United Nations at 75 plagued by new crises and cash crunch

- Published

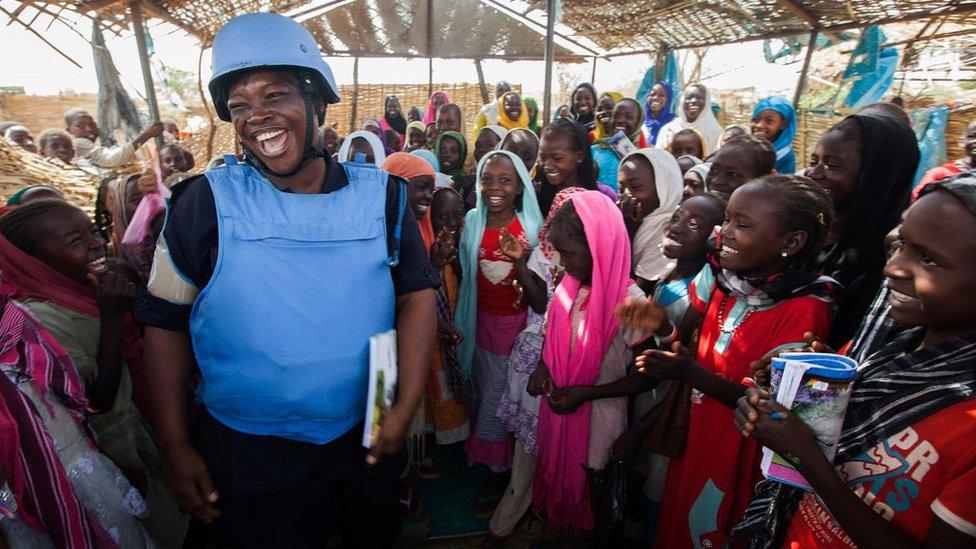

A Ghanaian UN policewoman with refugee children in Darfur, Sudan

The United Nations is 75. So are we celebrating?

It was born on 24 October 1945, out of the ashes of World War Two. Just 51 countries were there at the start, and many had only recently stopped fighting each other.

Today most of us have no memory of a time without the UN, so the decision to create a body to prevent conflict and address global challenges might seem obvious.

Back then, in a world dominated by nation states and fading empires, it was a radical move, says Mohamed Mahmoud Mohamedou, Professor of International Relations at Geneva's Graduate Institute.

"Seventy-five years ago the logic of setting up an international organisation like the United Nations was not necessarily obvious," he explains.

"The world was coming out of large-scale conflict, and the dynamics of multilateralism, the very concept of it, was not well known.

"But there was the realisation that this was the moment, if ever, to imagine a different type of world… that you have one place where all nations with one equal vote can come together and debate the questions of the world."

Multilateralism means countries working together to tackle shared challenges or crises, such as climate change or the current pandemic. It also means joint action in areas such as gender equality and universal education.

Those present at the UN's foundation invested huge hope in the new body. US President Harry S. Truman described it as "a victory against war itself… a solid structure upon which we can build a better world".

Britain's ambassador to Washington, Lord Halifax, told the assembled nations their approval of the new UN Charter was "as important [a decision] as any we shall ever vote in our lifetime".

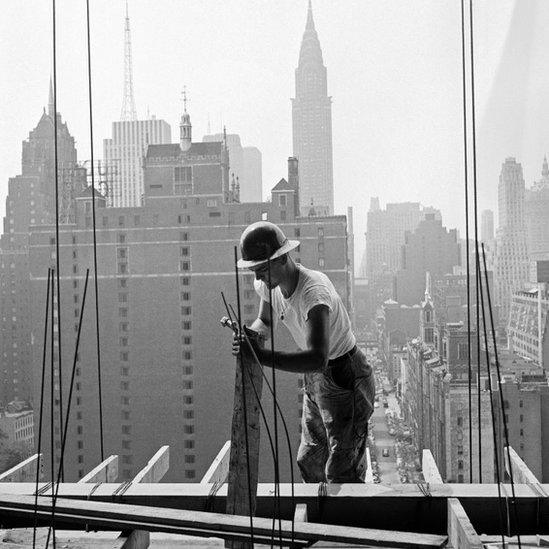

Construction of the UN HQ in New York in 1949

And now?

Fast forward 75 years and the world is facing precisely the type of challenge the UN was created to deal with: a pandemic. The World Health Organization, the UN's health body, should be perfectly placed to get us through Covid-19.

In fact, the WHO's efforts to tackle the pandemic have been marred by bitter criticism from one powerful member, the United States.

Washington claims the WHO failed to communicate the dangers of the disease quickly enough. The WHO disputes this, pointing out that it declared an international public health emergency way back in January.

But the US, unconvinced, has begun the process of leaving the WHO, taking millions of dollars in contributions with it.

That, taken together with the US withdrawal from the UN Human Rights Council, from the Paris Climate Accord, and its abandonment of the UN-backed Iran nuclear agreement, is an existential threat to the UN and multilateralism.

President Trump told the UN that national interests must come first

How can the UN respond? It will always be dependent on its 193 member states: for funding, as well as for political and moral support. There will always be tension with national governments uneasy at UN scrutiny, in particular by UN human rights teams.

Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein, former UN Human Rights Commissioner, believes timidity is the wrong response. The man who famously called Europe's populist leaders "demagogues", and suggested Donald Trump would be a dangerous president, thinks the UN needs to reassert its moral authority.

"The problem is that we have too much of the UN that seeks just to please governments," he says.

"Rather than the UN worry about how governments may react to UN statements, governments ought to worry about what the UN might be saying about them. It's a question of speaking with authority. Seventy-five years of experience in these fields - the UN needs to be reckoned with."

Read more about the UN:

The UN launched BCG vaccination against tuberculosis in Congo in 1962

Is reform needed?

The current UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, also acknowledges the inherent weakness of the UN.

This year he tried to get the UN Security Council to pass a resolution calling for a global ceasefire, to enable medical staff to cope unhindered with Covid-19. His efforts were stalled for months by the US, which objected to the WHO being mentioned, and by China, uneasy with the resolution's emphasis on "transparency".

"When we look at multilateral institutions, we have to recognise they have no teeth," said Mr Guterres wearily. "Or, when they do, they don't want to bite."

The structure of the UN contributes to that toothlessness. The five permanent members of the UN Security Council, the ones with a veto to block whatever they like, are the same as they were in 1945, the WW2 victors: the US, Russia (former USSR), France, China and the UK.

That is an astonishing state of affairs; the countries which emerged from colonial rule to gain their independence in the 1960s have never had that kind of power.

How much does America contribute to the UN's budget?

What's more, the system is not just outdated, it is regularly ineffective.

Syria is a prime example. For years the UN Security Council has failed to agree on a way to end the conflict, with the US and Russia regularly disagreeing, and Russia sometimes even vetoing vital measures like access for humanitarian aid.

But all attempts to reform the Security Council - Kofi Annan tried, Ban Ki-moon tried - have failed. Reform would have to be approved by the Security Council - an act akin to turkeys voting for Christmas.

What's the UN ever done for me?

It would be easy, given the paralysis over Syria, the disagreement with the WHO (not to mention the complaints of bureaucracy, and even of exploitation) to see the UN as well past its sell-by date.

And yet there are successes. Most of us, if we remember them at all, remember the 1990s as the decade of war in former Yugoslavia, and the Rwandan genocide - both events the UN, if it functioned perfectly, should have been able to prevent.

But Prof Mohamedou points out that the '90s were also the period when the UN pushed the world to set standards on big issues, with UN summits on racism, sustainable development, women, and human rights, culminating in the creation of the International Criminal Court in 1998.

"During those 10 years, you had a series of lead themes being addressed," he says. "That was a moment where I think the UN should be given credit for setting those standards."

US diplomat Stephanie Williams is trying to broker a Libya peace deal for the UN

Just this week, a low-key UN meeting in Geneva brought together Libya's warring factions and got them to agree a permanent ceasefire, a hugely important move for Libya's long-suffering civilians.

Earlier this month, the UN's World Food Programme was honoured with the Nobel Peace Prize, because of what the Nobel committee called "its efforts to combat hunger and its contribution to bettering conditions for peace in conflict-affected areas".

And in a nod to UN sceptics, the committee said pointedly "the need for international solidarity and multilateral co-operation is more conspicuous than ever".

In fact, there is little we care about these days, from climate change, to migration, to human rights, to gender equality, that the UN is not involved in. Not, its diplomats insist, to order us around, but to encourage us to work together for improvement.

It is easy to be cynical about this huge, unwieldy, rather worthy institution, but Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein, despite his concern over timidity, has confidence that the UN "with the brilliant people we have… can experience a revival and capture the imagination of people".

Or, as even sceptical US diplomats tend to admit, "If the UN didn't exist, we would have to invent it".

- Published26 September 2018

- Published9 October 2020

- Published5 September 2017

- Published7 April 2014

- Published30 May 2020

- Published9 July 2020

- Published15 September 2020

- Published4 September 2020

- Published22 September 2020