EU faces challenge from three states to Covid budget

- Published

There will be no bumping of elbows at this summit but Hungary's prime minister (R) is offering stiff resistance to the budget

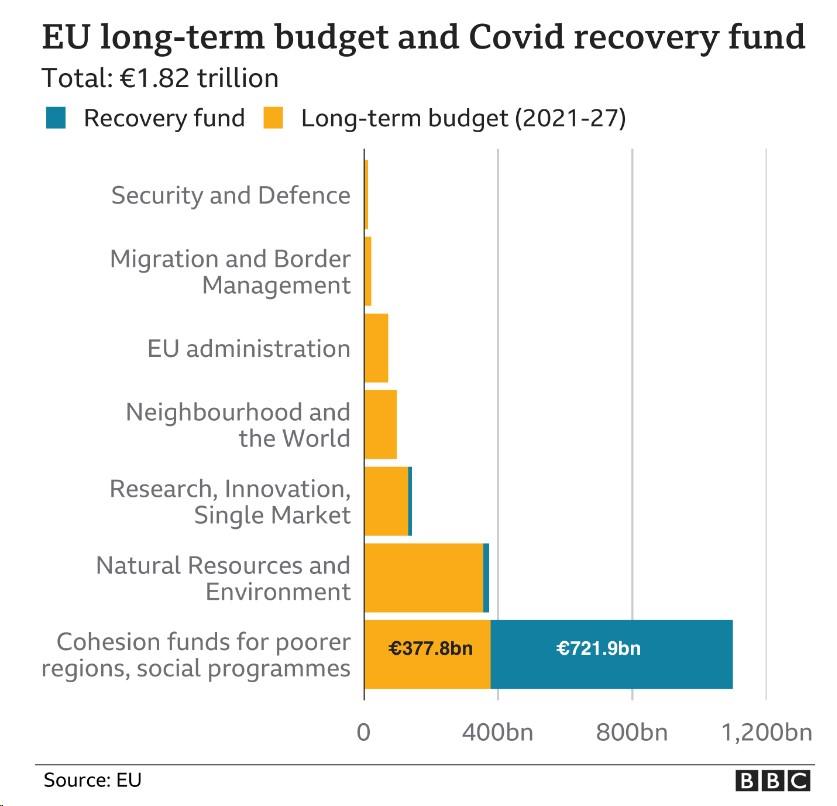

In Brussels a high-stakes game is being played in which the jackpot is worth €1.8tn (£1.6tn) - the total value of the EU budget until 2027 plus its €750bn Coronavirus Recovery fund.

On one side of the table sit 24 of the member states backed by the European Commission and a majority in the EU Parliament.

Facing them across the table are Hungary and Poland with Slovenia preparing to play a supporting role.

The issue for EU leaders meeting via video on Thursday is simple enough: should the division of EU funds between member states be linked to the behaviour and the values of individual governments?

Who is setting the rules?

The problem is that it's not quite clear what game they're playing - poker or chicken.

If it's poker then the two sides will play their cards carefully, winning some hands and losing others until some kind of compromise eventually emerges.

If it's chicken then they'll seek to wait each other out in the hope that the other side will lose its nerve first.

The EU wants to link the behaviour of member states with access to EU funds by means of a "rule of law" mechanism - in other words, pursue policies that the EU feels are in conflict with its core values and you lose access to EU funds.

European Council President Charles Michel, speaking in July, said the post-virus recovery package was a "pivotal moment"

Opposition to that idea comes from Poland and Hungary - with the support of Slovenia this time around.

Why Poland and Hungary?

The two larger EU states have a lot in common.

Both emerged as democracies from communist dictatorship as recently as the 1990s; both have gone on to elect right-wing nationalist governments and both are heavily dependent on EU funds.

They each receive around 5% of their GDP from Brussels. Many in the EU see their need for EU funds as a factor that will push them into backing down - but there's no sign of that happening yet.

And that uneasy combination of political opposition and economic reliance has introduced a strain of toxicity into their relations with Brussels.

Hungary Justice Minister Judit Varga accuses the EU of 'ideological blackmail'

Hungarian leader Viktor Orban - the man once greeted by Jean-Claude Juncker with a cheery cry of "Hello Dictator!" - sees it as a threat to his country's sovereignty.

He ties it to the long-running dispute between Brussels and those Eastern European states - like Hungary - which refused to help resettle migrants who cross the Mediterranean and end up as a burden on front-line states like Greece and Italy.

Once this proposal is adopted there'll be no more obstacles to tying member states' funding to support migration and using financial means to blackmail countries that oppose [it]

How far will Poland go?

Poland's nationalist-conservative coalition government says the rule of law mechanism breaches both EU treaties and the spirit of the agreement reached by leaders at a summit in July.

For hard-line justice minister Zbigniew Ziobro, who heads a junior coalition party, the mechanism is simply a pretext to erode Poland's sovereignty and force it to accept liberal policies such as same-sex marriage. One of his colleagues said it was an attempt by Germany to colonise Poland.

We say yes to the European Union, but no to being punished like children, no to mechanisms that mean Poland and other countries are treated unequally

The cover of government-supporting weekly magazine Sieci reads Veto or Death this week.

"The government is afraid this mechanism will create constant pressure on them and give Brussels and Berlin the ability to blackmail Poland. The definition of the rule of law is so broad the government thinks that in practice it means introducing a liberal-left agenda through this mechanism," its editor-in-chief Jacek Karnowski told the BBC.

There is a distinct lack of trust in Warsaw about Brussels' real intentions. Poland is currently the largest recipient of EU funds, but it's prepared to block the bloc's new budget, because it calculates it can wait for perhaps a year for a solution to be found, something it reckons many southern EU member states will not be able to do.

How far will it go? The depth of opposition within the government varies.

Foreign language-speaking Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki was picked for the job partly because of his ability to negotiate in Brussels. He is more moderate than Mr Ziobro and would perhaps be more willing to accept a compromise that more precisely defines the mechanism, allowing him to present it as a victory, both for Europe's and Poland's interests.

What hope of a compromise?

From the Brussels perspective, Poland and Hungary share rather more than similar recent histories.

Governments in other member states see worrying trends towards authoritarianism in both Warsaw and Budapest.

They're especially concerned by attempts to rein in or silence opposition voices in the media, and by judicial reforms which they see as naked attempts by governments to take greater control of the legal process.

Only on Wednesday a chamber of Poland's Supreme Court lifted the immunity of a judge who has been one of the most vocal critics of the governing coalition's reforms. The chamber was created by the coalition and the European Court of Justice has ordered its suspension, external.

We should be very clear. Now that taxpayers' money is being made use of to such an unprecedented extent, we should pay careful attention that our values are adhered to

One EU diplomat put it like this: "This is not about taking away the independence of any elected government - it's about having shared values and defending them."

The EU may take some comfort from the fact that the rotating six-month presidency is currently held by Germany, which places the search for compromise in the safe hands of Chancellor Angela Merkel.

But the search won't be easy.

Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte has already described the current proposals on a rule of law mechanism as a "bare minimum", when they are being rejected as excessive by Poland, Hungary and Slovenia.

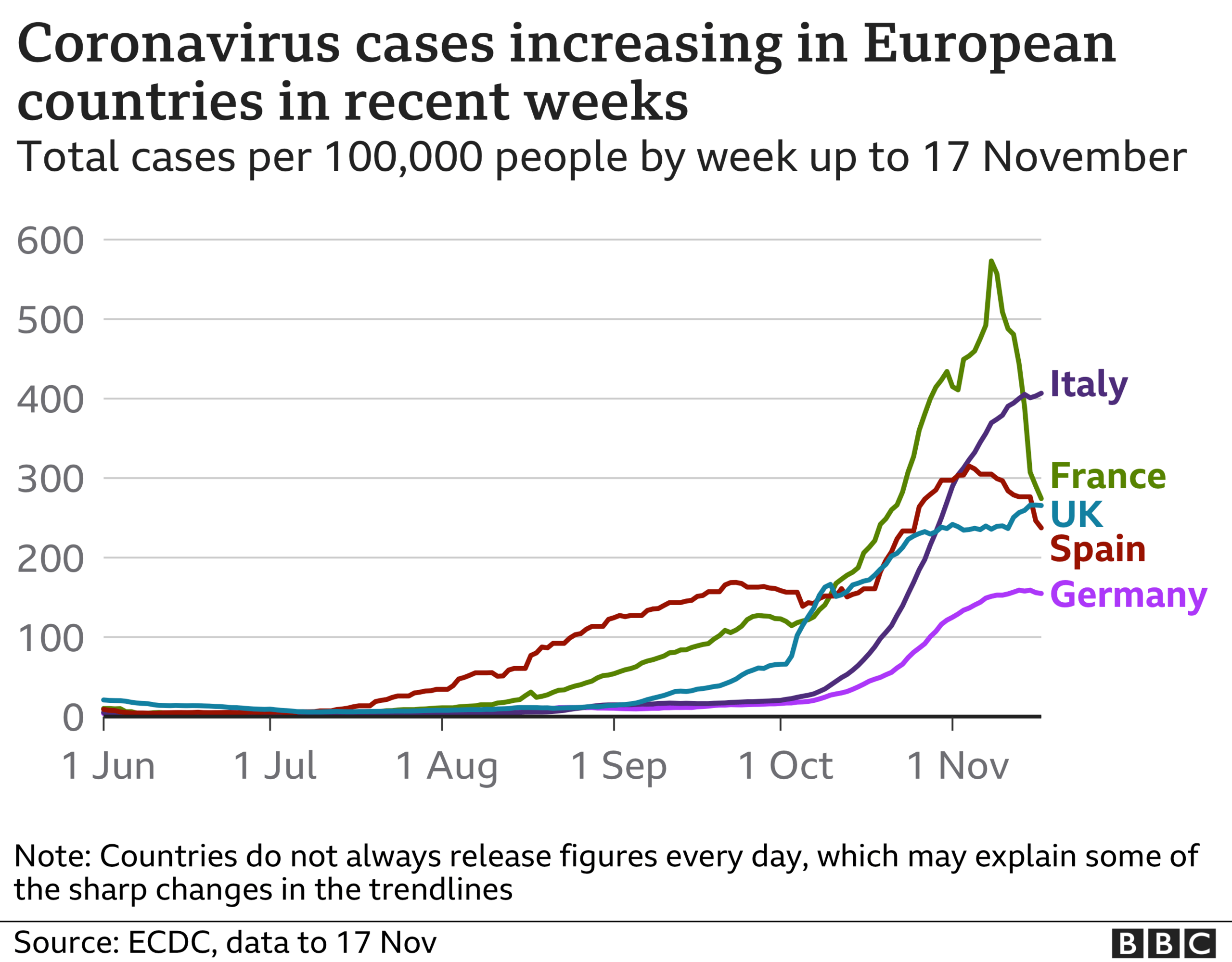

And time is tight. The EU struggled to assert its authority in the early days of the coronavirus pandemic and was hoping to restore its reputation by having recovery funds ready to be spent in January. This dispute makes that even more challenging.

After EU leaders have concluded Thursday's video conference and the two sides have had a chance to assess the scope for deal, we should at least know what rules they're playing by - chicken or poker.

- Published16 November 2020