Bridget Coll: Catholic nun was lesbian, militant and a history maker

- Published

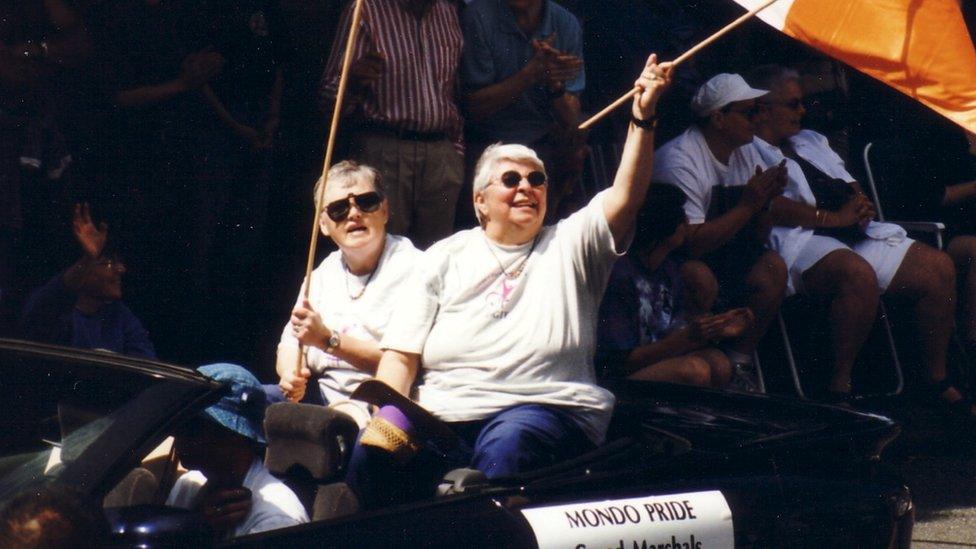

Grand Marshalls of Vancouver Pride in 1999: Bridget Coll and Chris Morrissey

Catholic nun, gay and militant. Bridget Coll, Irish born but a proud Canadian, was a trailblazer.

She and her partner, Chris Morrissey, made history when they challenged Canadian immigration law which had only recognised heterosexual married partners.

As nuns in the 1980s, they stood with the oppressed in Chile against dictator Augusto Pinochet's regime.

Hers is an inspirational journey. She travelled thousands of miles in just one lifetime.

Now, her story features in a new exhibition in Dublin telling the stories of Ireland's LGBTQ+ diaspora.

Bridget Coll recorded the story of her life in 2009

Bridget died in 2016. Her life partner, activist and former nun, Chris, survives her.

Historian Dr Maurice Casey, who curated the exhibition, came upon their story by chance. He had set out to celebrate an LGBTQ+ history of the Irish emigration story.

He was researching the Canadian LGBTQ+ community and was inspired by a series of tapes held by Simon Fraser University, external recorded in 2009, through which the women tell their story.

There is wit and wisdom, a generosity and a humility about Bridget Coll that shines through on the tape recordings from 12 years ago.

She talks about how she was born in Donegal in 1934, one of 12 children from a Catholic family who grew up near Fanad lighthouse. She never questioned her sexuality.

"I didn't even know that queer existed," she said.

At 14, she wanted to be a nun and at 16, joined an order in England.

From there, she went to America to work for the Franciscan Missionaries of St Joseph.

That was where the first seeds of dissent were sown.

"There was an encyclical on birth control from the Pope. The priest gave a whole sermon from the pulpit about how it was a real bad thing to do," she said in the recording.

"I had a lot of contact with mothers of kids that I taught. They would come and tell me their stories about birth control. I listened to the women's stories and their hardships.

"For the first time in my life, I began to doubt the teachings of the Church."

She was drawn to read more about social justice and liberation theology - a radical movement that grew up in South America as a response to the poverty and ill-treatment of ordinary people.

The Liberationists said the Church should act to bring about social change and should ally itself with the working class.

Bridget Coll and Chris Morrissey pictured at the recording sessions in 2009

It was at that time that Bridget became close to Chris, a Canadian nun in the same order.

When Bridget's parents died within weeks of each other in 1977, Chris was the one person who truly helped.

"She said she was a lesbian and asked: 'Do you know what that is?' I said: 'No'.

"She said: 'I think you're a lesbian'. I didn't know the word - that was the first time I knew.

"It was 1977, I was 43, that's the first time I ever heard it and the first time I fell in love with a woman."

Bridget knew she wanted to work in Chile and asked her superior to go there.

"Remember you're going to preach the gospel, not to meddle in politics," she was told.

Chris went with her to Chile in 1981. They lived in a shack in a shanty town joining whatever struggles people were experiencing.

'How distant I was'

They encouraged women to stand up for themselves in a strongly patriarchal society, and got the name of "home wreckers" for it, Bridget joked.

They joined an anti-torture movement. They never knew the second names of the other members - if they were tortured then they could not reveal names.

One day, a letter came from their religious superior. The order was celebrating an anniversary with a garden party.

How would they celebrate in Chile? There was a big protest against Pinochet that day; Bridget and Chris joined it.

"I realised how distant I was from them [the Order]," she said.

After much soul searching, the women left their congregation in 1989 and headed for Vancouver to live openly as a couple.

But Chris could not sponsor Bridget as a Canadian immigrant because they were lesbians. In 1992, she initiated a constitutional challenge, and won.

Bridget Coll and Chris Morrissey feature on a panel in the exhibition

"It was on the local news at six o'clock, then it was on the national news that evening... it was something about Gorbachev first and then these two lesbians in Vancouver," said Bridget.

The women campaigned for LGBTQ+ rights.

'She always loved me'

Chris Morrissey has loving memories of her partner, and says she must listen again to those tape recordings Bridget made in 2009.

She remembers their first protest in Chile. They had to be fast. It was dangerous.

Speaking to BBC News NI from her home in Vancouver, Chris recalls Bridget urging them to get there quickly.

"The protest lasted only three minutes. She was always in the front row. I was the one holding back. She was out in front dragging me along."

The decision to leave their order was huge, says Chris.

"Our whole understanding of faith and spirituality had changed after the years in Chile. There was no way we could go back and listen to a priest preaching," she says.

"I have no regrets… I still value our history and how we learned to be in the world."

The women went on to work for the oppressed and marginalised in Canada.

Then Bridget got dementia.

"Even when she was not quite sure who I was, I could tell by the way she looked at me that she loved me," says Chris.

"She had always loved and stood by me, no matter what. She pushed me from behind and pulled me along.

"At the end of her life, she was content. She died as she lived, simply and courageously."

Dr Maurice Casey presenting Out in the World: Ireland's LGBTQ+ Diaspora at Epic, The Irish Emigration Museum.

Maurice Casey says the couple belong to that "first generation to grow old and out".

"Bridget Coll's story shows that there is an LGBTQ+ story in almost every strand of Irish emigrant history," he says.

The couple showed enormous foresight, bravery, courage, principle and humility, Mr Casey adds.

"They phrase it as though they put one foot in front of the other. But it required an enormous capability."

Canada claims Bridget Coll and Chris Morrissey as part of their country's history, he says, now Ireland should claim them too.