Hvaldimir: Seeking sanctuary for whale dubbed a Russian spy

- Published

The tame beluga whale has been living in waters off Norway's coast for more than two years

A mysterious beluga whale was dubbed a spy when he appeared off Norway's coast wearing a Russian harness. Two years on, little more is known of the animal's past, but now activists are concerned for his future welfare.

One campaign group led by an American filmmaker wants to create a sanctuary and is urging Norway to support it.

The whale's first known sighting in Norway came at the end of April 2019, when a blob of white flashed past fishermen near the islands of Ingoya and Rolvsoya.

This was strange because belugas are rarely seen this far south of the high Arctic. Stranger still was the harness wrapped tightly around the whale's body.

The whale was wearing a harness when he first appeared off Norway's coast

The whale seemed to be seeking help. A concerned fisherman, Joar Hesten, sent images to marine biologist Audun Rikardsen, who contacted the Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries for assistance. Seafaring inspector Jorgen Ree Wiig was dispatched to investigate.

"I saw the whale, thinking this is really something," Mr Ree Wiig told the BBC. "I knew this situation was quite unique."

The fisherman put on a survival suit and jumped into the icy water, freed the whale and retrieved the harness. To his surprise it had a camera mount and clips bearing the inscription "Equipment St. Petersburg".

The clip bore the name of a Russian city, St Petersburg

An investigation was launched by Norway's domestic intelligence agency, which has since told the BBC "the whale is likely to have been part of a Russian research programme".

Russia has a history of training marine mammals such as dolphins for military purposes and the Barents Observer website has identified whale pens, external at three different locations near naval bases in the north-west area of Murmansk.

The purpose of the pens and the origin of the whale have never been officially addressed by the Russian military.

A retired Russian colonel, Viktor Baranets, told Reuters news agency he had been informed that the scientists in Russia's north were "using beluga whales for tasks of civil information gathering, rather than military tasks".

Norwegians were captivated by the whale's dramatic rescue. Because of the whale's apparent spy status, he was given a tongue-in-cheek name. In a nod to hval, Norwegian for whale, and Russian President Vladimir Putin, the beluga was christened Hvaldimir.

Is this whale a Russian spy?

Within days of his rescue, he had taken up residence in the harbour at Hammerfest, a coastal town of about 11,000 people. The first few weeks there were rough for Hvaldimir, who was struggling to feed himself.

To save his life, Norway's fisheries directorate approved a programme to monitor and feed Hvaldimir.

The beluga recovered, left Hammerfest harbour and started feeding independently. Since 19 July, 2019, he has been a "free-swimming" whale, according to the Norwegian Orca Survey, which ran the feeding programme.

American film-maker Regina Crosby, a part-time resident in Norway, saw cinematic potential. She set out to make a short film, but is still awaiting a happy ending.

"Nothing was what I thought it was," she told the BBC.

"I thought it was going to be a happy story about a whale escaping from the Russian military. I thought it was going to be done in a week. But as time went on, no-one was doing anything for this whale."

That was when her campaign began.

Seafaring inspector Jorgen Ree Wiig says he is prepared to give any idea to help Hvaldimir a fair hearing

For a sociable animal that seeks out human interaction, dangers abound, and Ms Crosby felt Hvaldimir needed protection.

Boat propellers, fishing nets and tourists are among the most severe threats. By the end of 2019 her campaign had begun and when others joined her cause activist group OneWhale was formed.

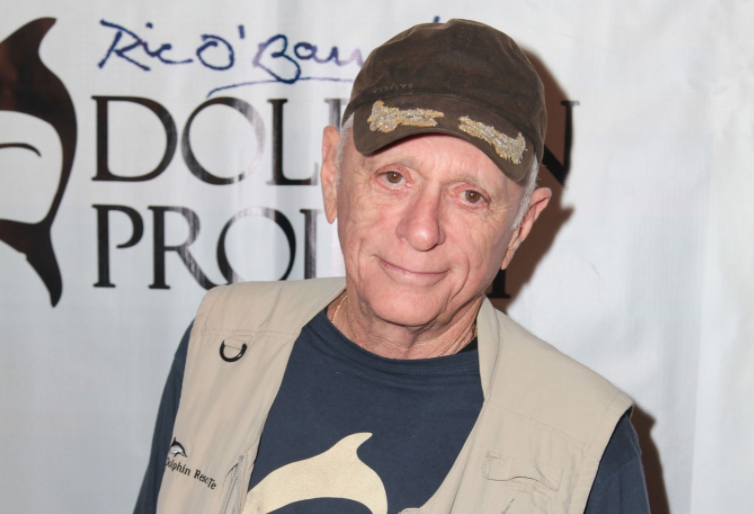

Against keeping the whale in captivity, they decided to keep Hvaldimir safe and, if possible, return him to the wild. Ms Crosby sought expert advice from American activist Ric O'Barry.

Ric O'Barry has been campaigning against marine-life captivity for decades

A former dolphin trainer, he has since spent decades campaigning against captivity and featured in The Cove, an Oscar-winning documentary about the slaughter of dolphins in Taiji, Japan.

"Whenever a dolphin or a whale is in trouble, my phone will ring," Mr O'Barry told the BBC.

One call from Regina Crosby and he was on a plane to Norway in July 2020. When he arrived Hvaldimir had suffered a nasty gash across his body, apparently inflicted by a boat.

Urgent action was needed, Mr O'Barry believed. "My thought was to swim him into a fjord."

Fjords are abundant along Norway's coastlines. The long, narrow waterways stretch far inland from the sea. Perhaps one could be sealed off and turned into a secure sanctuary, he thought.

Hvaldimir's connection with humans is putting him in danger, activists say

All Ms Crosby had to do was convince Norway's government - a country with a history of whale hunting.

For months, OneWhale has been in talks with government agencies about creating a sanctuary for Hvaldimir and other stricken marine wildlife in a disused fjord.

The group's idea is for "an enormous, open-water marine wildlife reserve" in a fjord at least two kilometres long (1.2 miles) and one kilometre wide. The mouth of the fjord would be closed off by a sub-sea net and there would be a cabin with facilities for staff.

OneWhale says two communities in northern Norway have expressed serious interest and funds have been approved for studying the sanctuary's impact. "Right now it's very much a green light," said Ms Crosby.

OneWhale has suggested creating a marine reserve in a fjord in northern Norway

Not everyone agrees with the idea. Mr Rikardsen, the marine biologist, said the whale seemed to be in good health, feeding at different fish farms.

"As far as Norway is concerned, he's a free-living whale," said Mr Ree Wiig, an observer for the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission. "I think the situation now is the best one."

For him keeping an animal in a closed-off fjord is "not a Norwegian thing to do". "But if someone can convince me otherwise, I'm open-minded. If there's a good plan, I think the government would consider it."

Marine scientists are sure Hvaldimir has been trained by humans in captivity

Various government agencies need to give their approval and Norway's fisheries directorate told the BBC it had discussed the idea with OneWhale and believed Hvaldimir should be "left alone and given the opportunity to live as a free animal" if he was not at great risk.

Mr O'Barry fears such freedom could mean a life of solitude for the whale and argues that sanctuary care "may be the best we can do".

He points to a dolphin sanctuary he founded in West Bali, Indonesia, where former captive animals are assessed for their fitness for life in the wild. If not, they remain in the sanctuary for the rest of their lives.

For now, Hvaldimir eats and sleeps at a fish farm, where a hungry whale is not particularly welcome.

He is free to roam, occasionally seeking humans to fulfil his social needs. He seems to share an affinity with humans that's as dangerous as it is endearing, because of the apparent captivity he endured.

Videos of him playing with tourists appear on social media from time to time, heightening concern for his welfare.

His self-appointed guardians visit whenever they can. Ms Crosby described how the whale recently chased her boat when it started to leave. Hvaldimir slowly faded from view, a blur of white below the setting sun.

Beluga whales are extremely sociable mammals that usually live in pods

Related topics

- Published4 April 2019

- Published16 April 2019

- Published22 July 2020