Bag packed but Russian activist avoids jail

- Published

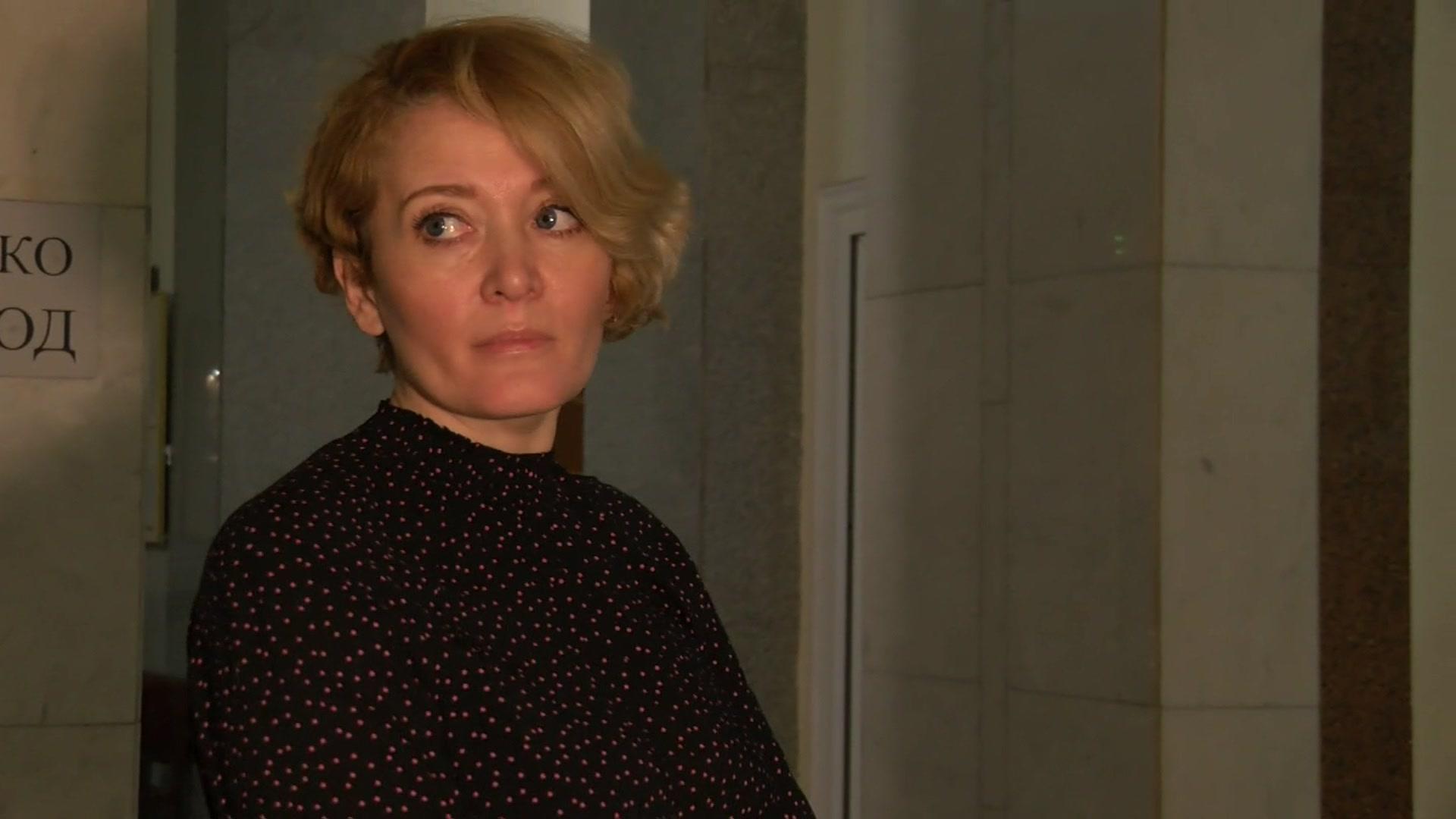

Ahead of the verdict, Ms Shevchenko (left) was preparing a bag ahead of her possible prison term

Anastasia Shevchenko spent the past week packing a bag for prison and recording voice messages for her children to listen to in case she was jailed. The prosecutor had requested five years behind bars for the single mother of two, in the southern Russian city of Rostov-on-Don.

So when the judge declared her guilty but announced a suspended four-year sentence, it came as a moment of relief for the family in court. Her mother, Tamara, cried quietly as the judge read out her ruling.

The opposition activist was placed under house arrest over two years ago, accused of links to a pro-democracy group based in the UK and banned in Russia under a controversial 2015 law on "undesirable organisations". The judge on Thursday also lifted her house arrest.

Ms Shevchenko said she was unhappy with the guilty verdict, but her son Misha said it was "the best day of my life"

"I'm not afraid, but I worry about my family," the 41-year old activist had told me on the eve of the verdict, as she sorted through the large bag of items for prison that she was taking with her to court.

She had been banned from entering most shops under the terms of her house arrest, so her teenage daughter Vlada collected everything together - including a notebook to keep a prison diary, warm socks and cockroach traps.

The BBC spoke to Anastasia Shevchenko about life under home arrest in February 2020

'Threat to state security'

The case against Anastasia Shevchenko stemmed from a political seminar and an authorised protest in 2018, when she stood in a central Rostov park with a banner declaring she was "fed up" with Vladimir Putin.

Ms Shevchenko stood in the centre of Rostov holding a flag that read #Fed Up

The investigator claimed that she was acting on behalf of a banned organisation, with "criminal intent", and that her actions constituted a "threat to state security". For months, the English teacher was kept under surveillance with a secret camera installed above her bed.

Her lawyers said no evidence of foreign-backed subterfuge was ever captured as a result.

The defence team also argued that the Open Russia opposition movement Ms Shevchenko belonged to, which is legal, has no formal ties to a very similarly named organisation based in Britain which was founded by the Kremlin critic and tycoon-in-exile Mikhail Khodorkovsky.

Protesters took to the streets in Moscow in 2019 when Ms Shevchenko was charged with "participation in the activities of an undesirable organisation"

"Debates, seminars, political rallies are our right to express our opinion!" Ms Shevchenko argued of the activity that led to her arrest. "I don't know where I committed a crime. I really didn't. But they treat me like a very dangerous person."

Tolerance of open dissent has sunk even lower since Ms Shevchenko's detention in January 2019.

The jailing of the opposition politician Alexei Navalny last month sparked the biggest street protests this country has seen in years.

President Putin now talks even more frequently of foreign agents and outside "meddling": he argues that the West is trying to destabilise and weaken Russia, using the opposition as a tool.

Many people linked to Navalny have been charged with a myriad of crimes.

Anastasia had been steeling herself for the worst, since the prosecutor in her own case asked for a five-year prison sentence - more than expected and even longer than term handed down to Navalny.

"I recorded a message today telling you I love you," she told nine-year old Misha, as he lay on his bunk bed playing computer games.

Anastasia Shevchenko had prepared her two children Misha and Vlada for her possible absence

She had also filmed videos for 16-year-old Vlada with instructions on things like reading the electricity meter and turning on the oven, just in case.

The family have been sharing a bed lately, anxious to be as close as possible for whatever time they've got.

'Be more responsible'

In her final speech to the court last week, Anastasia Shevchenko asked whether the state hadn't "sucked enough blood" from her family and called on the judge to "be human".

Her eldest daughter, Alina, who was severely disabled, fell ill while Anastasia was under arrest and the activist only got permission to see her in hospital shortly before she died.

She still hasn't been able to scatter the ashes.

"I asked them to be more responsible. To realise what they are doing to our family," Ms Shevchenko told me, adamant that the case against her was "absolutely false".

Related topics

- Published24 January 2020