France arrests ex-members of Italy extremist group Red Brigades

- Published

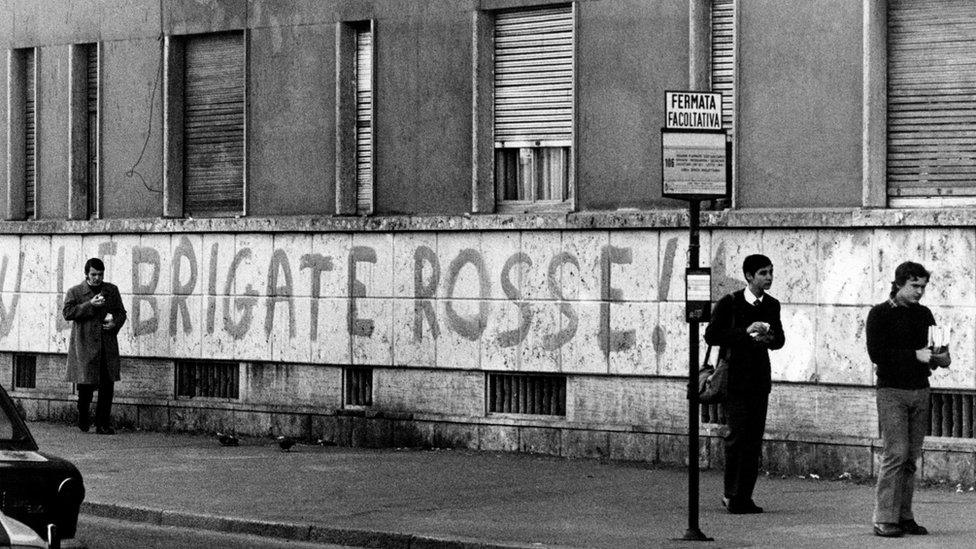

The Red Brigades sowed chaos at a time of social and political turmoil in Italy

France has detained seven former members of far-left Italian militant groups, including the Red Brigades.

The seven, and three other Italians still being sought, had been convicted of terrorism charges in Italy dating back to the 1970s and 1980s.

France had offered left-wing radicals protection from extradition under a controversial policy.

Italy's prime minister welcomed the arrests, saying the crimes had "left a wound that is still open".

The Red Brigades and other militant groups carried out violence in Italy during the so-called Years of Lead.

The period, from the late 1960s to early 1980s, got its name from the vast number of bullets fired.

The Red Brigades were blamed for numerous killings, including the 1978 abduction and murder of former prime minister Aldo Moro.

What do we know about the arrests?

The arrests on Wednesday involved members of the Red Brigades and a co-founder of the far-left militant group Lotta Continua.

In the 1980s, France's then Socialist president François Mitterrand offered Italy's far-left radicals protection from extradition under the "Mitterrand doctrine", on the condition that they renounced violence and had not been accused of bloodshed.

The policy has long been a source of tension between the two countries, with Italy calling on France to hand over some 200 people.

The French presidency on Wednesday said the arrests did not mark a break from the Mitterrand doctrine, because Mr Mitterrand himself had said that those with blood on their hands should not be protected. But it said they were part of efforts to resolve tensions.

"France, also affected by terrorism, understands the absolute necessity of providing justice for victims," a statement said. "With this transfer, it is also part of the urgent need to build a Europe of justice in which mutual confidence must be at the centre."

Officials in France said the arrests followed months of discussions between the two countries.

Since taking office in February, Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi has established a close working relationship with French President Emmanuel Macron.

Why has France acted now?

The Mitterrand doctrine meant that ex-Red Brigaders would not be troubled by French police as long as they were now leading ordinary, innocent lives.

Crucially, and this bit is often forgotten, President Mitterrand also said this rule should not apply to members who the Italian authorities could show had blood on their hands. Suspected killers would not be protected, but extradited to face justice.

In practice this never, or rarely, happened. Only two former members of the Red Brigades have been sent back. One of them, Cesare Battisti, fled to South America in 2004 before he could be handed over. His eventual extradition to Italy was from Bolivia.

One reason for this was the strong support for the militants in France's left-wing intelligentsia. Another was the claim that the Italian justice system would not treat them fairly. The Italians were obviously furious.

Today, because the original intention was always, in theory, to send back to Italy the worst alleged offenders, President Macron can argue that he's not actually breaking with the Mitterrand doctrine. But he is certainly breaking with precedent.

What has the reaction been?

Italian Justice Minister Marta Cartabia hailed a "historic" action.

Foreign Minister Luigi Di Maio said the arrests proved that "one cannot run away from one's responsibilities, from the pain inflicted, the harm caused".

But the lawyer for five of the detainees called the arrests an "unspeakable betrayal on France's part".

"Since the 1980s, these people have been under the protection of France. They've remade their lives here for 30 years in the full view and knowledge of everyone, with their children and their grandchildren... and then in the early morning, they come looking for them, 40 years after the facts," Irène Terrel told AFP.

It is not yet clear what will happen to the detainees.

French Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin told France Inter radio that it was up to a French court to decide whether they would be extradited.