Hungary's anti-gay law threatens programming of TV favourites

- Published

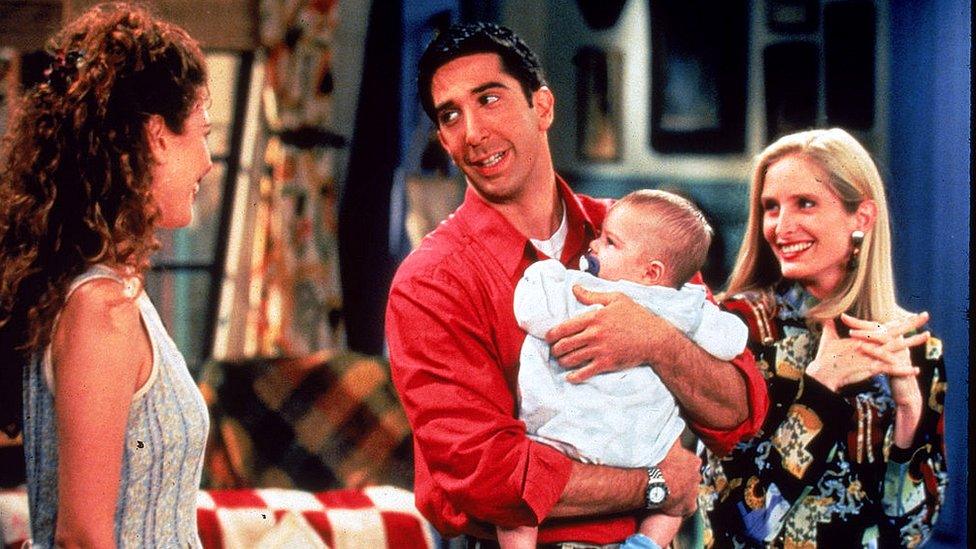

According to popular channel RTL Klub, episodes of Friends could be restricted by the new law

There is growing international condemnation of a Hungarian law that bans the depiction or promotion of homosexuality to those under 18. The controversy surrounds a single paragraph in an otherwise widely backed law against paedophiles, passed by the Hungarian parliament on 16 June.

What will it mean?

Broadcasters, advertisers and school teachers are trying to understand how the law will work in practice.

Popular commercial TV channel RTL Klub says it may have to show some of the Harry Potter films, Bridget Jones Diary, and episodes of Friends after the 22:00 watershed. "Series like Modern Family would be banned," said RTL. Programmes here are categorised in six categories and the channel believes these programmes would end up in category five, along with films such as Billy Elliott and Philadelphia, as they could be seen as either portraying or promoting homosexuality.

In Hungary, the government-appointed Media Authority oversees programme content, labelling and broadcast times and has its own power to investigate, or respond to complaints from the public.

The law disregards freedom of speech by restricting homosexuality in the media and prohibits minors from watching different gender identities in programmes, films or even adverts

Who has spoken out?

Fourteen EU governments including France, Germany, Spain and Ireland have condemned the new law as a "flagrant form of discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender identity and expression". The UK has also spoken out against it. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen says it will be examined for any breach of EU law.

Hungary's footballers play their final Euro 2020 group game in Munich against Germany on Wednesday evening and Mayor Dieter Reiter had planned to light up the Allianz Arena in rainbow colours as a gesture of solidarity.

The Allianz Arena has been lit up in rainbow colours before, but Uefa will not sanction the move for Euro 2020

However, European football's governing body Uefa put paid to that idea. "Thank God, common sense prevailed among European football chiefs," said Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto.

Viktor Orban's ultra-conservative government has hit back against the international outcry, insisting the law only aims to protect children,. "The liberal steamrollers are once again at work against Hungary," said the prime minister.

Is it curtains for Harry Potter?

A former member of the Media Authority suggested that the idea of stopping young people watching Harry Potter or Bridget Jones movies was far-fetched.

"I wouldn't expect much trouble for the broadcasters. For the government, it was a very important symbolic message to send out to the Hungarian public, alongside all their previous pro-family decisions," Andras Koltay told the BBC.

Only if the film was "dominated" by a sex-change or a homosexual theme might the new law be applied, he suggested.

Is the law popular?

The Fidesz government champions conservative family values, and the new law is the latest thread in a tapestry of laws reinforcing the traditional family and stigmatising same-sex relationships.

Late last year, another parliament in effect banned same-sex couples from adopting children, by saying only married couples could adopt, with some exceptions.

Despite this, an Ipsos public opinion survey earlier this year suggested that 46% of Hungarians accepted same-sex marriage - up from 30% only eight years ago.

Hungarian national team goalkeeper Peter Gulacsi spoke out recently in support of more tolerance for "rainbow families".

Hungary's national goalkeeper Peter Gulacsi has spoken out in favour of love, acceptance, and tolerance

Civil rights groups have also been buoyed by a wave of support, including two sizeable demonstrations against the law, and by the outpouring of international solidarity.

Why change the law now?

A less visible target of the law is the Hungarian opposition.

With only nine months to go until the next Parliamentary election, an alliance of six opposition parties from the leftist Socialists to the right-wing Jobbik party are selecting joint candidates to run against Fidesz.

MP Agnes Vadai, who is vice-president of the Democratic Coalition party, says it's a trap for the opposition. She and her colleagues believe the government's aim was to rally its own supporters and divide its opponents. Jobbik MPs voted with Fidesz to approve the law.

"As a right-wing party, we felt duty bound to support the anti-paedophile section of the law," Jobbik leader Peter Jakab told the BBC. "The opposition parties, like our voters, are multicoloured. We all know we can only get rid of this government if we maintain that diversity."

Ms Vadai says they will continue to work together closely: "And when we get into government, hopefully next year, we all agree on the need to change the law, and delete the homophobic elements."

Is Hungary copying Putin?

Parallels have also been drawn between the new Hungarian wording and a 2013 law passed in Russia, which also provoked an international outcry. But legal scholar Andras Racz has pointed to several differences that make the new Hungarian law tougher.

Viktor Orban in London in May 2021: I'm anti-immigration but not anti-Semitic

While the Russian one condemned "non-traditional" sexual relations, the Hungarian version specifically mentions homosexuality. The Russian legislation did not juxtapose homosexuality with paedophilia.

Notably missing from a law that targets paedophiles is any reference to children as victims, or to the problem of paedophilia in the Hungarian Roman Catholic Church. The Church receives large sums from the government and often functions as its close ally.

An investigation by journalist Peter Urfi in 2019 uncovered 17 suspected cases over 20 years, none of which led to a criminal conviction. In most, the priest or Church official in question was either moved to another parish, or quietly retired.

Related topics

- Attribution

- Published22 June 2021