Europe migrant crisis: Ten days of Atlantic peril in search of Spain

- Published

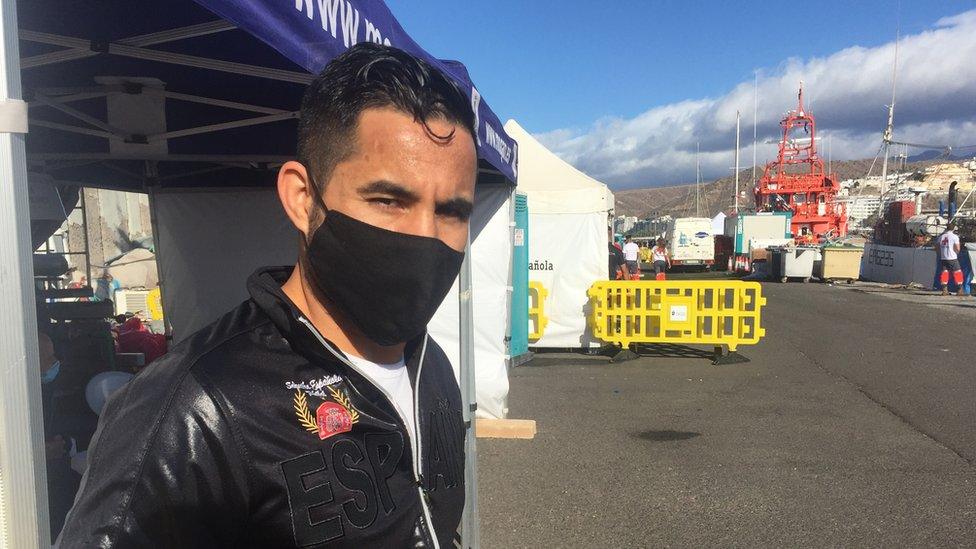

"This is not a good way to travel here, for my brother or for anyone," complains Mohamed Zitouni, a Moroccan man who has lived in Spain for 20 years.

He was looking for his younger brother Rahali - who is one of more than 19,000 migrants who have made the perilous journey across the Atlantic to the Canary Islands in boats from North and West Africa so far this year. From Morocco, the journey takes five days, but from countries further down the coastline it can take twice as long.

The number of arrivals in 2020 is more than 10 times the total number for 2019. "I wouldn't want this for anyone because it's not good, but if it's the only way to make a proper living, what can we do?"

Mohamed Zitouni had gone to find his brother at a wharf on the southern tip of the island of Gran Canaria where at one point some 2,600 migrants had been staying in tents or sleeping rough.

Mohamed Zitouni has lived in Spain for years and now his younger brother has tried to join him

Arguineguín wharf had been used as a makeshift migrant camp ever since the surge in numbers of people arriving or being picked up at sea by rescue services.

They had spoken by phone the previous day, before Rahali's battery ran out. Days after they were reunited, the camp was dismantled.

The emergency caused by undocumented arrivals to the archipelago shows little sign of easing.

In November alone, about 7,000 migrants reached the archipelago, which has seen the highest number of migrant arrivals since 2006.

Conditions on the quayside were cramped and lacked many basic services. In theory, the authorities are allowed to keep them there for 72 hours in order to carry out coronavirus PCR tests and legal procedures, although many migrants reportedly stayed much longer.

Why they make the journey

An increase in controls on other routes from Africa to Europe - across the Mediterranean to Greece, Italy and mainland Spain - has helped make this more perilous journey across the Atlantic more popular.

Relatively good weather conditions have also been a factor.

However, more than 600 migrants have drowned making the crossing this year, according to UN figures.

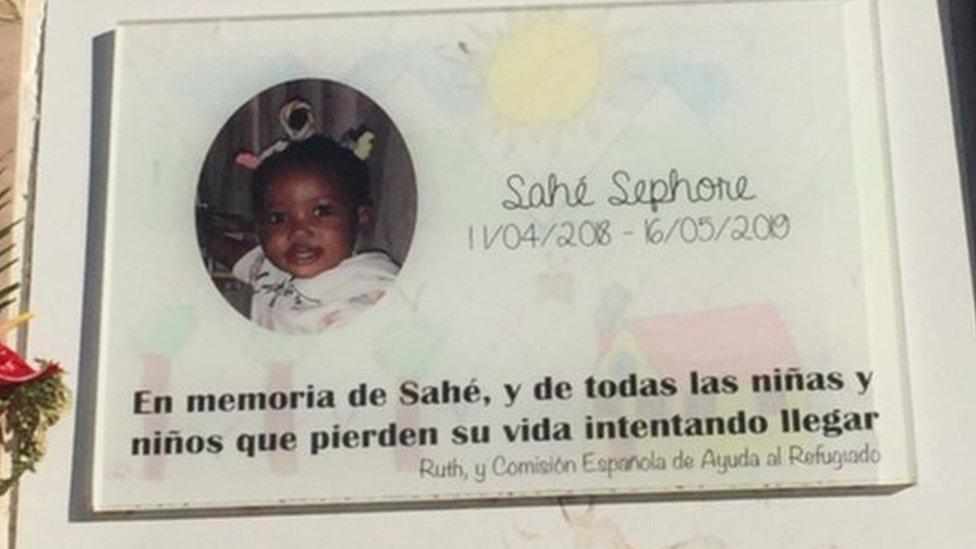

Toddler who drowned on the journey

Sahé Sephore was 13 months old when she and her mother fell in the water as the boat carrying them and some 30 other people hit rocks near the coast of Gran Canaria in May 2019.

She was the first undocumented migrant to be buried formally with their name and surname on a tombstone in the Canaries, reports say.

A memorial in a Gran Canaria graveyard reads: "In memory of Sahé and all the girls and boys who lose their lives trying to get across"

Sea arrivals in Spain in 2020: 35,862

Arrivals in Canary Islands: 19,493

Deaths on Canary Islands route: 650

Source: UNHCR

The Spanish government has been paying for around 6,000 migrants to stay in 17 hotels which had been empty or closed because of the impact of Covid-19 on the local tourism industry. Others are staying in makeshift camps.

A Senegalese man, also called Mohamed, is staying in the Vista Oasis hotel. He made the crossing in September but says he found out that his two younger brothers both drowned while making the same journey since then.

Many of this year's arrivals have crossed from Senegal, a very long and risky journey on the Atlantic

"We have sacrificed a lot to come here, to work, to get a better life," Mohamed told the BBC. "Because in Africa, if you're not from a family linked to the state, or from a rich family, you're not going to live well. That's what Africa is like."

What will happen to the new arrivals?

Having arrived on the islands, Mohamed is now confused about his legal status and whether he will be able to travel on to mainland Spain or another European country, as he would like.

"We've already heard certain rumours, that the Senegalese will have to return home but I don't know if it's true or false," he said. "Right now, many Senegalese are very frightened, because if we return to Senegal, we don't get anything, no work or anything."

Interior Minister Fernando Grande-Marlaska has said that the Socialist-led Spanish government prefers not to transfer migrants to the mainland, in order to "prevent irregular entry routes into Europe".

The administration has started engaging with some African countries, including Senegal, in order to ease the repatriation of migrants, a process that can be legally complex.

'This is an invasion'

Critics have accused the Spanish government of failing to prepare for this crisis, which they say led to chaos on Arguineguín wharf and has put local services under pressure. Ana Oramas, a congresswoman from the Canary Coalition (CC) party, described the situation on the archipelago as "a powder keg".

In recent weeks there have been demonstrations both in favour of and against the immigrants, reflecting the varying reactions of locals to their arrival.

"This is an invasion," said Antonio Santana Hidalgo, who works in the tourism industry. "I respect that everyone has to make a living and survive, but they have to understand you can't just put them up in a hotel with everything included and have them lazing about."

Ailedis Unsué, who works in a bar, has a different perspective.

If their country is doing badly and they have to come here, what else are they going to do?

Hairdresser José María Rodríguez pointed out that Spaniards also had a history of emigration. "People from the Canaries, Galicians and Basques, we all emigrated," he said. "The difference with this type of migration is that they are coming from countries that are at war, where there's no work and things are really bad."

The Spanish government says new facilities currently being prepared will house 7,000 migrants, meaning the hotels will be able to be evacuated.

"I think that, despite the difficulties, we have handled this in an agile way," said Hana Jalloul, Spain's secretary of state for migration.

"We're not going to make a Moria out of the Canaries," she added, referring to the Greek island of Lesbos where fires destroyed an overcrowded migrant camp in September.

"It's not our style of migration policy."

- Published8 November 2020