to prevent compensation claims.

Further apology

So few claims succeeded under the scheme that a retired judge was appointed to re-assess rejected cases.

Mr Justice Iarfhlaith O'Neill criticised the prior complaint rule, concluding it was "incompatible" with the O'Keeffe judgement.

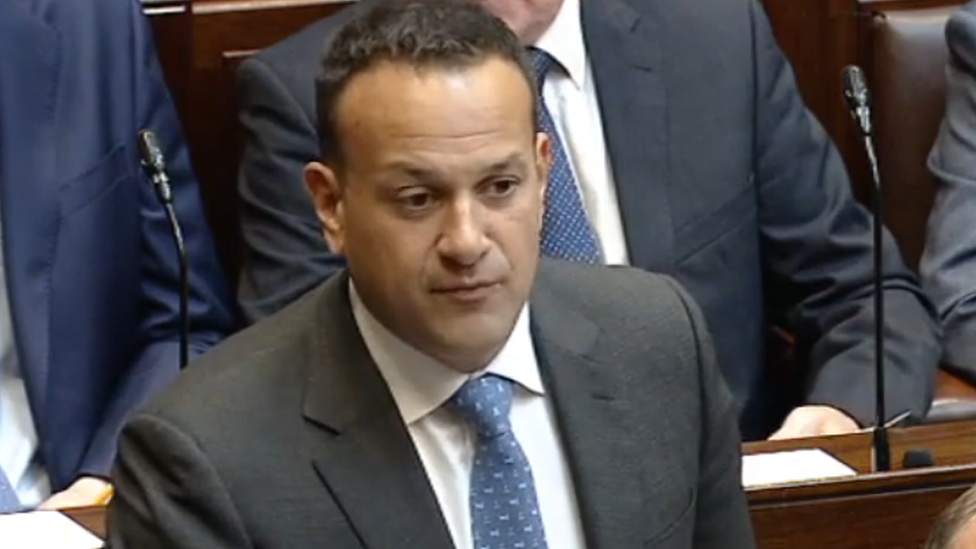

Following the publication of the ex-judge's review in July 2019, the then Taoiseach (Irish prime minister) Leo Varadkar apologised to all day schools abuse victims.

Leo Varadkar apologised to victims following criticism of ex gratia scheme rules in July 2019

He said the government would consider the possible re-opening of the ex gratia scheme, but needed "time to get that right".

The then leader of the opposition Micheál Martin accused the government of "cruelness" towards victims.

'We're living in hope'

Since then, there has been a global health emergency; a change of government and Micheál Martin is now taoiseach.

But day schools survivors are still waiting for redress.

The Irish Department of Education confirmed that to date, 16 payment offers have been made under the ex-gratia scheme, 15 of which have been accepted.

But it still has not completed a review, following criticism of its eligibility rules.

Micheál Martin came to power in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic

Almost seven years after her own victory, Louise O'Keeffe is "extremely frustrated and so disappointed" by the lack of progress for other victims.

"Words mean nothing," she says, insisting government apologies must be followed by action.

"It is so, so wrong to treat people who have been sexually abused as children like this."

John Boland is confident the new taoiseach, Mr Martin will help, given his previous support for their campaign.

"We do believe he will sort this out," John says. "We're living in hope."

- Published28 January 2014