Channel tragedy: Scramble to identify dead off Calais

- Published

It is now known that 17 men, seven women and three children died

At least 27 people died on Wednesday in the worst-recorded migrant tragedy in the Channel and French officials are trying to identify who they were.

Only two people survived, a Somali and an Iraqi, according to French Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin. He said they were recovering from extreme hypothermia and would be questioned in due course.

But little is known of those who did not survive when their inflatable boat lost air and took on water off the northern port of Calais.

Among the dead were 17 men, seven women and three children, prosecutors in Lille told the BBC. Calais Mayor Natacha Bouchart said one of the women was pregnant, while one of the children was a "little girl".

Forensic investigations are under way but no one has yet been named.

Many of them had travelled to France from the Middle East, unconfirmed reports suggest. The BBC has spoken to several charities, who said many of the dead appear to have been Kurds from Iraq and Iran. Some may have been Arabs and Afghans, as well as other Iranians.

Masrour Barzani, prime minister of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, said the tragedy was a potent reminder of the dangers of "illegal migration and the smugglers who send people to their deaths".

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Handa Majed, founder of the Kurdish Umbrella charity, said she had been in touch with various sources who were trying to identify those who died.

Based on her research, the majority of them appeared to be Iraqi Kurds, she said, and that was not surprising.

"Young people in Kurdistan don't have any jobs," she said. "There's no prosperity. There's no social support system like in the UK, so if you don't have a job, you could starve to death."

Kurdish journalist Ranj Peshdari, who said he had spoken to people on the ground in France, echoed those initial reports about the backgrounds of the dead.

He told the Rudaw media group that he understood most of the dead had made the journey to Europe from the Kurdistan region.

BBC Newsnight: Lewis Goodall reports from Dunkirk's new migrant camp.

The French interior minister said police were unsure about their nationalities because none of them had identity documents.

"It wouldn't be unusual at all for people not to be travelling with ID documents," said Stuart Luke, a lawyer who specialises in asylum cases involving unaccompanied children.

There were several reasons for that, he told the BBC. Some people lied about their origins to improve their chances of asylum, while others came from countries that had no culture of carrying identity documents, he said.

Maya Konforti, who works with Calais charity L'Auberge Des Migrants, said it had become a common problem trying to identify fatalities in the Channel.

Identifying the dead is often a complicated process

French police did collaborate with charities but it was a long and often complicated process.

Ms Konforti said the families of those who died often had no idea about their fate.

"The families are always in horrible shock to hear about a death," she said. "They know that it's dangerous, but they don't know how dangerous it is."

For migrant charities and NGOs, the circumstances of Wednesday's deaths were grimly familiar, predicted as well as predictable.

Charlie Whitbread works for an organisation called Mobile Refugee Support in Dunkirk, where the boat involved in Wednesday's deadly crossing cast off.

Speaking to the BBC, he said the conditions in the French camps were so horrific, that people there were willing to risk their lives to try to find a better life.

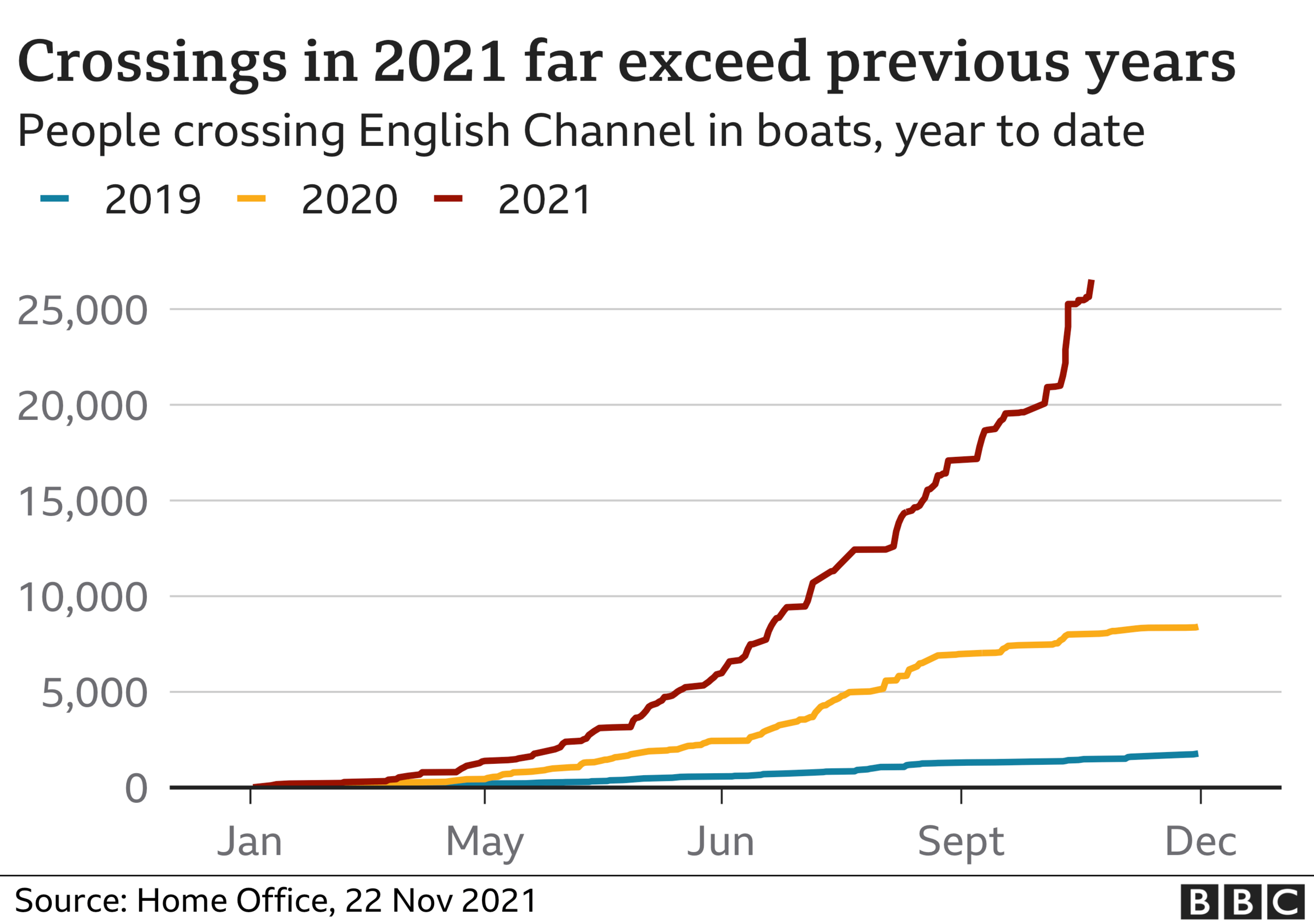

Record numbers of migrants have been making the crossing from France to the UK in recent weeks. More than 25,700 people have made the dangerous journey to the UK in small boats this year - more than three times the 2020 total.

At least 10 other people are thought to have died while attempting to make the crossing in the past few weeks.

Charity workers say poor conditions in French camps are driving people to make the crossing

In migrant camps in Calais, the BBC's Lucy Williamson says Wednesday's tragedy is being met with a sad sort of resignation.

Meanwhile at a camp to the east in Dunkirk, the BBC spoke to some people who claimed to have known those who drowned.

Among them was Juma, who said he fled the Taliban in Afghanistan. He said he wanted to bring his daughters to the UK so they could go to school and study.

He knew some of those who died, he said, and wept quietly as he repeated what they told him: "They said goodbye… I said goodbye. They looked hopeful."

Another Afghan, Sadar, said it was "a very sad day".

He said came to the UK as a child but was denied asylum and told to return to Afghanistan. Now aged 24, Sadar said wanted to come back to the UK and had paid smugglers €3,000 (£2,500; $3,300) to get him there.

Sadar, like many others in French camps, are determined to cross the Channel again, regardless of the risks. For them, it's a risk worth taking.

"We'll try again," said Sadar. "We have two options: we die or we reach the UK."

- Published24 November 2021