Irish language: 'We need to ensure the Gaeltacht survives'

- Published

About 27,000 students usually attend language courses in the Gaeltacht

A first kiss, a lifelong friendship forged or an introduction to County Donegal's infamous pink burger sauce.

For many young people, spending long summers studying Irish at a Gaeltacht college is an experience that goes far beyond learning a language.

About 27,000 students normally attend Gaeltacht courses in the Republic of Ireland each year - including thousands from Northern Ireland.

But Covid has led to their cancellation for the second year in a row.

It has been described as a massive social and economic blow to the isolated rural communities and some now fear irreparable damage could be caused to the tradition of summer Gaeltacht courses.

Hundreds of local households usually provide accommodation for visiting students and the money they receive for doing so can be essential income for families.

'A way of life'

In west Donegal, Máire Ní Choilm has worked as a bean an tí - the Irish name given to residents who take Gaeltacht students into their homes - for more than 30 years.

She said money from students for food and board is the sole source of income for many people in her profession.

"Round here there wouldn't be a lot of employment and for a long time it's been a way of life to give accommodation to students," she said.

"As a bean an tí I know a lot of us depend on this income all summer."

Ms Ní Choilm said many local families would use the money they made to put their own children through college.

"We weren't entitled to PUP (Pandemic Unemployment Payment) so some people had to go and look for employment elsewhere, retrain or rent their houses as AirBnBs," she said.

While she is optimistic the Gaeltacht colleges will be up and running again by next summer, Ms Ní Choilm said she was "very fearful" another year of cancellations could spell the end of her community's way of life.

"Next year is a case of do or die I would say," she added.

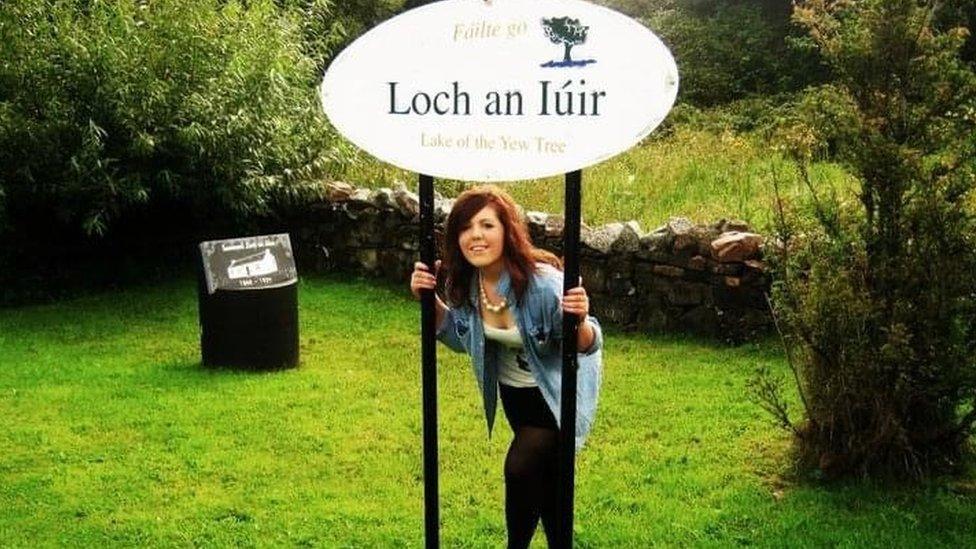

Órla McGurk during her time as a Gaeltacht student

For many Irish language speakers, studying at the Gaeltacht is an essential part of their cultural and linguistic development.

Órla McGurk, an Irish language teacher from Belfast, fell in love with the Gaeltacht in Donegal when she was a teenager.

She said the immersive environment was hugely important in developing her fluency with the language.

"People always ask me how I learned Irish so well and I solely put it down to my time in the Gaeltacht," she said.

"My Irish was learned there, not in school."

'Such a special place'

Ms McGurk said studying in the area when she was younger formed a strong part of her identity.

"You feel like you're a part of something - you're able to form new friendships, go to céilí dances and learn new songs," she said.

"Back then we didn't have internet on our phones - in the Gaeltacht we were cut off from social media and things like that. But you didn't miss it, you just made your own craic."

But she is also worried for the future of language studies in the area.

"I felt so anxious about it whenever lockdown started - it's such a special place for me," she said.

"When I have kids I want them to go to the Gaeltacht and be immersed in the language, I want them to have the same experiences as me.

"But if no money is coming in to the local economy, who knows if they're going to open again?"

"We depend on the summer to keep us going through the winter months"

Many small businesses in the Gaeltacht depend on trade from visiting students and their families.

Dominic Sweeney runs a ferry service to Arranmore Island, home to Coláiste Árainn Mhóir Irish language college.

About 360 students usually cross over to the island by ferry to study during the summer, but Mr Sweeney said this trade has been "wiped out" by the pandemic.

"We've had no visitors at all really," he said.

"Along with the students you had all of the suppliers - the butchers, bread vans, supermarket suppliers - that used to keep all those houses going."

Hundreds of visiting parents are also a massive boost to ferry traffic.

Mr Sweeney said government wage subsidies for his part-time staff have helped, but the loss of visiting students and their families has been very difficult to absorb.

"We always depended on the summer to keep us going through the winter months - we still have a full crew and two boats to maintain," he said.

Socially and economically deprived area

The Irish government has provided grants totalling about €240,000 (£203,000) for Gaeltacht community halls, where college classes and events are usually held.

More than €2m (£1.6m) has also been set aside for college accommodation providers.

But west Donegal councillor Michael Cholm Mac Giolla Easbuig said this is not enough and has called for further intervention from governments on both sides of the Irish border.

Speaking to BBC News NI, he said it was "well known" that the west coast of County Donegal is a socially and economically deprived area.

He said the absence of students there for a second year was not only an economic blow to the community but also "a massive social blow".

"It's vital that Stormont and the Dublin government put a proper financial package in place, just for a year or two, to ensure we don't lose what is very dear to the locals and to the student population," he said.

"The community is missing the students. It's far more than just a language experience - we need to ensure the Gaeltacht survives."

Related topics

- Published7 May 2021

- Published13 August 2015