Afghan crisis: Russia plans for new era with Taliban rule

- Published

Russia's key concerns are regional stability and border security for its Central Asian allies

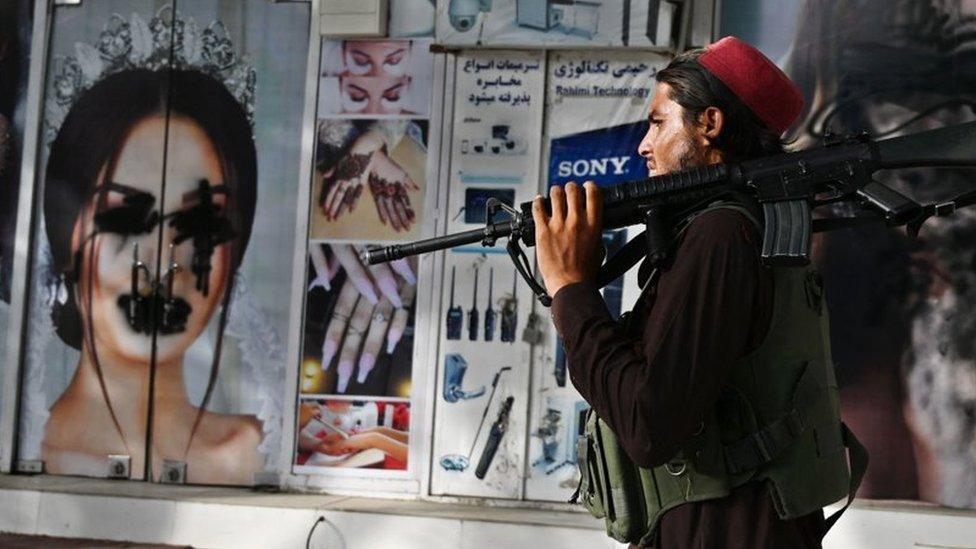

When US and European governments raced to get their citizens and Afghan colleagues out of Kabul this week, Russia was one of very few countries not visibly alarmed by the Taliban takeover.

Russian diplomats described the new men in town as "normal guys" and argued that the capital was safer now than before. President Vladimir Putin said on Friday that the Taliban's takeover was a reality they had to work with.

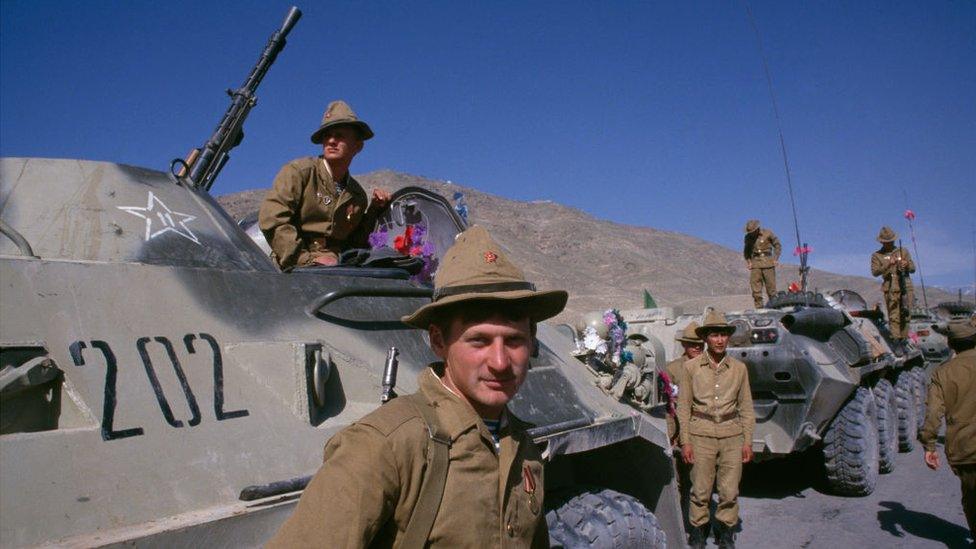

It is all a far cry from the disastrous nine-year war in Afghanistan that many Russians remember from propping up Kabul's communist government in the 1980s.

Warm words for Taliban

Unlike most foreign embassies in the capital, Russia says its diplomatic mission remains open and it's had warm words for the new rulers. Ambassador Dmitry Zhirnov met a Taliban representative within 48 hours of the takeover and said he had seen no evidence of reprisals or violence.

Moscow's UN representative Vassily Nebenzia spoke of a bright future of national reconciliation, with law and order returning to the streets and of "the ending of many years of bloodshed".

Russia's special Afghanistan envoy (R) has been talking to Taliban leaders for some years

President Putin's special envoy to Afghanistan, Zamir Kabulov, even said the Taliban were easier to negotiate with than the old "puppet government" of exiled President Ashraf Ghani.

Moscow has had little time for Mr Ghani: its diplomats claimed this week he had fled with four cars and a helicopter full of cash - accusations he dismissed as lies.

Charting Russia's improving ties

Russia is not racing to recognise the Taliban as Afghanistan's rulers, but there has been an apparent softening of rhetoric. State news agency Tass this week replaced the term "terrorist" with "radical" in its reports on the Taliban.

Moscow has been building contacts with the Taliban for some time. Even though the Taliban have been on Russia's list of terrorist and banned organisations since 2003, the group's representatives have been coming to Moscow for talks since 2018.

Russia has not yet recognised the Taliban as Afghanistan's new government

The former Western-backed Afghan government accused Russia's presidential envoy of being an open supporter of the Taliban and of excluding the official government from three years of Moscow talks.

Mr Kabulov denied that and said they were ungrateful. But as far back as 2015 he said Russia's interests coincided with the Taliban when it came to fighting Islamic State (IS) jihadists.

That did not go unnoticed in Washington. US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson accused Russia in August 2017 of supplying arms to the Taliban, a remark that Moscow rejected and described as "perplexing".

The foreign ministry in Moscow said it had "asked our American colleagues to provide evidence, but to no avail… we do not provide any support to the Taliban".

In February this year, Mr Kabulov angered the Afghan government by praising the Taliban for fulfilling its side of the Doha agreements "immaculately" while accusing Kabul of sabotaging them.

Focus on regional security

Despite its closer ties with the Taliban, Moscow is for now staying pragmatic, watching developments and not removing the group from its terror list just yet. President Putin said he hoped the Taliban would make good on its promises to restore order. "It's important not to allow terrorists to spill into neighbouring countries," he said.

The key factors shaping Russia's policy are regional stability and its own painful history in Afghanistan. It wants secure borders for its Central Asian allies and to prevent the spread of terrorism and drug trafficking.

When the US targeted the Taliban after the 9/11 attacks and set up bases in former Soviet states in the region, Russia initially welcomed the move. But relations soon grew strained.

Earlier this month Russia held military exercises in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, aimed at reassuring Central Asian countries, some of which are military allies of Moscow.

Last month Russia obtained Taliban assurances that any Afghan gains wouldn't threaten its regional allies and that they would continue to fight IS militants.

Russia's bitter memory of war

Russia stresses it has no interest in sending troops to Afghanistan, and it is not hard to see why. It fought a bloody and, many would argue, pointless war there in the latter years of the Soviet Union in the 1980s.

Vladimir Semochkin served in Afghanistan in 1987-1989

What began as a 1979 invasion to prop up a friendly regime lasted nine years and cost the lives of 15,000 Soviet personnel.

It turned the USSR into an international pariah, with many countries boycotting the 1980 Moscow Olympics. It became a massive burden on the crumbling Soviet economy.

While the Soviet Union installed a government in Kabul led by Babrak Karmal, the US, Pakistan, China, Iran and Saudi Arabia supplied money and arms to the mujahideen, who fought the Soviet troops and their Afghan allies.

The Soviets were eventually forced to leave Afghanistan after a guerrilla campaign by mujahideen

Many of those killed were teenage Soviet army conscripts, and the war drove home a realisation of just how little the Soviet authorities cared about their own people. The war is widely thought to have hastened the end of the Soviet Union, at least in part, by stirring disillusionment with its rulers.

The war ended with an ignominious military withdrawal in February 1989.

Many Russians have painful memories of the nine years spent fighting a war in the final years of the Soviet Union

Fears for the future

Russia may have given the impression of being prepared for the Taliban's sweep to power, but some experts believe Moscow was taken by surprise as much as everyone else.

"We cannot talk about any strategy from Moscow," says Andrey Serenko from the Russian Centre for Contemporary Afghanistan Study who sees decision being made on the hoof. "Moscow is worried about being late to the reshaping of the regional architecture."

Others in Moscow are wary of what Taliban rule might bring.

Andrei Kortunov, head of the Russian International Affairs Council think tank, believes they will struggle to control the entire country, especially the north, and that could threaten Russia and its neighbours.

"Perhaps, some cells of al-Qaeda, perhaps of Isis, based in Afghanistan, would instigate some actions in Central Asia," he says.

He also fears a sharp deterioration in the Afghan economy, which could in turn prompt further instability.

Related topics

- Published19 August 2021

- Published20 August 2021

- Published20 August 2021