EU closes ranks over Covid surge and vaccine delays

- Published

German officials said they hoped 80% of the population would be inoculated by autumn

Europeans, like many others across the world, hoped for a better and happier year in 2021 - after seemingly endless months of Covid illness, deaths and pandemic-linked economic misery.

But so far, so annus horribilis for the EU. On a number of Covid fronts.

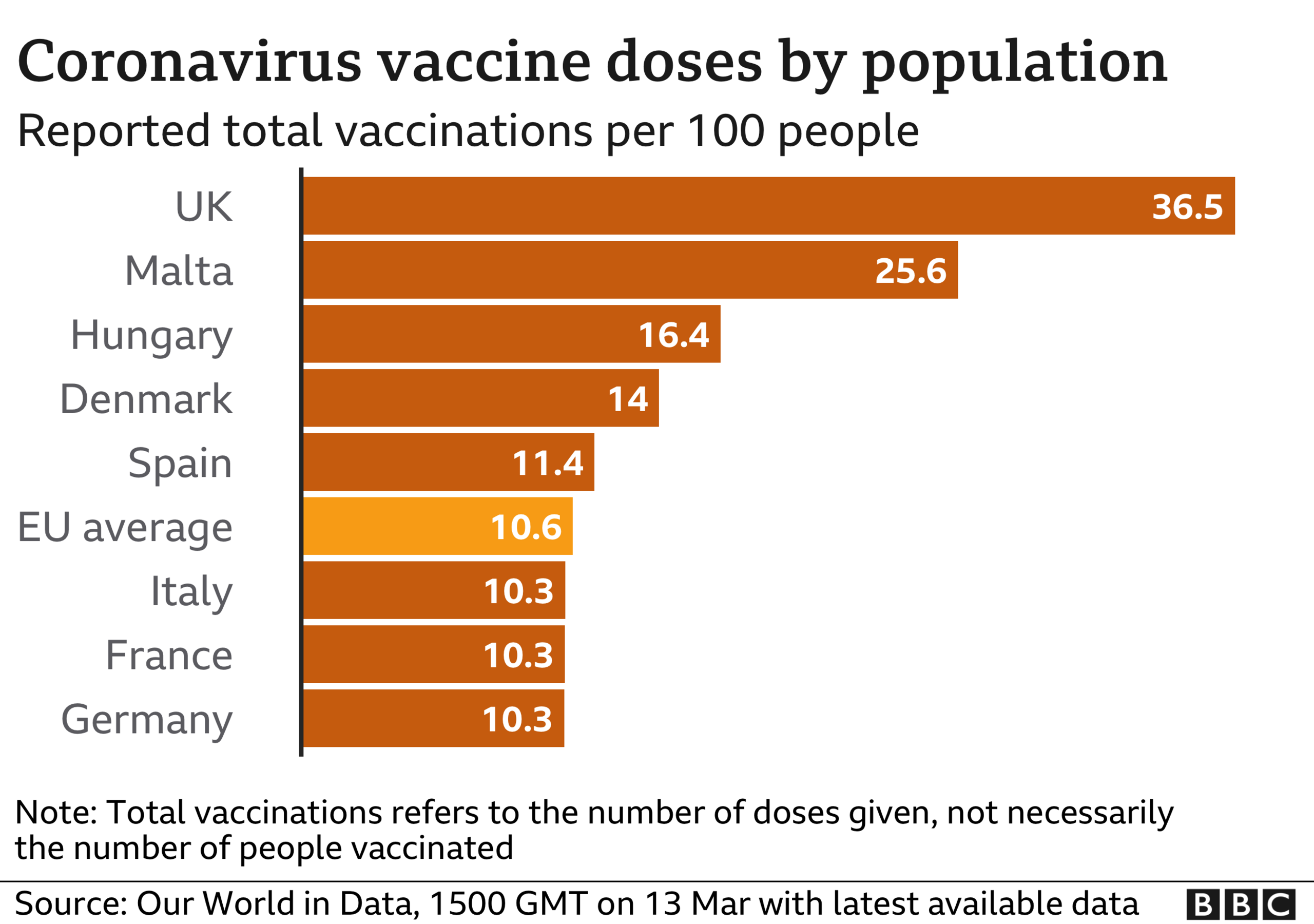

The bloc's by now infamous vaccination procurement scheme - trumpeting the securing of up to 2.6 billion doses - has so far failed to deliver. EU countries lag significantly behind Israel, the UK and the US in getting jabs into arms.

A number of EU members have stumbled nationally, too, with heavily criticised roll-outs of the vaccines they did manage to obtain, in Germany, Belgium, Bulgaria and beyond.

And all the while the virus continues its deadly spread.

On Friday, Italy's Prime Minister, Mario Draghi, and Germany's respected Robert Koch institute for infectious diseases confirmed their respective countries were experiencing a third wave of the pandemic. Covid restrictions in Italy will be tightened from Monday, with a national lockdown planned for Easter Weekend.

Countries in Central and Eastern Europe, proud of their health record during the first Covid wave, are now suffering terribly.

Infection levels in Poland have returned to previous peaks seen in November as Central Europe is hit by a surge of cases

Poland and Hungary have seen serious spikes in infection, while the Czech Republic and neighbouring Slovakia report some of the highest death rates per population in the world.

This was certainly not what the European Commission had in mind back in June when it announced a "European strategy to accelerate the development, manufacturing and deployment of effective and safe vaccines against Covid-19".

At the time, the UK was derided by many at home and abroad for not accepting an invitation from Brussels - even as a departing member state - to jump aboard the EU vaccine procurement scheme.

"Boris Johnson's Brexit-focused government prefers to go it alone? More fool them," was the sentiment of many in the EU.

But fast forward to late February and take a look at the front-page headline of Germany's popular Bild newspaper. In a mixture of German and English and with the union flag as a backdrop, it reads in bold print: Liebe Britain, We Beneiden You ( Dear Britain, we envy you).

This from a country with the famously level-headed scientist Angela Merkel at its helm and which, at the start of the pandemic, seemed to lead the way in how to deal with the virus effectively.

So what went wrong?

The debate in Germany has become highly politicised in the lead-up to September's general election.

The secretary general of the Social Democrat Party, a bitter election rival of Chancellor Merkel's CDU, announced that Germany should never have handed over power to the European Commission to purchase vaccines on its behalf. Vice-Chancellor Olaf Scholz reportedly described EU efforts as a horror show - and with even stronger words than that.

A few weeks ago there was talk of European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen possibly having to resign over the fact that contracts signed with vaccine producers came late and weren't tight enough to guarantee delivery.

European politicians and voters alike wanted to know why the UK was able to get all its vaccines but the EU wasn't.

But the EU mood has shifted slowly since.

Ursula von der Leyen (belatedly) admitted that mistakes were made and EU governments privately acknowledge they share some of the blame as they were consulted by Brussels before it negotiated the vaccine contracts on their behalf.

In February the head of the European Commission insisted on Europe's "fair share" of vaccines

An EU diplomat, representing an influential member state told me the frustration felt by people across the EU was understandable.

"We hate to see our loved ones and the vulnerable still exposed to the virus when counterparts elsewhere are protected by vaccines we can't access as fast as we expected." But, he added, on reflection the Commission had done "an excellent job".

Could it have been better?

"Undoubtedly," he answered. "But the complexity of the EU has its price."

The European Commission has been heavily criticised for having been too bureaucratic in its approach to vaccine contracts and for focusing too much on AstraZeneca - which has ended up seriously defaulting on delivery to the EU.

But EU insiders say a number of countries originally favoured Astra Zeneca as a cheaper option. The Pfizer vaccine was seen as pricey and I'm told a number of member states were suspicious that Germany had an agenda: to make money for the German business BioNtech behind the vaccine.

By now though, there's a growing feeling in the EU that they're "all in it together", bearing in mind the single market and the open-border Schengen Agreement.

This was the opinion of one European politician I spoke to on condition of anonymity. "We're not protected at all if we're not all vaccinated at a European level," he told me.

"Going it alone could never have really been an option, even for the rich countries. So the pan-EU plan is really an investment in each of us."

That said, the European Commission is hardly off the hook.

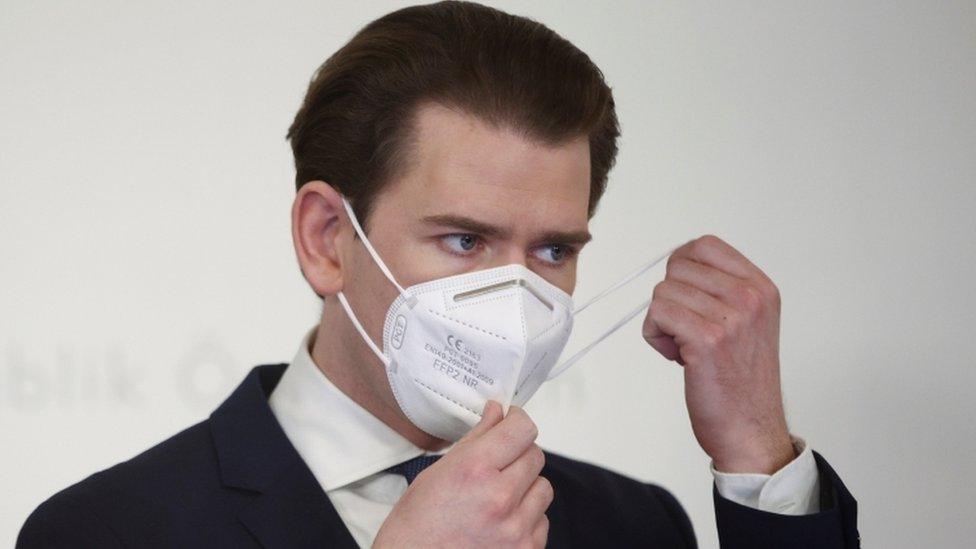

On Friday, Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz accused it of presiding over a vaccine "bazaar" and failing to distribute jabs according to each country's population size, despite an agreement to do so. A charge the Commission denies.

Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz said on Friday that vaccine doses were not being distributed fairly within the EU

And the European medical body the EMA consistently comes under fire for being "slow" to approve vaccines.

Now that a number of EU countries have shown an interest in vaccines from Russia and, to a lesser extent, from China, the Slovak Prime Minister, Igor Matovic, announced he would like to send "a little message to the head of the EMA: 'Dear Christa, we would all be very happy for you to change your working hours at the EMA for the following months to 24 hours a day and 7 days a week - and to approve vaccines not in three months but in three weeks. It's a matter of life and death'."

At the same time though, there is a growing sense of the EU closing ranks.

Smaller and less well-off member states were always grateful to have access to any vaccines at all. Thanks to Brussels, they say, they can vaccinate at the same time as wealthy France and Germany. An impossible prospect had they been left to fend for themselves.

Increasingly the EU finger of blame points outwards: at governments outside the bloc and at pharmaceutical companies.

Even well-known Brussels critic Viktor Orban, the Hungarian prime minister, recently admitted that vaccine deliveries agreed by the EU were "constantly delayed and rescheduled".

The EU has approved the use of four vaccines so far: Moderna, Oxford-AstraZeneca, Johnson and Johnson and BioNtech-Pfizer.

What happens if I don't get the Covid vaccine? Laura Foster explains

Each and every one has posed delivery problems.

Above all, AstraZeneca. The EU expected around 100 million doses of the AZ vaccine by the end of this month but AZ is struggling to deliver even 40 million. It's now feared it will be pushed to honour commitments to the EU from April, too.

This has led to a blame game with the UK government, as AstraZeneca has not defaulted on its deliveries there.

The European Commission insists that its contract with AZ included promises of vaccine delivery from the company's UK-based plants, too.

Privately some EU diplomats describe Brussels' digs at the UK as "childish".

"I don't understand those in the EU who can't praise the UK where praise is due," one EU insider told me. "The government there has done a great job getting vaccines. The NHS is doing amazing work with the vaccine roll-out. And we should openly say that."

He was also heavily critical of how the French President Emmanuel Macron had "attempted to make out the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine was sub-standard", only to row back from those comments later.

France started slowly but said on Friday that a one-day record of 300,000 vaccinations had been carried out

"You can't blame the UK for working with AstraZeneca to its best advantage," was the opinion of another diplomat I spoke to. "You have to blame the company itself for selling the same vaccine twice over yet only delivering to one of its clients."

AstraZeneca denies wrongdoing and points out its contract with the EU requires it to make "best efforts to supply".

The EU's trade commissioner took to Twitter this week to declare, one presumes with intended irony, that AZ was making efforts to deliver to the EU - but not "best efforts".

Adding to the fraught atmosphere, as governments push to protect - and be seen to be trying to do their best to protect - their populations against the virus - is the fact that EU-UK relations are already strained after Brexit and they are particularly prickly because of ongoing disagreements over the implementation of the Brexit agreement for Northern Ireland.

The head of the European Council Charles Michel said his accusations against the UK were based on facts

Tempers were easily inflamed on both sides of the Channel again this week when European Council President Charles Michel accused the UK of having an outright export ban on Covid vaccines.

This assertion was described by the UK government as "completely false".

The UK does not in fact have an explicit export ban on vaccines. Nor does the US, although Charles Michel also accused Washington of having one, yet the EU continues to ask the UK whether it has actually exported any vaccines to the bloc.

By contrast, the EU this week declared itself to be "the leading provider of vaccines around the world", exporting more vaccines than it has access to, because of the number of production sites based in the EU.

The European Commission pointedly declared the UK as the biggest recipient of vaccine exports from the EU to date - receiving approximately 9 million doses or components of doses, it said.

The EU was hitting back at criticism for an authorisation mechanism it has put in place for vaccine exports from pharma companies that have failed to honour their contractual commitments with the EU.

The EU has a long list of less well-off countries exempt from export controls and so far the mechanism has been used once only to actually stop vaccines from leaving the EU. A week ago Italy blocked the export of 250,000 doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine to Australia, sparking considerable controversy.

While some in the EU favour a much tougher stance on exports, as long as pharma companies fail to deliver to the bloc, others I speak to think that would be a terrible idea, affecting the EU's image abroad.

"Just look at the soft power Russia and China are exerting by bestowing their vaccines around the world," one of the diplomats I spoke to said to me.

"The EU has to step up and honour its commitments to those less fortunate than ourselves. It's a moral and political imperative. At the moment these vaccine rows are a stupid competition between rich, privileged nations. I hope we can co-ordinate our international obligations at the upcoming EU leaders' summit."

But the hopes of many EU leaders for that end-of-month summit lie far closer to home. The European Commission has promised a dramatic increase in vaccine deliveries as of April. With 300 million vaccines to be delivered by July.

Europeans are crossing their fingers that this time it's a promise the Commission can make good on.

- Published21 June 2021

- Published11 March 2021

- Published10 March 2021

- Published6 March 2021

- Published25 February 2021

- Published20 February 2021

- Published5 March 2021