The Belgian 'hero' who invaded UK fishing waters

- Published

When Victor Depaepe decided to invade England, he knew it would mean a confrontation with the Royal Navy. The thought of backing down never crossed his mind - it was 1963 and Europe was otherwise at peace. But Victor was a man on a mission.

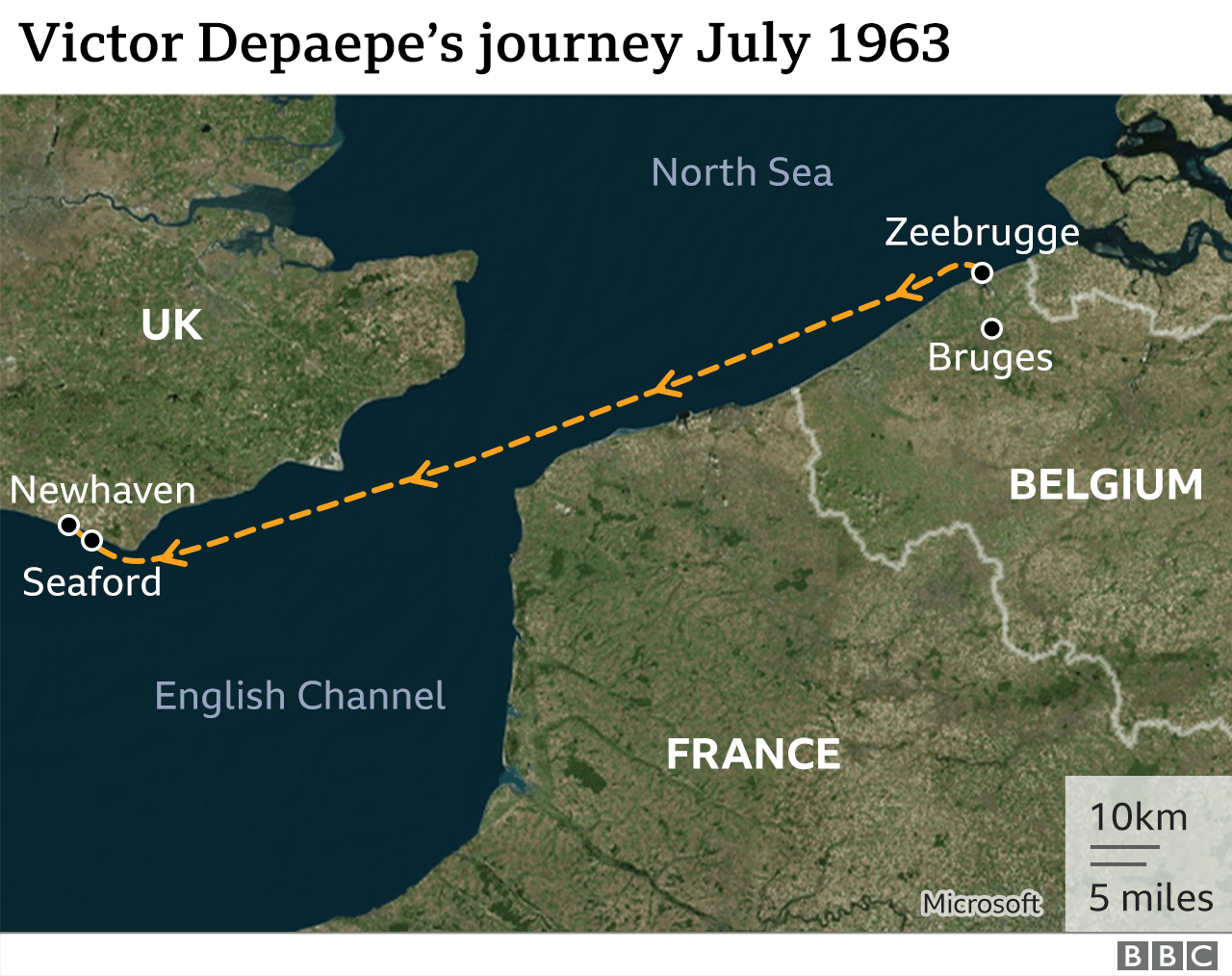

When he set out from the Belgian port of Zeebrugge in his little trawler, he was armed only with a sense of history and a determination to stick up for the rights of his fellow Belgian fishermen.

He had even cabled the Queen and the Admiralty in London before setting sail to reassure them that he was not a pirate: "I am a British-minded man," he explained, "And I am coming as a friend."

Victor wasn't a full-time trawler captain, he was a successful accountant and member of the city council of Bruges, an ancient centre of learning and commerce which was once among the richest cities in the world

For centuries, Bruges was connected to the North Sea by a deep-water canal, and was home to a substantial fishing fleet which by tradition worked the rich waters off the English coast.

Victor was determined to stick up for the Belgian right to carry on fishing in the same seas, although he understood this might provoke powerful emotions in his British friends.

"It's just as if a stranger came into your garden and picked a flower," he acknowledged.

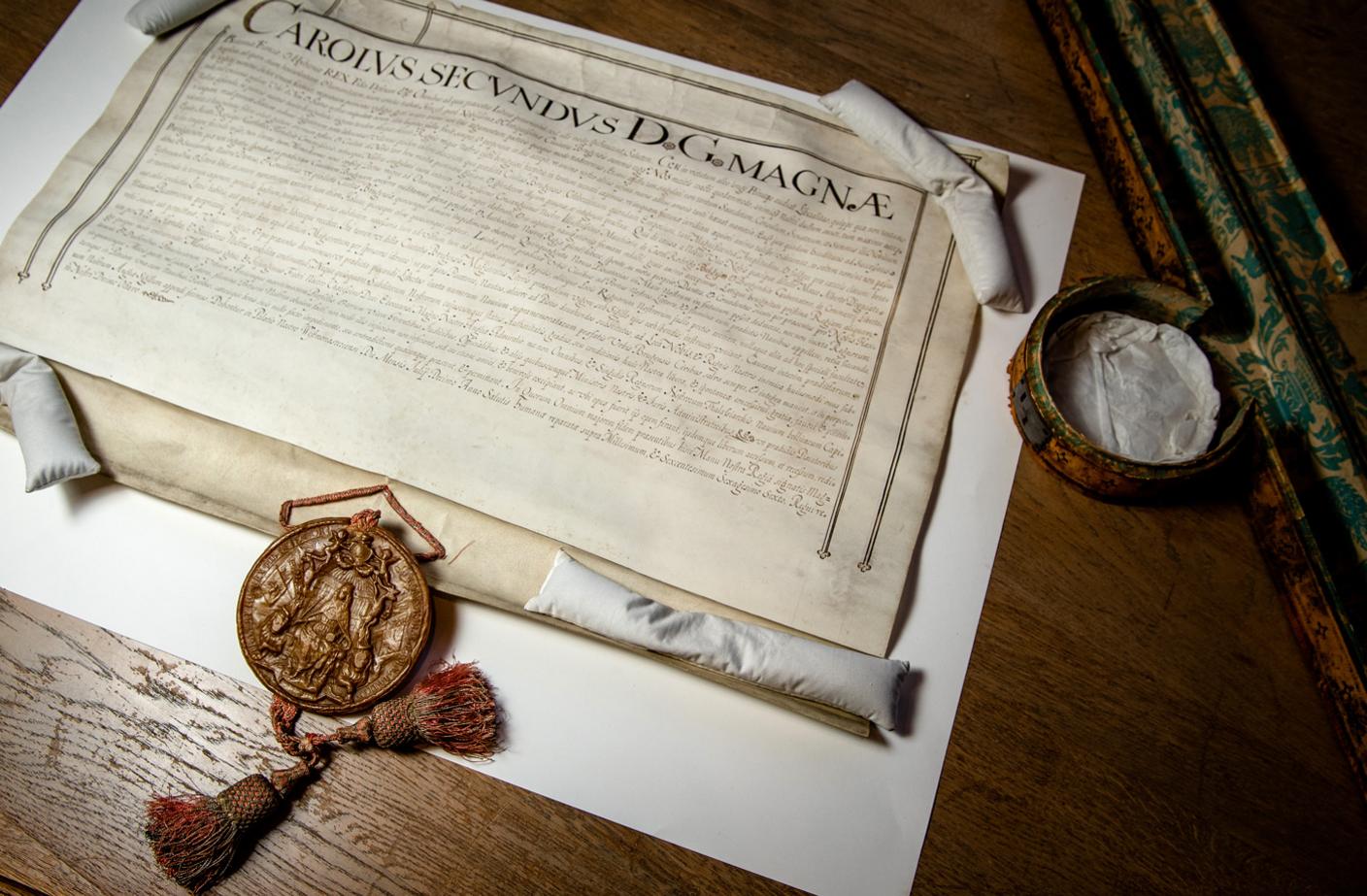

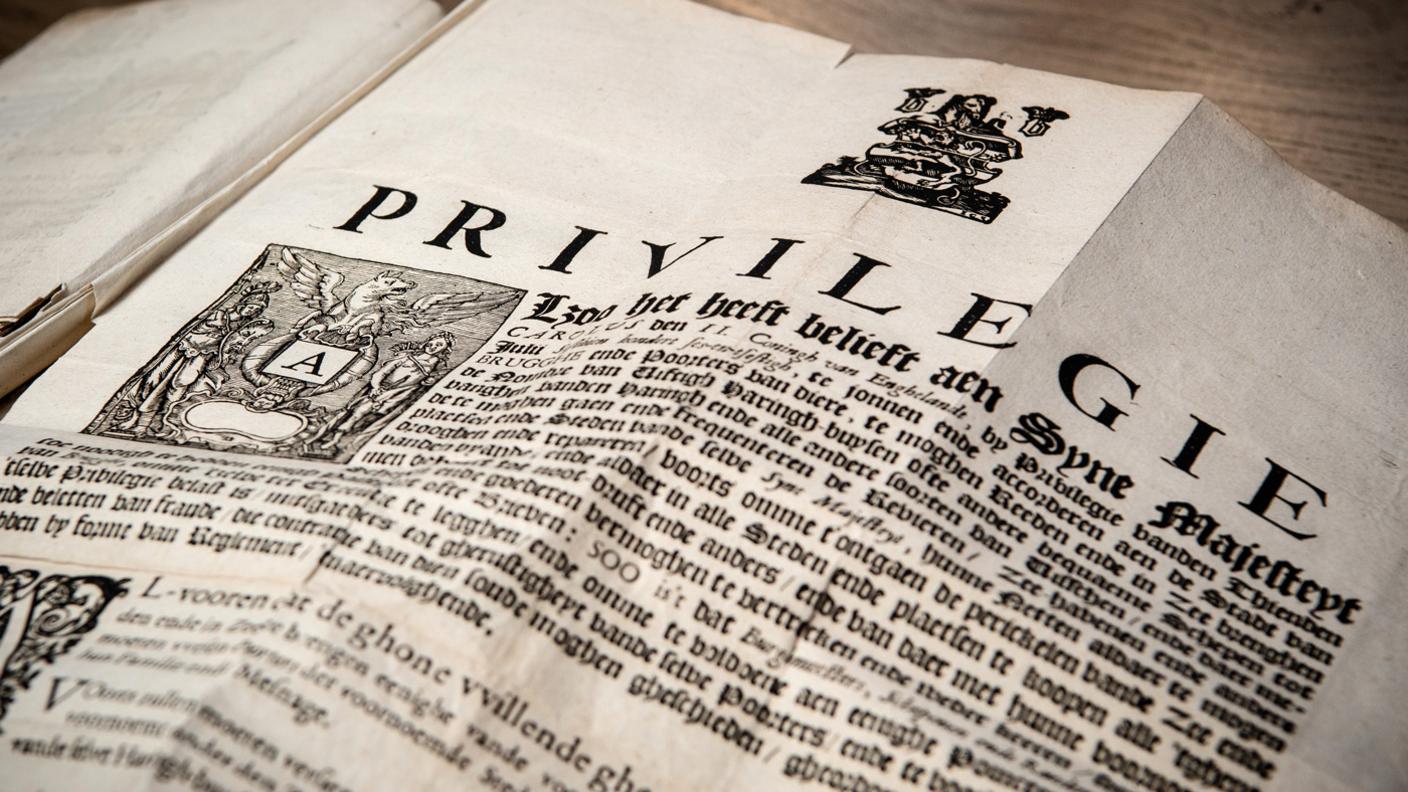

Victor came up with the idea for his invasion - codenamed Operation Charles II - when he discovered a significant document in the Bruges City Archive. It was a charter, written in the King's name, guaranteeing perpetual access to British fishing grounds for 50 boats from Bruges.

After the execution of his father Charles I at the end of the English civil war between Royalists and Parliamentarians, Charles spent part of a period of European exile in Bruges waiting for the restoration of the monarchy.

King Charles II escaping from England in disguise, 1651

In a BBC television report on Victor Depaepe's invasion of 1963, the correspondent rather sniffily describes this as a period of "shameless debauchery".

That may have been part of the reason that Charles felt such enthusiasm for Bruges, but it's interesting to note that as early as the 17th Century the economic value of access to fishing grounds was well recognised.

The charter is an extraordinary document written on a strong but supple sheet of goat skin in florid Latin. It bears a huge, heavy disc of beribboned wax at the base which tells you it's a personal communication from the King himself.

When I touched it - with the permission of the archivist - I found myself reflecting on the extraordinary powers of the monarchy in the 17th Century, and how a single document can make you feel the past is within touching distance.

When Victor, obviously a more practical man, touched it, he calculated that a privilege granted in perpetuity in the 1660s must surely still be valid in the 1960s. He set out to prove it.

Victor's son Paul Depaepe still lives on the Belgian coast not far from Bruges. He was proud to see that as the Brexit negotiations began to stall over the vexed issue of fishing rights, the Belgian government's thoughts began to turn back to Victor's cross-channel operation.

He is proud of his father's adventure, and has collected an impressive archive that tells the story. He has no doubt that the document that Victor unearthed is of lasting importance.

As he explains: "When a king [or queen] makes a law, only another king [or queen] can change it, and so up until now there's been nothing to say that this charter isn't valid any more."

We can't say for sure what role the charter played in the Brexit negotiations, but we do know the Flemish ministry for fisheries forwarded a copy to the European Commission to make sure that it was factored into any deal.

Back in 1963, Victor wasn't just prepared to face the danger of arrest - he positively welcomed it. He was determined to test his theory about the validity of Charles' charter in a British court. That could only happen if he was arrested and charged.

His fellow citizens back in Bruges were cheering him on. Fishermen have known for centuries that rights to work in foreign territorial waters are fragile assets which can be rewritten or revoked at the drop of a hat.

So Paul says his dad was much admired in the Belgian fishing community.

"In the old port of Zeebrugge, my father was a bit of a hero among the fishing community, because even then they always worried about not being able to fish English waters."

Paul Depaepe

Those Belgian crews must have been delighted when word reached them that Operation Charles II had gone like clockwork.

Victor dropped his nets in British waters off the coast of Sussex and was duly arrested as he'd hoped by a Royal Navy motor torpedo boat.

He got his day in court too - appearing before magistrates in Lewes in East Sussex.

At about this point you sense that everyone was beginning to realise that this was no ordinary fishing dispute - and that the polite bespectacled accountant from Belgium might be on to something.

One British newspaper quoted a British official saying that "he is keener to be prosecuted than we are to prosecute him". And that was indeed the case - Victor wanted to settle the legal point about royal charters once and for all.

Victor Depaepe arriving in Newhaven, July 1963

In the finest traditions of stories of adventure on the high seas, I'll ask you to wait for a moment to hear how Victor's invasion turned out.

His legal dispute is still well-remembered by the crews of Belgium's modern fishing fleet, whose chronic anxiety about their access to English territorial waters deepened as the Brexit negotiations dragged on.

Job Shot works out of the port of Ostende, just a short distance down the coast from Bruges, and takes his boat, the Job Senior, into the rich waters off the coast of Sussex every week.

Job Shot, fisherman

His catch normally includes sole and turbot, brill, red gurnard and plaice. And while these are tough times in the age of Covid-19 (the closure of the restaurant trade has cut wholesale prices in half), the Channel has provided his family with a living for centuries.

The Shots have been sailing these waters since around 1700 - just a few years after Charles II issued that fateful charter - and Job says all fishing disputes historically have been about politics and diplomacy. Relations with English crews themselves, in the same sea area where Victor Depaepe got himself arrested, are good, he says.

"From what I see this is a purely political issue. In the area where we fish we never have a problem with these guys."

For Job, a stable deal which goes beyond Brexit and includes the Belgian fleet is the only outcome which guarantees a future for him and his family.

Belgium's short coastline means its territorial waters are not big enough to support its fleet, and he makes the point that the Channel is French as well as English.

He says if a long-term deal can't be found, it would be the end of his company.

"When it's forbidden to fish inside the 12 miles or so of English waters it's over for me - 80% of my catch comes from English waters. Of course I'm concerned for the future - I have four grandsons and they tell me they want to be fishermen. What am I going to say to them, 'There is no future for you because English waters are closed for us?'"

This began as a story about fishing rights and Brexit - and by a strange historical quirk the powers of the Stuart monarchy after the restoration.

But at its heart is a story of relationships, which are so deep and so ancient that you find yourself wondering if Brexit itself won't one day seem like just one more point of detail in a very long story.

It's not just about the medieval wool trade that thrived between Flanders and East Anglia either. Two of the most celebrated regiments of the British Army were founded in Bruges to protect Charles II when he lived there - the aristocratic cavalry of the Life Guard and the Grenadier Guards. Flemish bricklayers helped build London, and British artists and architects helped restore the ancient glories of Bruges during the great artistic revival of the 19th Century.

Bruges

No-one can put that relationship in context like Brigitte Beernaert, an architectural historian who works for Bruges City Council and is such an Anglophile that she's the only non-British person I've ever heard referring to Europe as "the Continent".

She says simply: "The English and Bruges is a love story. Brexit was a complete surprise to us, but England is England - something special."

Brigitte traces the relationship back to a woman called Emma of Normandy who, back in the 11th Century, was wife to two kings of England (Aethelred the Unready and Cnut) and mother to a third (Edward the Confessor). Emma made her home in Bruges for years, and in the 1,000 years which have followed, so have many others.

Brigitte Beernaert, architectural historian

Bruges became one of the first places that modern British tourists began to visit, and that tradition has persisted through endless changes of historical circumstance.

Brigitte says that flow of tourists was important to the citizens of Bruges too: "English tourists and the English have been part of our daily life since I was a little girl," she told me. "Every year we had the visit of parties of English schoolboys and that was a very familiar and traditional sight."

The British path to Bruges was set long ago. In the 19th Century, a tradition developed of visiting the battlefield of Waterloo near Brussels.

Bruges was a convenient stopping off point on the way, after you'd caught your steamer to Ostende and before you continued your pilgrimage to the site where the British and their Prussian and Dutch allies had finally seen off the threat of Napoleon.

"I cannot imagine that British people will stop coming to Bruges," says Brigitte. "It cannot be that Britain is going to drift away from us. They need us like we need them."

And the history really does matter.

Victor Depaepe after all first heard about Charles II's charter when he was leafing through a copy of the Illustrated London News - a magazine which offered a serious and classy chronicle of important historical subjects and world events.

When we left Victor earlier in this piece he was up before magistrates in Lewes facing rather serious charges of illegal fishing.

And here's the remarkable thing.

After the trial had started, a message reached the court from government lawyers that the case should be quietly dropped pending further legal reflection.

'He was a hero'

The British government had no desire to test in public the validity of the Bruges Charter and the legal power of personal decrees made by Kings and Queens in open court. To Victor and to the fishing crews of Bruges that was a tacit admission that the fishing privileges granted by a grateful Crown around the time that Sir Christopher Wren was designing St Paul's Cathedral remained valid around the time the Beatles were beginning to top the charts. And no-one in the UK, it seems, cared to contradict him.

Victor's son Paul says the fishermen of Bruges recognised his achievement: "He was a hero," he told us simply.

This year of course the charter has been just one ingredient in a more complicated diplomatic cocktail of Brexit and fisheries negotiations, free trade deals and withdrawal agreements.

But the fact that it's played a part at all is testament to the deep ties between Britain, Bruges and Belgium, and above all to Victor Depaepe - an Anglophile and an adventurer with a sense of humour and a sense of history.

Video/stills: Bruno Boelpaep; Research: Sira Thierij