Steinmetz Swiss trial: Jail for tycoon in Guinea mine corruption trial

- Published

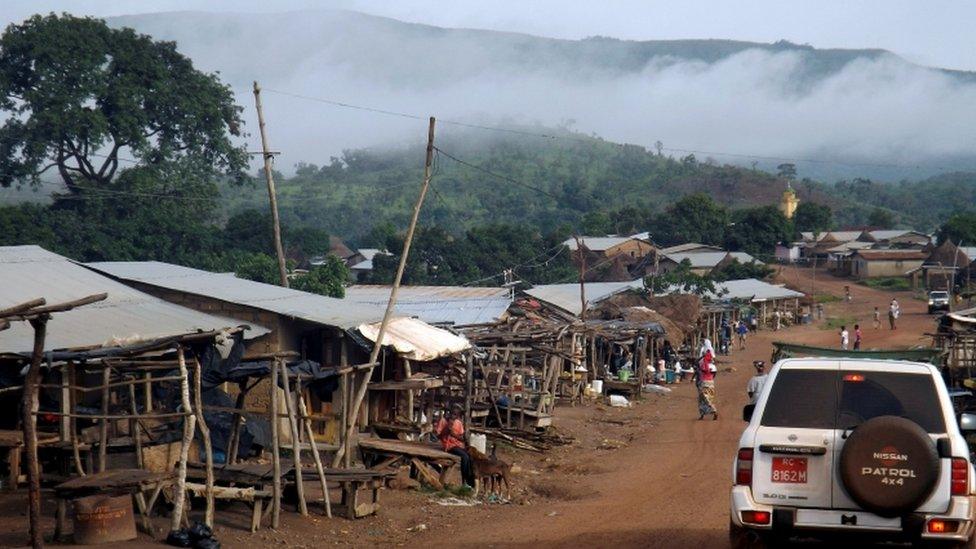

The Simandou mines are thought to have some of the most valuable untapped iron ore deposits in the world

Israeli businessman Beny Steinmetz has been given a five-year jail sentence by a court in Geneva, in a trial described as the mining sector's biggest-ever corruption case.

The trial threw a spotlight on an often murky struggle for control of Africa's natural resources.

Steinmetz, a former diamond magnate who also holds French citizenship, was convicted of bribing public officials in Guinea, in order to gain control of the country's iron ore deposits.

The court also ordered him to pay compensation of 50m Swiss francs (£41m; $56m) to the state of Geneva.

"It is clear from what has been presented... that the rights were obtained through corruption and that Steinmetz co-operated with others," to obtain them, Chief Justice Alexandra Banna told the court, according to AFP news agency.

Steinmetz, who has always denied bribery, condemned the verdict as a "big injustice". He plans to challenge the verdict and will not go to jail pending the appeal, his lawyer said.

The Simandou mines, in south-eastern Guinea, are estimated to be the most valuable untapped iron ore deposits in the world.

The case dates back to 2006 when, according to the prosecution, the businessman, working for a company called Beny Steinmetz Resources Group (BSGR), paid bribes so that BSGR could acquire mining rights in Simandou. These had originally been held by mining giant Rio Tinto.

The former diamond magnate now lives in Israel but was based in Geneva until 2016

The trial took place in Switzerland because Mr Steinmetz lived in Geneva until 2016, and ran businesses there. Some of the bribes, the prosecution said, were paid through Swiss banks.

Key witnesses and hot shot lawyers

Steinmetz now lives in Israel, but travelled to Geneva to appear in court in person, hiring one of Geneva's most high-profile lawyers, Marc Bonnant, to defend him.

The court found that Steinmetz, 64, and his two co-defendants had paid $8,5m (£6,2m) in bribes to a wife of Guinea's late president Lansana Conté, who died in 2008. They were found guilty of setting up elaborate schemes to hide the link between BSGR and Conté's fourth wife, Mamadie Touré. She had been scheduled to appear in court herself but did not turn up. She now lives in the United States.

Defence lawyer Mr Bonnant told the trial that Steinmetz had never "paid a cent" to Ms Touré, and that anyway she was never actually legally married to President Conté, and therefore under Swiss law did not qualify as a bribable public official.

What's more, Mr Bonnant said, some of the alleged bribes were paid after President Conté's death, which made no sense at all: "How do you bribe a ghost?" he asked the court.

Only a 'spokesperson'

But the prosecution presented evidence which, it said, proved there was a trail of bribery and corruption stretching from Geneva, via Liechtenstein, to the Virgin Islands and back again.

Another high-flying Geneva lawyer, chief prosecutor Yves Bertossa, scored points questioning Beny Steinmetz. Since it was a fact that BSGR had acquired the mining rights for Simandou, he asked, how did Mr Steinmetz not know about the financial transactions that led to that acquisition?

Yves Bertossa argued that Swiss rules limiting prosecution of public officials to 15 years in the past did not apply in this case

Beny Steinmetz, who cut a subdued figure in court, and sometimes, speaking in French, stumbled over his responses, insisted he had only been an "adviser" or a "spokesperson" for the company that bears his name.

When confronted with details of the alleged bribery, as well as transcripts of conversations, his frequent response was: "I don't know. I wasn't involved and I don't know the details."

Mr Bertossa produced details of a conversation (recorded by the FBI in 2013) in which one of Steinmetz's co-defendants appeared to try to persuade Ms Touré to get rid of evidence of corruption, mentioning a certain person "up there" at BSGR who made all the decisions. "Who's 'up there'?" asked the prosecution.

"I don't know who is up there," replied the businessman. "There may be God, but not me."

Even when the prosecution produced evidence of meetings, emails, and money transfers that allegedly proved bribery had taken place, Steinmetz denied all knowledge of them, leading Mr Bertossa to scoff that it seemed highly odd that Beny Steinmetz knew nothing about the workings of a company called Beny Steinmetz Resources Group.

Steinmetz was questioned in 2017 as part of an Israeli investigation

Beny Steinmetz is no stranger to investigations into his financial affairs. He has been questioned at least once by Israeli authorities, and was recently convicted of money laundering (in absentia) in Romania, in a case believed to be linked to the Guinea bribery scandal.

Historic trial

For observers of the trial, including non-governmental organisations that for years have followed the tangled web of BSGR's finances, the trial has been historic.

Agathe Duparc of Swiss NGO Public Eye, which focuses on big Swiss businesses and multinationals based in Switzerland, said the case had "starkly revealed the inner workings of international corruption, against the backdrop of one of the poorest countries in the world".

While the trial had sent a strong signal to the commodities sector, it also showed that Switzerland should tackle legal loopholes that allowed such "predatory practices," she said.

Swiss justice has become much more active

In fact this very public trial took place against a backdrop of other moves aimed at cleaning up Switzerland's financial sector, and proving the country has put some of its more questionable financial practices behind it.

In November a nationwide referendum, which would have made businesses domiciled in Switzerland legally responsible for human rights violations and environmental damage along their supply chains anywhere in the world, won the popular vote but not the required number of cantons.

Nevertheless, the Swiss government, mindful of public opinion, has introduced new legislation for Swiss businesses, requiring them to report on human rights and environmental standards and conduct due diligence when it comes to child labour and mineral sourcing from conflict areas.

At the same time, Switzerland's Attorney General is conducting painstaking investigations into global financial scandals in which there may have been some Swiss involvement, including Malaysian state wealth fund 1MDB and Brazilian oil giant Petrobras.

Just last week Swiss prosecutors said they had opened an investigation into money laundering and embezzlement linked to Lebanon's Central Bank.

Big implications for mining industry

This case has much wider implications than the fate of Beny Steinmetz.

When BSGR acquired the Simandou mining rights, it did not extract any iron ore. A few years later, BSGR sold the mining rights to Brazilian multinational Vale for an estimated $2.5bn. Vale has yet to show an interest in Simandou either.

The alleged bribery emerged when Guinean leader Alpha Condé ordered an audit into the Simandou mines

Businesses and their shareholders in places far from Guinea have done extremely well trading those mining rights.

The people of Guinea themselves have got precisely nothing - and the iron ore deposits, described by Agathe Duparc as "fabulous" resources, lie untouched, the Simandou region undeveloped and lacking in investment.

It's a story that NGOs such as Public Eye insist is repeated across Africa. In the fight for control of highly valuable mineral resources, unscrupulous businesses see ways to get rich quick, and there is little control of their financial practices.

The bribery in Guinea only came to light when, after the death of President Lansana Conté, his democratically elected successor Alpha Condé ordered an audit into the Simandou mines.

It has been seven years since the Steinmetz investigation was opened.

This trial is now likely to bring more pressure on Switzerland to prevent what Public Eye calls "predatory practices that deprive the populations of resource-rich countries of essential revenues".