Igor Kirillov: TV man known as the face of the USSR dies at 89

- Published

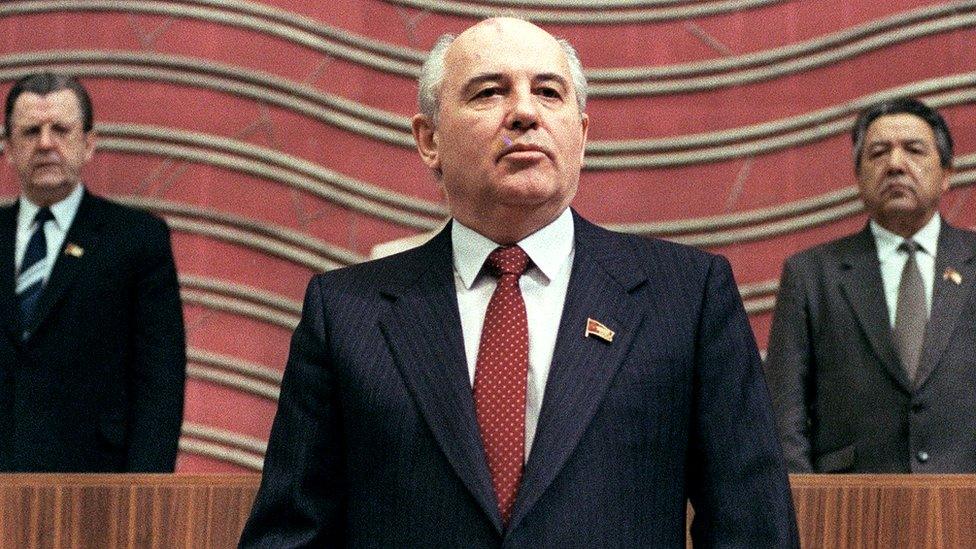

Igor Kirillov (right) was given the Order of Honour by Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2018

Igor Kirillov - the man known as the face and voice of the USSR for three decades - has died in Russia aged 89.

Kirillov was Soviet TV's chief newsreader and announcer.

With his trademark delivery - unhurried and calm - he informed viewers of the first sputnik in space, and delivered the communiqués of the Communist Party.

He also anchored all major Soviet set-piece events: from Moscow's Red Square parades to communist congresses. The Soviet Union collapsed in 1991.

Positive stories dominated Soviet news bulletins. Every year, to images of combine harvesters advancing through the fields, Igor Kirillov would declare the grain harvest a triumph.

But did he believe it?

"For me the hardest thing of all was to believe what I was reading out," Igor Kirillov told me in an interview in 2011.

"Deep down I knew that the texts contained half-truths. But as a newsreader you had to convince yourself it was the complete truth. And I did. I persuaded myself that we really were building communism. That life really would get better. Any doubts I had I managed to overcome. If I hadn't then I wouldn't have been able to do my job."

The news wasn't always good.

In the 1980s Soviet leaders got into the nasty habit of dying in rapid succession. It was a sombre Igor Kirillov who informed the country of their passing.

It happened so often, in fact, that it sparked this famous Soviet joke: Igor Kirillov goes on air in a black tie and announces: "Comrades, you're going to laugh, but another irreplaceable leader needs replacing."

He had trained as an actor. So how did he break into television?

Journalists 'read too fast'

"At the job interview, I played the guitar and sang," he told me. "Then they asked me to read something out. Luckily the night before I'd memorised a copy of the newspaper Pravda. So I recited that, right off the top of my head. Afterwards as I was leaving the building, the chief stopped me. 'Where are you going?' he said. 'You've got the job and you're on air in two hours'."

The communist newscaster had other jobs, too. He presented Soviet TV's version of Top of the Pops. It was a little more Lenin than Paul McCartney.

In 1985 he became a global chart-topper, with a little help from Sting, whose hit song Russians kicks off with Igor Kirillov's voice reading the news.

By the late 1980s television news was changing around the world. Journalists were replacing professional announcers as newsreaders. The USSR was no exception. Soviet TV revamped its nightly news. In came reporters… out went the "dyktory".

In 1990, during a study year in Moscow, I interviewed Igor Kirillov for a university project. The Soviet Union's most famous announcer was having a difficult time.

"I read the news for 20 two years on the nightly news Vremya," he told me. "Now they've decided not to use 'diktory'. There's a condescending, disdainful attitude now towards announcers."

He thought that journalists who became anchors delivered the news too fast.

"Russians don't like fast talking. They have their own way of conversing: in a calm, unhurried, thoughtful way.

"If TV news goes in one ear and out the other, our heads will be empty."

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Related topics

- Published31 October 2013

- Published13 December 2016