Camille Pissarro: Transatlantic struggle for painting stolen by Nazis

- Published

Paris under occupation: Nazi Germany controlled the French capital from June 1940

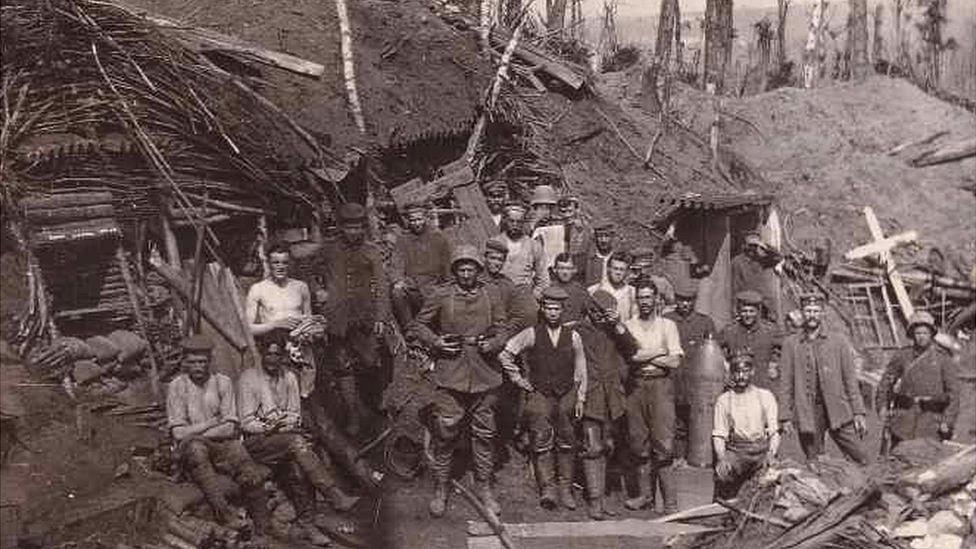

Eighty years ago, Nazi officers entered a local bank in a sleepy corner of south-west France, and raided a safe deposit box there.

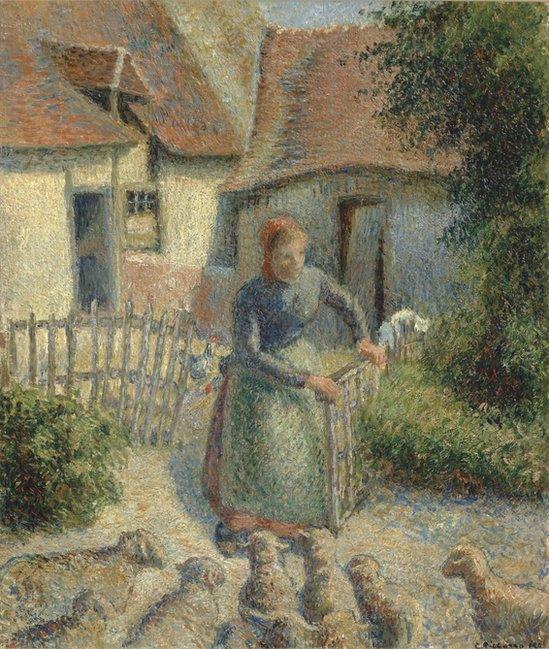

Hidden inside, they found a stack of artworks, including a painting by Impressionist artist Camille Pissarro, showing a shepherdess bathed in warm light greeting her flock.

The painting had been hidden there by a Jewish couple, Raoul and Yvonne Meyer, the heirs of famous French department store Galeries Lafayette. It was 1941, and France had already been under German control for a year. The Pissarro canvas disappeared into Nazi custody.

A 'model' rotation agreement

No-one disputes this story. But the painting itself, found hanging in an Oklahoma art gallery in 2012, is now the subject of an unusual custody agreement, and a bitter transatlantic dispute over restitution rights in cases of stolen Nazi art.

The painting, La Bergère Rentrant des Moutons (Shepherdess Bringing in Sheep), was traced to the US by the Meyers' adopted daughter, Léone-Noëlle, now in her 80s.

It had been gifted to the University of Oklahoma's Fred Jones Jr Museum in 2000 by an American family who had bought it in good faith. Mrs Meyer wanted to reclaim it and bring it back to France.

Now 81, Léone-Noëlle Meyer has asked the French courts to stop the painting returning to the US

The agreement she reached with the museum in 2016 stated that both parties would share possession of the painting; that it could not be sold, exchanged or donated without the permission of both sides; and, crucially, that the picture would be rotated between the Oklahoma museum and a French art gallery every three years.

It was, in the eyes of the university's Foundation, "a model for how to fairly and justly settle modern day art restitution cases", and rightly "heralded as a first of its kind".

The question of how to weigh the rights of current owners against those of the original pre-Nazi owners has never been fully settled.

At heart is the legal concept of "good faith": whether those who bought an artwork in good faith from a legitimate source should have to give it up, and whether they should be compensated if they do. Different courts and different countries have often applied different rules.

Solution 'imposed by Oklahoma'

Mrs Meyer's lawyer, Ron Soffer, says she was "forced" to sign the agreement with Oklahoma University, because the statute of limitations for claiming the painting had expired.

"Because they were not willing to restitute it, Mrs Meyer found herself with a substantial risk of not seeing the painting ever return to France," he told me. "It was a solution imposed by Oklahoma. It goes from Oklahoma to a French museum and then back to Oklahoma. Mrs Meyer does not even have the ability to touch it."

Stranger still, he says, is a clause in the agreement that requires Mrs Meyer to gift the painting to a "mutually agreed upon French art institution" before her death. If she does not, the painting "shall be permanently transferred… to the US Art in Embassies program".

Challenging the painting's return to US

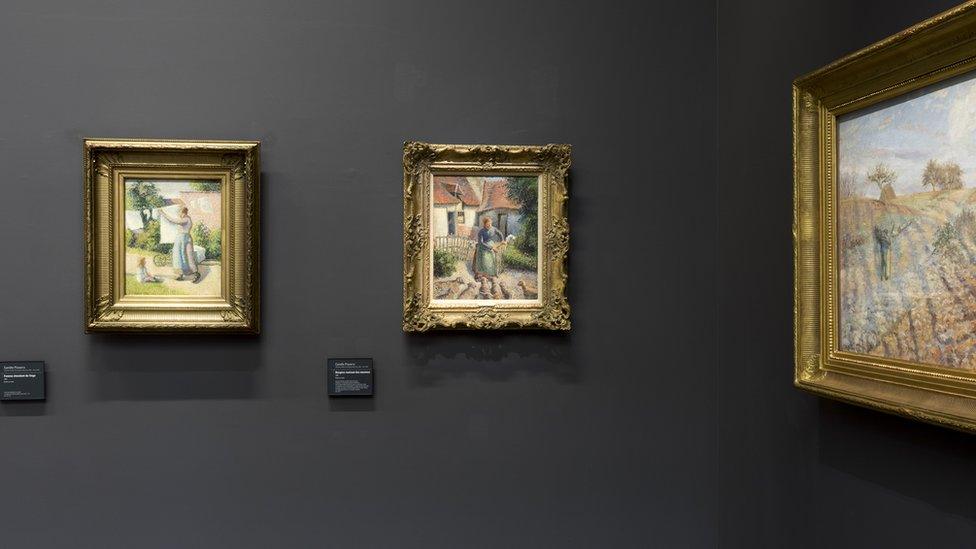

Since 2017, the painting has been hanging in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris on its first rotation in France. But Mrs Meyer is having trouble gifting the work to the museum, the home of French Impressionist art, because of the requirement to ship it back and forth to the US every three years.

La Bergère Rentrant Des Moutons is for the moment hanging in the Musée d'Orsay

In a statement, the Musée d'Orsay expressed the "difficulties" and "cost" involved in the project, citing the need for "regular transport of the work between Paris and the University of Oklahoma". It had no comment on any legal action.

The painting is due to leave for its three-year rotation in the US at the end of July.

Mrs Meyer, now 81, has asked the French courts to intervene to stop the Pissarro from leaving. They're due to give their first verdict on the case next month.

Daily fine for 'violating agreement'

In response, the district court in Oklahoma has ruled Mrs Meyer in contempt, with a stinging judgement that she "has largely forfeited whatever sympathy she might otherwise have been entitled to", having "entered into a rigorously negotiated settlement agreement… then violated that settlement agreement when it no longer suited her purposes."

The US court has imposed a daily fine on Mrs Meyer - said by her lawyer to be $2,500 (£1,800) a day, in addition to legal fees - for as long as she continues the case in France.

"It is disappointing that she is actively working to renege on the agreement lauded by the international arts world," said the Oklahoma University Foundation.

The American Alliance of Museums and the Association of Art Museum Directors have both warned that "parties to future disputes may be reluctant to enter into agreements", if the original settlement in this case is not upheld. Nazi-era claims should be resolved in an "equitable, appropriate, and mutually agreeable manner", they say.

An 'unfavourable' claims process

Mrs Meyer's lawyer, Ron Soffer, sees it differently.

"The important question is to ask why Oklahoma has been fighting for the past decade not to restitute a painting that they do not contest is of dubious origin, that they do not contest was taken from Mrs Meyer's adopted father by the Nazis?" he said.

Restitution expert Marc Masurovsky says one major problem facing claimants like Ms Meyer is the lack of international agreement or of government support.

"The claims process has been really unfavourable to claimants from the very beginning," he says, "and apart from those who are extremely well-equipped financially, politically and legally, many claimants decided not to push for the return of their property because it was a real headache."

Regulations like France's 1945 decree on Nazi plunder have been invoked differently by courts on different sides of the Atlantic, he says.

"If we'd had more public sector involvement in this," he told me, "we may have been able to eliminate these situations where you have to go before a judge who knows almost nothing about the Second World War, and certainly nothing about plunder and the way Jews were exploited".

'A new approach' to stolen art

David Zivie, who heads the Research and Restitution Mission at France's culture ministry, says there was a big effort just after the war to find the owners of artworks brought back to France from Germany: 45,000 items were returned to their original owners at the time.

But from the 1950s to 1990s many countries, including France, did not see restitution or research of artworks as a priority. "When it was an artwork from the national collection, the minister and the museums were really reluctant," he told the BBC.

But attitudes are changing. France last month agreed to return a painting by Klimt from its national collection to the heirs of its original owner in Austria.

France's culture minister said restoring Klimt's Rosiers sous les Arbres to its rightful owners was an acknowledgement of what they had suffered

"There is a strong political will to do the research and listen to the families, and try to find just and fair solutions," said Mr Zivie. "We can say that it's a new approach."

Mrs Meyer inherited the painting from her adopted parents after losing her biological family to the Holocaust. "Seeing this painting get back to France is very, very important to her," Ron Soffer explained.

"We frankly do not understand how Oklahoma could possibly justify to themselves and to their students the notion of getting an 81-year-old Holocaust survivor sanctioned in order not to yield a painting that they know belongs here."

Find out more about the struggle to reclaim art stolen by the Nazis

Where has this Nazi art gone?

Related topics

- Published15 March 2021

- Published24 November 2019

- Published28 December 2015