'I'll be at front of queue to change my slave name'

- Published

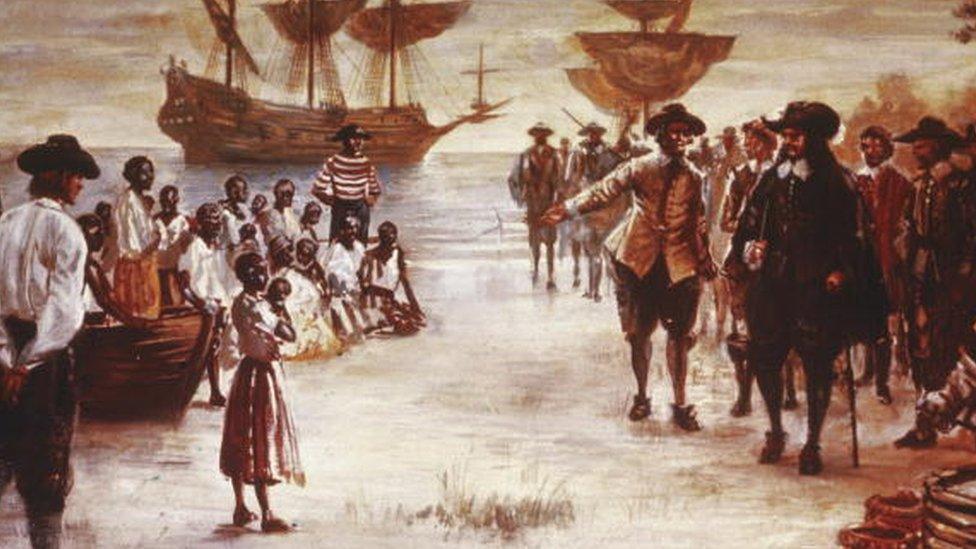

For more than three centuries the Dutch shipped more than half a million Africans across the Atlantic

Descendants of African slaves have told the BBC they will change their surnames, after a Dutch city decided to make the procedure free of charge.

Utrecht council has decided to remove the €835 (£715) cost and bureaucracy to help people shake off their "slave names" and have the option to adopt one that recognises their African ancestry.

Under existing Dutch rules, if you have a surname considered ridiculous such as Anus, Garlic or Naked-born, there is no requirement to prove it is undesirable. However, if your name has its origins in the Dutch colonial legacy, an expensive psychological examination is often required on top of the fee.

"It's not right to then ask for money to turn back the procedure," says Linda Nooitmeer, chair of the national institute for Dutch slavery history.

Her own name translates as Never Again. Even though she's relatively happy as it was chosen by her ancestors, she is thinking of changing it. She sees Utrecht's move as "part of the healing process, to give people the freedom and identity back".

Three centuries of slavery

Between 1596 and 1829 the Dutch shipped more than half a million Africans across the Atlantic Ocean to work on plantations.

They were treated as objects and possessions and their names were erased, part of what Linda Nooitmeer describes as the "dehumanising" process.

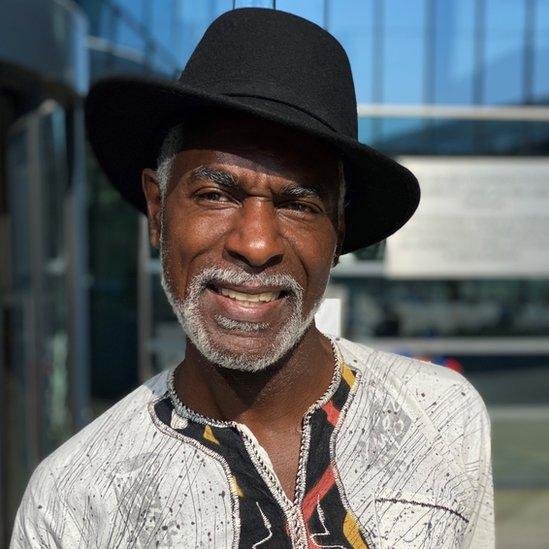

Guno Mac Intosch welcomes the chance to change his name officially to Yaw

"Everything is stripped. You were part of the cargo, like cattle. It's not only the name, but rituals, language, your identity, all evidence that you were African was taken away."

The Netherlands was one of the last countries to abolish slavery in 1863, 30 years after British abolition. Even then slaves in Suriname, on the north-east coast of South America, had to wait 10 years to be fully free. Slaves were also shipped to Brazil, as well as Haiti, Curaçao and elsewhere in the Caribbean.

Anyone enslaved in Suriname had to be on a slave register, so it is known that some 80,000 people lived in slavery there in the 30 years before abolition.

Stigma for descendants

Freed slaves were given artificial names, often tied to the slave owner, the plantation or random amalgamations of Dutch cities or Dutch-sounding words, although regular Dutch surnames were banned.

Dutch ships transported slaves across the Atlantic for more than 200 years

Berghout and Seedorf were used as was Madretsma (Amsterdam spelt backwards) and Eendragt, a plantation name that means harmony. Other names translate as Obedient, Cheap, Tame and Submission.

Linda Nooitmeer believes these names serve as a reminder they were once subordinate, and that the chain was never fully relinquished.

Hundreds express interest

With that link to their ancestral home long destroyed, many have gone in search of their African roots to find a name that better represents who they are.

Among them was Yaw, who went to Ghana. And now Utrecht is removing the cost, he plans to make Yaw official, replacing his existing name Guno Mac Intosch.

"As soon as that door opens," he gestures to the city hall, "I'll be at the front of the queue."

Last year almost 3,000 people opted to switch their surnames, but only one mentioned colonial connotations. Utrecht's promise to cancel the fee and paperwork has already resulted in hundreds of expressions of interest.

"Maybe it's not the exact same name our ancestors had," Ms Nooitmeer explains, "But it was given within the spirit from Africa. And that's really powerful to give your children and descendants." Their names are an integral part of their identity, she says.

From the 600,000 enslaved who came from Africa and went to Curaçao, Suriname, and all the other islands, after slavery, there were 60,000 left.

After emancipation, some created collectives and bought the cotton fields.

For them, adopting a new name was an act of empowerment, as the owned became the owners. Ms Nooitmeer believes they would have understood why their descendants were trying to rediscover what she calls their African energy.

A slavery exhibition was recently held at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, curated by its head of history, Valika Smeulders.

The Rijksmuseum recently hosted an exhibition entitled "Slavery"

We meet in The Hague's historic centre, in Lange Voorhout, which she explains was built on wealth generated by the slave trade.

Ms Smeulders is of mixed-race and descended from the slavers, slavers and contractors. Their surnames include Dutch, Scottish, and Portuguese names and she considers her ancestry "very much colonial history". For her, changing a surname is a complex, personal choice and unlikely to create an immediate rush among as many as one million people in the Netherlands.

"People react very differently to circumstances. So for some, [their name] might be something that they want to embrace," she explains.

This is part of who I am, and I don't let my circumstances dictate who I am. For other people, it could be so painful that they want to get rid of it and start afresh

Many people who have a Dutch name plan to keep it, because numerous studies have shown a foreign-sounding name in the Netherlands can expose you to discrimination in education, housing or employment.

Yaw's son pointed out that the Scottish name Mac In Tosch probably opened doors in his corporate life.

Sitting in the shadow of the slave memorial in Amsterdam's bustling Oosterpark, Linda Nooitmeer remembers the moment Mayor Femke Halsema apologised for the council's role in the slave trade.

"It really did something to me. I would never have imagined that even four years ago, never. So we're making steps."

As I speak to Yaw outside Utrecht city hall a man comes over shouting racial abuse: "You're not African, just because you're black. If you think you are African, go back! Coming here for our benefits."

People glance up until another white man intervenes.

It is a shocking moment but Yaw takes it in his stride. For him the Netherlands is still on a journey and the recognition of people's desire to drop their slave names represents a small but significant step.

Earlier this year Amsterdam Mayor Femke Halsema formally apologised for the city's role in slavery

"Dutch people claim that they are really liberated and the country is liberated, then you see these things, this behaviour," he says.

The world-wide Black Lives Matter movement has made a difference, he believes, and the name-changing move is part of a process that shows greater awareness.

"We are here, we built this country, and we don't let people chase us away because they say that we do not belong here."

You may also be interested in:

BBC News presenter Clive Myrie visits Bristol and explores its colonial legacy

Related topics

- Published17 June 2021

- Published1 August 2020