The young Norwegians taking their own country to court over oil

- Published

A young environmentalist in the Barents Sea at night time

Despite Norway's green credentials, its state wealth is due to its huge oil exports. This week, Norwegian youths are challenging what they describe as a double standard, in court.

In the Barents Sea in June, the sun is still shining at 2am.

Small waves refract the orange sunlight into the hazy air. A sailing boat cuts through the freezing Arctic waters. Far beyond it, on the horizon, rises a giant. This is Goliat, the world's northernmost operating oil rig, drilling for fuel on the Norwegian continental shelf.

The boat's radio crackles. Goliat's workers are warning the ship's crew to stay out of the rig's exclusion zone.

"And enjoy sailing," the rigger adds.

"And you guys," the 21-year-old captain, Thor Due, says, "enjoy drilling!"

Thor's natural politeness overrides his true feelings.

It is 2018, and Thor and his crewmates are on their way home from Bear Island, south of the Svalbard archipelago, where they have been documenting the area's rich wildlife. They worry this unique landscape would be threatened by any oil spills.

But their main concern is far bigger.

It is just a few months after Thor and other members of Norway's Nature and Youth group - environmentalists under the age of 25 - lost the first round of what has become a long-running legal fight with the Norwegian state over oil.

On 4 November, this battle will come to a head when the two sides face each other for a final hearing in Norway's Supreme Court.

Thor and his fellow activists want to set their country on a new course - to force one of the wealthiest states in the world to abandon its biggest source of income.

They say that oil and gas being extracted from Norwegian waters, to be sold on to the rest of the world, is contributing to devastating climate change. Norway is Europe's second-biggest oil producer after Russia.

The activists contend that by issuing new licences for oil exploration in the Arctic in May 2016, the state breached its own constitutional obligation to ensure a clean environment for its citizens and future generations.

The group, together with members of Greenpeace Norway, lost the initial case - the court ruling that Norway could not be held responsible for pollution beyond its borders.

Former leaders of Nature and Youth and Greenpeace Norway at the first court case in October 2017

They also lost a subsequent appeal, with the court still ruling that the state was not in contravention of its constitution, although it did this time agree that Norway should be held accountable for its foreign emissions.

But in Norway a court case can be appealed twice, hence the final debate in the Supreme Court.

Thor's early years were spent sailing with his father, zig-zagging across the North Sea to avoid the various rigs' exclusion zones - an experience that brought him up close to the industry he is now taking on.

Thor Due on the Bear Island trip

Oil is a sensitive subject in Norway. The petroleum industry, majority-owned by the state, is credited with transforming the country from a poor fishing nation to the owner of the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world. If all its citizens stopped working, they could live off the oil money for three years.

Norway's oil production is estimated to account for approximately 0.7% of global emissions from fossil fuels, making the country the source of roughly 100 times the greenhouse gas emissions per capita of the world average.

And yet Norway has impressive green credentials in other ways. It was the first industrialised nation to ratify the Paris climate change agreement, which pledges to try and limit global temperatures to 1.5C above pre-industrial times. It is also a major donor to the Green Climate Fund, which finances environmental initiatives in developing countries, and has pledged that its oil fund money will never be invested in companies it judges particularly harmful to the environment.

Norway also has the highest per capita use of electrical cars of all countries in the world - 42,4% of cars sold in 2019 were electric., external

"The Norwegian paradox is that its leadership in some aspects of addressing the global climate emergency is enabled by wealth generated by a large petroleum industry," David Boyd, the United Nations' special rapporteur on the environment and human rights, said in a 2019 report, external.

Thor spent much of his early university life volunteering to help prepare for the two first court cases. Even though two more organisations eventually came on board, there were only a handful of paid staff - everything else was done by volunteers.

He and other members of Nature and Youth immersed themselves in the subject and became experts on marine oil and drilling.

Fellow Nature and Youth member Sigurd Toven Gautun

"It took six months before my parents realised that I wasn't actually studying," he says.

Thor grew up in the small town of Molde, where many people work directly or indirectly in oil.

"The best students were expected to become oil engineers," he says about his school days.

Emma Bugge Gjerdevik, a local leader for Nature and Youth, feels this pressure even more keenly. She is from Stavanger, which was a struggling fishing community until oil was discovered on the continental shelf nearby in 1969. It is now one of Norway's wealthiest towns, with the highest rate per capita of oil workers in the country.

"It is impossible not to know anyone who works in oil," the 17-year-old says of Stavanger, adding that this includes her own mother.

"The only sources of information you have when you are little are the school and your parents - who often work in the oil industry," she adds. "No-one said anything about the consequences of oil."

When she learned about climate change, Emma was scared. The only thing she could think to do, she says, was to become engaged in the issue.

"Many young people say: 'I can't be part of Nature and Youth, because my parents work in oil'," Emma says. "I try to explain to people that we must start exploring other supply and energy alternatives as well."

Emma and Thor are both frustrated about how adults react to their arguments. They get invited to meetings, they say, and are told how good it is that they take an interest, but feel the invites are only symbolic.

Emma Bugge Gjerdevik (R) debating with oil union leader Hilde-Marit Rysst (L) last year

"Adults often think that they know more [about the oil issue] just because they are older," Emma says. "But we have resources."

She remembers one oil manager she debated with, who accused her of making him "a villain". But she has come to view the real villain as the Norwegian state, which makes the decisions to extract petroleum.

"Oil is absolutely incredible," Emma says. "There is no other resource like it. It has contributed so much good. It is a safety net. So of course the older generations find it hard to think beyond it."

#Proud oil workers

The overall trend among Norway's public, who are regularly polled on their views about oil, is that just over half support the drilling.

"The petroleum industry has been one of the main engines of the Norwegian economy for more than 50 years," said Prime Minister Erna Solberg in a statement this spring. "If we lose the growth potential of this industry, we will also lose much of the momentum in Norway's transformation."

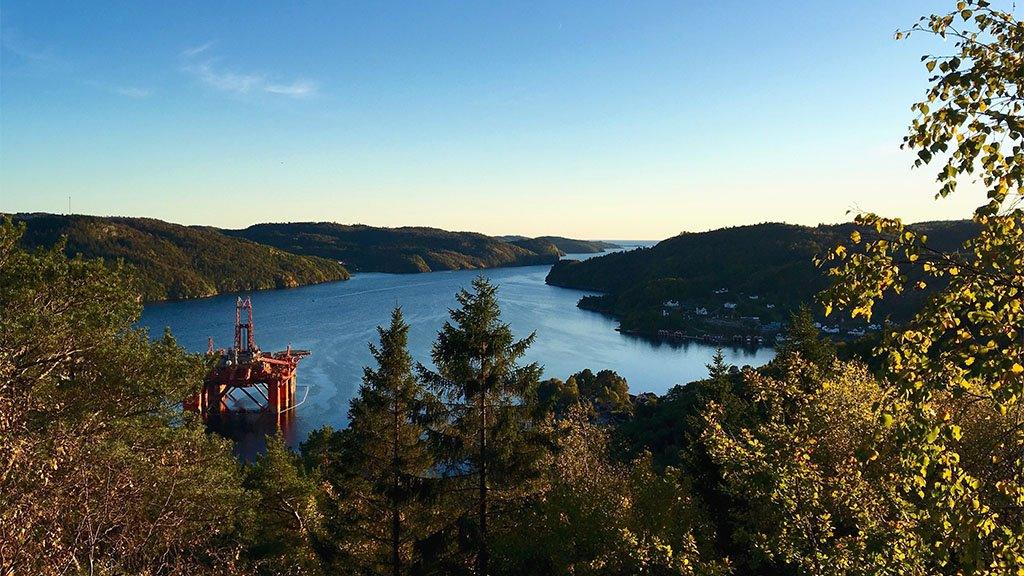

Finding oil was an economic game changer for Norway

But as climate change concerns have grown among the Norwegian population, the country's media has started writing about "oil shame".

In 2019, oil electrician Idar Martin Herland started the hashtag #stoltoljearbeider (#proud oil worker) to challenge this view.

"I saw that my colleagues felt exposed," he says. "But we produce something that the world needs." People criticise the oil workers, but that's unfair, he says.

"These same people drive [petrol] cars."

Green energy 'not ready'

Hilde-Marit Rysst, who used to work as an oil rig technician, and is now the leader of the labour union in which Idar Martin is active, stresses that oil workers care about the planet too, but people need to be realistic.

"The green energy isn't ready [to meet all our needs] yet," Hilde-Marit says. "For a long time to come, renewable energy will go hand in hand with fossil fuels."

"Young people are eager and impatient," Idar Martin adds. "But we really have to do this step by step."

And the Norwegian oil business is trying. Offshore drilling activities have been subject to a carbon tax since 1991, and by 2018, around 80% of greenhouse gas emissions were taxed. Norway is one of the world leaders in carbon capture, utilisation and storage.

"Norwegian oil is the greenest oil in the world - the best of the worst - and we invest the profits in the environment," Hilde-Marit says. "We can't get flak for that!"

She argues that as long as there is the demand for more energy, Norway is fulfilling a valuable role. Future generations will want cars and mobile phones too, she says.

But Thor and Emma believe it is possible to scale down consumption.

"In a post-oil Norway, we may not have the same economic progress, but it is much more important to me that I can breathe, have children with a clear conscience, than Norway being the richest country in the world," says Emma. "If not even the richest country in the world can start rebuilding, who will?"

Thor points out that Norway's neighbours have succeeded in creating flourishing societies without the economic benefits of "black gold".

"Sweden and Finland have managed to build a welfare state without oil," he says. "Still, we'll have to remove a little of our most luxurious and extravagant habits if we remove the oil; hold back a little."

Even if Emma and Thor don't win their case at the Supreme Court, they believe bringing this discussion to such a high profile stage is valuable.

Thor with other activists from Nature and Youth

Around 90 countries have constitutions similar to Norway's which explicitly recognise the right to a healthy environment. Thor and Emma hope that their case will set an international precedent.

And if they do win?

"It will be a game changer," says Thor. "It will show that Nature and Youth were right all along. They would have to listen to us."

All images subject to copyright