Brexit: Why France is raising the stakes over fishing

- Published

France has so far refused to consider any change to existing fishing arrangements

In a cramped cabin, with the green waters of the Channel bobbing and tipping outside, Laurent Merlin listens to messages from Dutch and Belgian fishermen crackling over the radio.

Sharing their positions helps avoid any clashes - a technique that works better at sea than at summits.

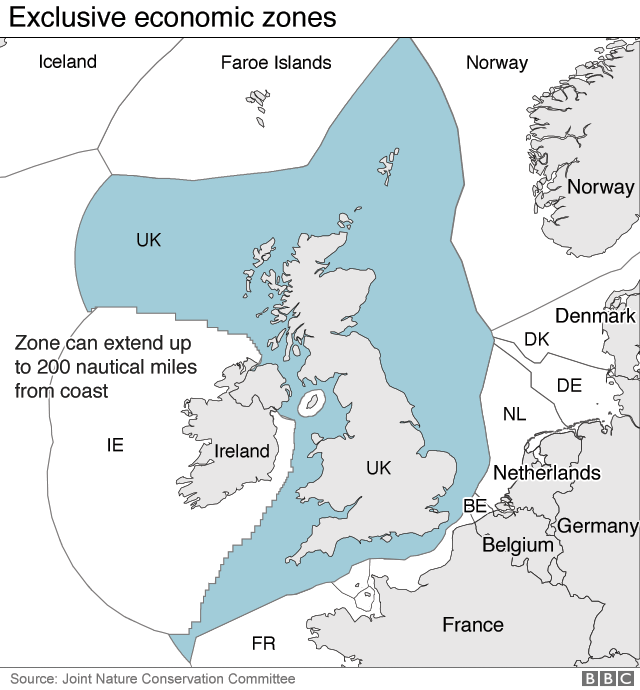

With less than three months to go until Britain leaves the EU single market, fishing has become a key sticking point in negotiating a trade deal to replace it. Especially when it comes to access for EU fishermen in UK waters.

European leaders are due to meet on Thursday to try to find a way forward.

Most of the crabs and lobsters caught by this French boat come from UK waters

Laurent Merlin is based in Boulogne-sur-Mer, a city at the heart of France's fishing industry.

His grandfather used to fish in the waters off Scotland, while his father fished in the Channel.

'We might decide to flex our muscles'

Today, three-quarters of Laurent's own crabs and lobsters come from British fishing grounds. He's worried that the ebb and flow of post-Brexit trade negotiations could sink boats like his if they're denied access.

"If we can't enter British waters, it's practically the end of our profession," he said.

"We might decide to flex our muscles. We got into trouble before for blocking the port of Calais, but it's something we'll discuss

A quarter of France's national catch comes from Britain's fish-rich waters. In northern ports like Boulogne-sur-Mer, fishermen are dependent on them.

"If there's no deal, we're going to ask that the French get the French waters," Mr Merlin explained. "That the Belgians go back to Belgium, and the Dutch as well. Because if all those boats get kicked out and come here [to French fishing grounds], it'll be unbearable."

The UK is said to have suggested changing the way its fish stocks are allocated, and tapering off EU catches there over three years.

'Fishermen are for no deal'

France has so far refused any change to the current arrangements, saying it won't abandon its fishermen. "No deal is better than a bad deal," the government says.

Annaïg Le Meur is a Brittany MP from President Emmanuel Macron's party. "I think the fishermen are for no deal," she told me. "They are afraid, and when people are afraid they choose either yes or no, not the solutions in between."

But talk to fishermen in Boulogne, and many say they would accept a compromise on their British quotas, rather than lose access completely.

Stéphane Pinto, the deputy head of the regional fishing committee in Boulogne, told me: "It would be a lot more acceptable to have 80% of the catch in British waters than nothing at all."

What about 60% of the catch?

"Errrr…. that's not viable," he said. "But with some sort of financial compensation? Maybe."

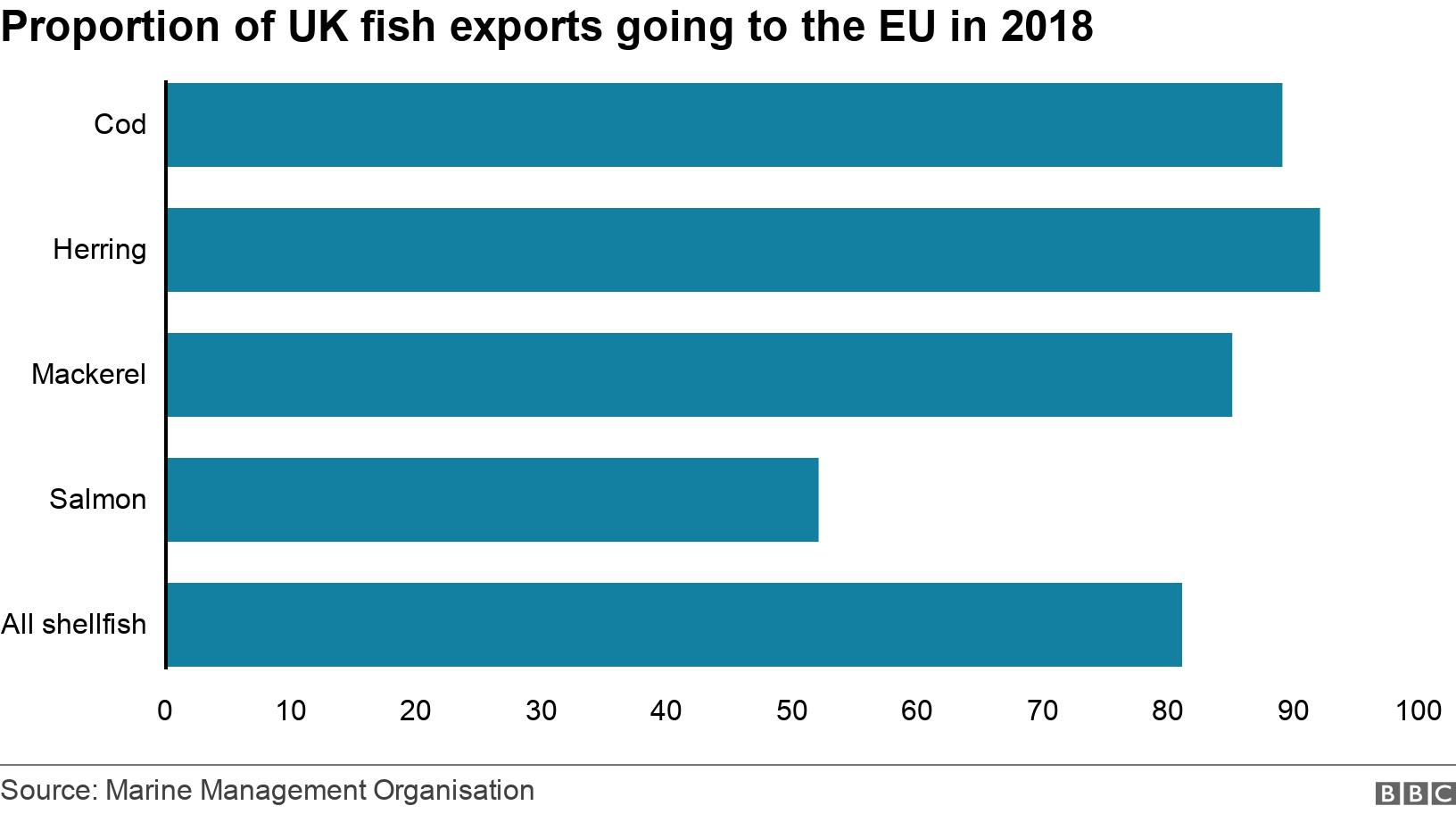

Three-quarters of Britain's catch is sold to the EU

The EU's chief negotiator has pleaded with leaders for some wriggle room on fishing that would allow the two sides to find a compromise.

Why Macron appears hard line

France has said it will not consider fishing separately from the rest of the deal. A source at the Elysée Palace said the country would not negotiate over fishing rights "like carpet merchants" without assessing the overall package.

Some fishermen fear they will be sacrificed for British agreement on other key issues, like state aid.

And with new British legislation allowing the UK to break part of its withdrawal agreement with the EU, trust is in short supply.

"We do want to trust the UK," Clément Beaune, France's Europe minister said. "[But] what we have seen in the last weeks regarding the withdrawal agreement is extremely worrying. There will be no agreement on future relations if we don't have full confidence on respect of the withdrawal agreement."

Despite the French government's tough line, many here believe a deal on fishing is possible. So why does President Emmanuel Macron seem more hard line than the fishermen themselves?

Journalist John Lichfield has covered the EU fishing industry, from France and Brussels, for more than 30 years. He says there are high political stakes for Mr Macron in the northern part of France.

"The north of France around Boulogne is hugely important for the presidential election in 2022," he says. "The regional president... might well be one of Macron's main rivals at that time, so he [Macron] needs to be seen to be supporting what is already a struggling area economically."

But Mr Macron is not the only one facing pressures.

"What is going to be more difficult is [UK PM] Boris Johnson turning on its head some of the exaggerated rhetoric there's been around fishing and Brexit in the British imagination, and certainly in the Conservative imagination, in the past two or three years," says Mr Lichfield.

"And so it's probably harder for Boris Johnson to make that deal [on fishing] than it is for Macron."

But it's not just EU industries that could lose out if there's no deal on fishing.

At Boulogne's fish market, buyers are up before dawn to choose fish for their restaurant tables. Three quarters of Britain's catch is sold to the EU.

A no-deal risks a kind of mutually assured destruction for fishermen on both sides of the Channel.

But navigating contested waters like these is much harder for negotiators in Brussels than fishermen in Boulogne.

- Published23 December 2021

- Published1 January 2021

- Published26 January 2024