France Islam: Muslims under pressure to sign French values charter

- Published

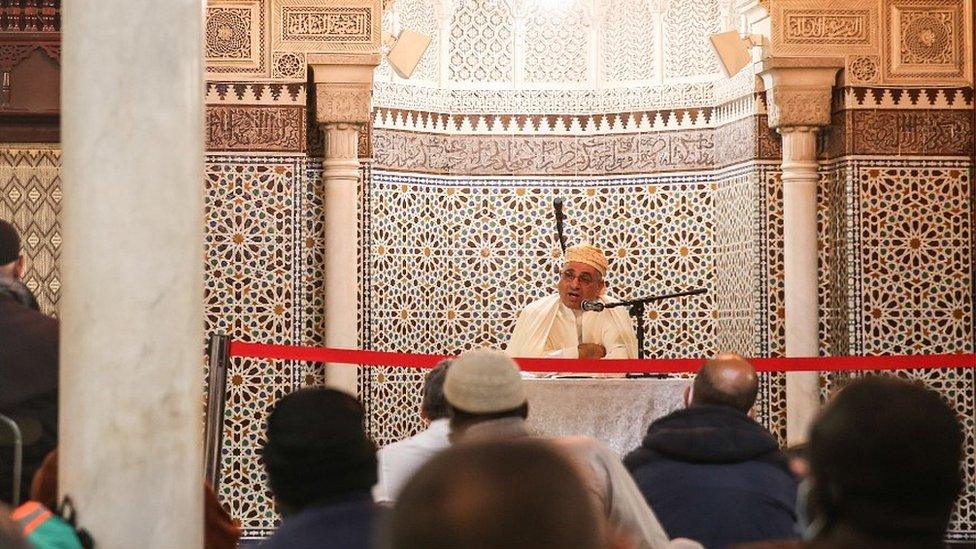

Prayers at the Paris Grand Mosque

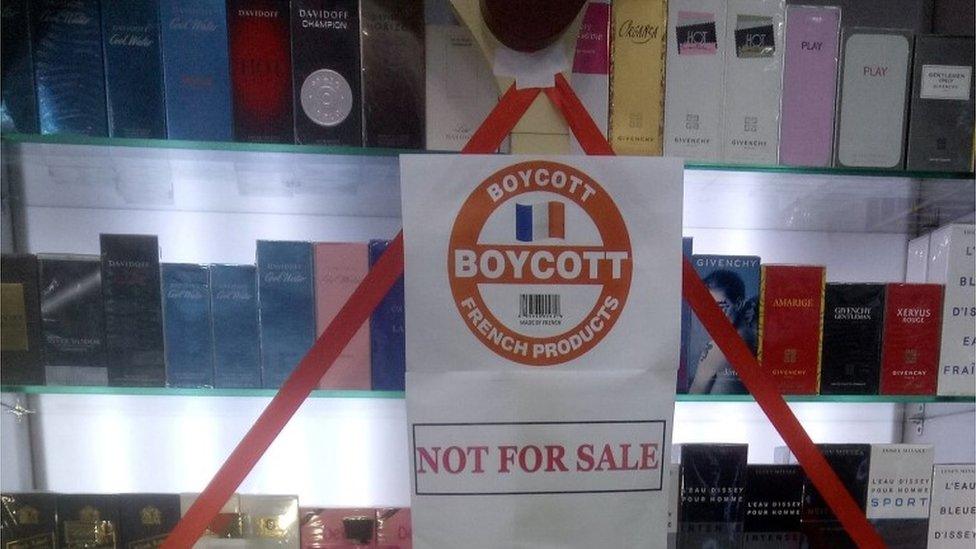

France's Muslim Council is due to meet President Emmanuel Macron this week, to confirm the text of a new "charter of republican values" for imams in the country to sign.

The Council (CFCM), which represents nine separate Muslim associations, has reportedly been asked to include in the text recognition of France's republican values, rejection of Islam as a political movement and a ban on foreign influence.

"We do not all agree on what this charter of values is, and what it will contain," said Chems-Eddine Hafiz, vice-president of the CFCM and Rector of the Paris Grand Mosque. But, he said, "we are at a historic turning point for Islam in France [and] we Muslims are facing our responsibilities".

Eight years ago, he said, he thought very differently.

The Islamist Mohamed Merah had just carried out attacks in Toulouse.

"[Former French] President Sarkozy got me out of bed at 5am to talk about it," he remembers. "I told him: 'His name may be Mohamed, but he's a criminal!' I didn't want to make the connection between that crime and my religion. Today, I do. The imams of France have work to do."

The plan is for the CFCM to create a register of imams in France, each of whom would sign up to the Charter, in return for accreditation.

French President Emmanuel Macron says France 'will never give in'

President Macron spoke in October about putting "immense pressure" on Muslim authorities. But this is difficult territory in a country that cherishes state secularism.

Mr Macron is trying to stop the spread of political Islam, without being seen as interfering in religious practice, or singling out one particular faith.

Integrating all groups of Muslims into French society has become a pressing political issue in recent years. France has an estimated five million Muslims - Europe's largest Muslim minority.

Olivier Roy, an expert in French Islam, says the Charter raises two problems. One is discrimination because it targets only Muslim preachers, and the other is the right to freedom of religion.

"You are obliged to accept the laws of the state," he told me, "but you are not required to celebrate its values. You cannot discriminate against LGBT, for example, but the Catholic Church is not obliged to accept same-sex marriage."

Fashion designer Iman Mestaoui receives regular abuse from those she calls the "haters" - hardline Islamists who say her brand of scarves and turbans does not always cover a woman's hair enough.

But, she says, the idea of getting imams to sign up to "French values" is a problem, when Muslims are already seen by many as not fully French.

"It's putting us in a strange place where you have to show people that you subscribe to the republican values; where you feel French, but they don't feel you are," she explained.

Imam Chalghoumi led a Muslim tribute for beheaded teacher Samuel Paty

"We feel like nothing we do - pay taxes, do [national service] - will be enough. You have to prove that you're really French: you have to eat pork; drink wine; not wear hijab, wear miniskirts. And it's ridiculous."

'Extremist time-bombs'

But Hassen Chalghoumi, imam of the Drancy mosque on the outskirts of Paris, says that after years of terrorist attacks, the government has been forced to act. Mr Chalghoumi is now in hiding, following a spike in death threats over his reformist views.

"We have to go the extra mile, to show that we are well-integrated, that we respect the law," he told me. "This is the price we have to pay because of the extremists."

"It's not a provocation, just my freedom of conscience": Protest over the French law on Muslim headscarves

Outside the Paris Grand Mosque, Charki Dennai arrives for prayers, his rolled-up mat and Koran tucked under his arm.

"These young [extremist] people are time bombs," he says. "I think the imams are a bit too nice to them. We can respect French law and also Islam, it's feasible. That's what I do."

But there are questions over how much influence imams have among younger Muslims, especially when it comes to extremist violence.

"It won't work," says Olivier Roy, "for a very simple reason: the terrorists don't come from Salafi mosques. If you take the biographies of terrorists, none of them is a product of Salafi preaching." Salafism is a hardline, ultra-conservative movement identified with political Islam.

Tackling alienated youth

The charter is one part of a wider government strategy to curb foreign influence, prevent violence and threats from extremists, and win back young people who feel forgotten by the state.

Mr Macron has proposed more Arabic-language teaching in state schools and more investment in run-down areas, and has emphasised that he is targeting Islamists who reject France's laws and values, not Muslims as a whole.

Hakim El-Karoui is a specialist in French Islamist movements at the Institut Montaigne who regularly contributes to government thinking.

"I'm a real fan of the strategy," he told me. "It's comprehensive. It's cultural, and also about organisation and funding."

But, he says, Muslims themselves should be included by the government in projects like this, "because they can do a lot in terms of spreading the enlightened version of Islam on social networks - the government is not able to".

And without the buy-in of "grassroots Muslims", says Olivier Roy, the new Charter will be hard to enforce.

"Let's suppose that the local Muslim community decides to ignore the CFCM and appoints its own imam," he told me. "What will the government do? Either we change the constitution and give up the concept of freedom of religion [or] the government cannot impose certified imams on local Muslim communities."

In a Paris studio, shooting pictures for her new catalogue, Iman Mestaoui tells me she made her whole family vote for President Macron in 2017.

Since then, she has noticed a "huge shift" to the right on issues like immigration and security.

"I was pro-Macron," she said. "He was a real hope in our community, but we feel like we've been abandoned."

- Published21 July 2016

- Published10 February 2020

- Published12 August 2016

- Published19 November 2020

- Published17 November 2020

- Published20 October 2020