France's Le Pen on track for regional power with an eye on presidency

- Published

Marine Le Pen is a popular visitor as she goes on walkabout in the coastal village of Le Brusc

Not so long ago, a walkabout by French far-right leader Marine Le Pen would announce itself with some heckling, maybe a protester or two, a few tight lips among observers, and the sense of wary curiosity that surrounds someone outside the political mainstream.

This time it was only a glimpse of blonde hair at the heart of the scrum that gave it away, as the head of France's far-right party inched slowly through Brusc market near Toulon, posing for selfies with her supporters every few yards.

Polls suggest her National Rally party [formerly the National Front] will top Sunday's first-round vote in around six of France's 13 regions this Sunday. And it is on track to win at least one, Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur (PACA), in the run-off vote next weekend.

"You're virtually on home turf here!" one journalist shouted to Mrs Le Pen as she toured the Côte d'Azur. Behind her, ripe cherries were piled high on the stalls, and bottles of olive oil glinted in the sun.

"I tend to think I'm on home turf everywhere," she responded drily.

Winning in a vast region like this, with a budget of billions, would mark a turning point for her party, which currently controls just a dozen town halls in France and only one city.

Dry run for 2022 race against Macron

This is also a crucial test of the party's electoral strategy ahead of the presidential race next spring, when Marine Le Pen is again tipped to face President Emmanuel Macron in the second round.

In both elections, her strategy rests on winning over mainstream conservatives. Mr Macron needs to do much the same, setting the stage for a battle over France's traditional centre right.

No accident, then, that the National Rally's regional candidate for this coastal region, Thierry Mariani, used to be a member of the main centre-right Republicans party.

Thierry Mariani is favourite to win the key southern PACA region for Ms Le Pen's National Rally

No accident either that Marine Le Pen has worked hard to appear electable and politically safe, emphasising the party's "calm" and "responsible" approach to change, and lecturing government ministers on upholding democratic principles.

Macron steers clear of Le Pen duel in south

In the market, Rose pauses her shopping to confide that the party's new image is indeed winning over some conservatives.

There are a lot of people around me, right-wingers like me, who are going to try the National Rally

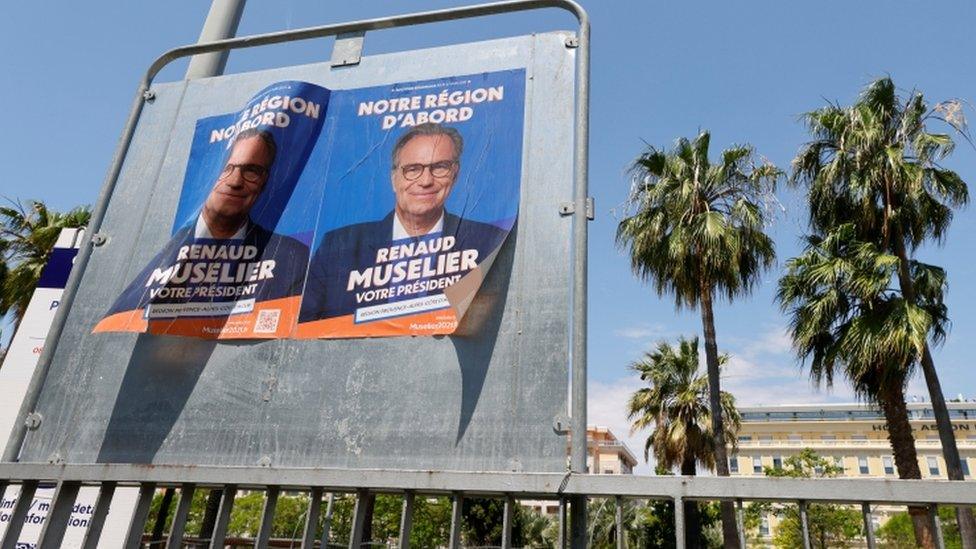

Centre-right incumbent Renaud Muselier has warned that the party's new image is a front and that Mr Mariani is a "Trojan horse".

In a TV debate with Mr Mariani this week, he called his rival and former colleague a "puppet" and said he was being manipulated by the far right.

Adding to the sensitivity, the government last month announced that President Macron's party, La République En Marche, would not be running its own list of candidates for the elections in PACA, but would instead be lending its support to Mr Muselier.

The president's party has thrown its weight behind the Republicans' candidate Renaud Muselier

The National Rally are making the most of it.

"Real" right-wing voters were being turned off the centre right, Thierry Mariani told journalists this week, by a list of candidates that was "more and more the list of Macron".

Difficult vote for Macron's party

France's governing party is contesting its first regional election. Formed just five years ago, it so far has few roots at the local level. Polls suggest it's possible that La République En Marche won't win a region at all.

"We're new," said Marlène Schiappa, the minister in charge of citizenship who is the party's top candidate in Paris. "We don't have officials already elected, yet we're always second or third in the polls. We're on an upward trajectory."

Marlène Schiappa argues that France's political mainstream should unite against the far right

Alliances made sense in some places, she told us, and given the threat posed by the far right, France's traditional parties should "ally to form a collective block against [them]".

The National Rally is currently predicted to win around 40% of the vote here on Sunday.

That's pretty much the score it won in the first round of the last regional elections in 2015, only to be defeated in the run-off by other parties working together to keep them from power.

Could Le Pen shatter 'glass ceiling'?

The pattern is so familiar to the National Rally that pollsters have nicknamed it their "glass ceiling".

But some believe that glass ceiling is now starting to fracture, as voters demand change, and concerns over security and immigration increase.

"For a long time, a vote for the National Rally was a vote of protest against mainstream parties," says Jean-Philippe Dubrulle of the Ifop polling agency.

"That's changed since Emmanuel Macron's victory [in 2017] erased mainstream parties. Now you have a situation where, if you don't agree with Mr Macron - and a majority of French don't agree with him - the most efficient way to express that is to vote for Marine Le Pen."

President Macron was slapped in the face on a visit to south-eastern France earlier this month

At least one of the stallholders in the market thinks it's all over-stated. "There's always talk around election-time of a win for Le Pen, but it never actually comes," he told me, declining to give his name.

"People say they're going to vote for them now, but at the last minute they won't. We have bad memories of the party and its racist past."

If he's right, that's a change in itself. It used to be the case that Le Pen supporters were shy of sharing their intentions, while voting for her in private.

The first signs of how much really has changed will come on Sunday, but the proof will have to wait for the run-off in a week's time.

The whole point of a glass ceiling is that you can't see it. Until it's tested, it's not easy to see when it's gone.

Related topics

- Published21 May 2021

- Published5 May 2021