Putin-Biden talks: What next for Ukraine?

- Published

A Ukrainian soldier on patrol: Nato and the US are worried about a build-up of Russian troops on the eastern Ukraine border

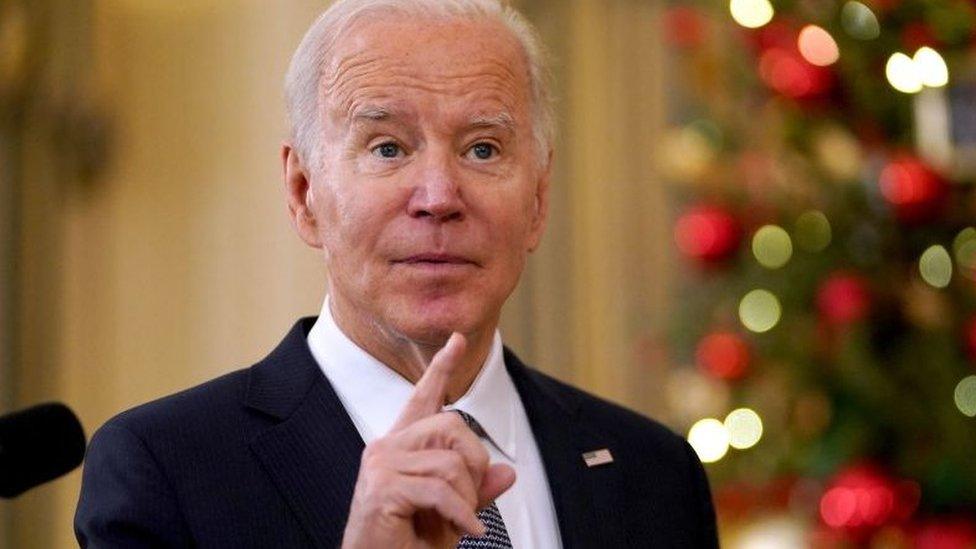

Russian President Vladimir Putin and his US counterpart Joe Biden have held urgent talks as Ukraine fears a Russian invasion. So what happens now, asks Jonathan Marcus of the Strategy and Security Institute, University of Exeter.

Has the video summit meeting between the Russian and US presidents fostered a new diplomatic understanding between them or is Moscow's military threat to Ukraine still very much alive?

One conversation alone will not end this crisis. Everything now depends upon what Mr Putin takes away from this discussion and what signals he receives and sends, in the days and perhaps short weeks ahead.

The seriousness of this situation cannot be over-stated. The scale and nature of Russia's military build-up around Ukraine is extraordinary. US intelligence sources are warning that the Kremlin is preparing for a multi-front offensive, as soon as early next year, involving some 175,000 troops.

Michael Kofman, one of the West's best-informed watchers of Russian military affairs, at the US Centre for Naval Analyses, says people are right to be concerned.

"While the current Russian military posture supports a range of contingencies," he tells me, "what's remarkable about it is the size of the combat elements assembled and the follow-on force designed to hold seized territory.

"Consequently, it looks like a credible invasion force, in excess of anything put together in 2014-2015, (the last time major Russian units were directly involved in the fighting) designed for a large scale military intervention."

So what will the impact of this hastily arranged US-Russia summit be?

In broad terms there are essentially three potential outcomes. Russia might simply back down in the face of the threat of concerted and punitive Western economic sanctions. Or some kind of renewed diplomatic process could be established that averts conflict. Or, perhaps the die is cast.

Maybe Mr Putin has determined that only direct military action can achieve his goals regarding Ukraine, and given western Europe's winter energy woes, President Biden's perceived weakness, and the distraction of the Covid pandemic, now is the best time to strike.

1) Putin backs down

This is perhaps the least likely of outcomes. Mr Putin has marched his troops up the hill and they are not going to return to their barracks without him registering some kind of victory. President Putin has both international and domestic concerns. Perceived weakness will serve him badly.

For all his talk about Russia and Ukraine's historic destiny, which is dismissed by many western commentators as hyperbole, he has real concerns - not just about what he sees as Ukraine's drift into Nato's orbit, but also about the consequences of a viable democratic system being established in what he regards as part of the Russian heartland.

He must of course weigh up the apparent sense of trans-Atlantic unity and the threat of economic sanctions. But Russia has weathered western sanctions before. And he may believe that western unity can be tested to destruction given the energy weapon that Moscow might wield.

2) A diplomatic solution

President Biden is not going to accept Russia's demand for a veto over Ukraine's potential membership of Nato. Though in reality any such membership is a long way off. So could Mr Putin be offered some wider diplomatic benefits to forestall war?

The Russian president has already registered a small diplomatic victory of sorts insofar as this video summit with his US counterpart has happened at all. Russia's ongoing troop build-up around Ukraine has forced the US president to put Moscow's concerns at the top of its foreign policy agenda. It's a potent reminder that for all the talk about Washington's new strategic focus being on China, it cannot ignore its long-standing commitments in Europe and, if Moscow seeks to do so, it can - temporarily at least - re-order the Biden administration's strategic priorities.

Returning to the "superpower" table is a small plus for Mr Putin. But it is unlikely to be enough. Nonetheless the two leaders did begin a renewed dialogue at their summit in Geneva last June. Then, both sides expressed themselves pleased with the outcome.

Russian troop build-up: View from Ukraine front line

This latest meeting touched on other issues beyond Ukraine, some of which were raised in Geneva; the US-Russia dialogue on strategic stability, ransomware, and joint work on regional issues like Iran.

Such discussions are music to Moscow's ears. But how far might they go? Could some kind of renewed or amended diplomatic initiative be conceived for the separatist, pro-Russian areas of eastern Ukraine to replace the largely moribund Minsk II process? This was the diplomatic agreement in 2015 which sought to end the fighting in the Donbas region, involving Russia, Ukraine and the OSCE, with mediation from the leaders of France and Germany.

Might the US itself become engaged in such talks, raising their status? Possibly yes. But this would still not address Russia's fundamental issues regarding the government in Kyiv and Ukraine's overall trajectory.

Michael Kofman believes that a diplomatic solution that forces Ukraine into concessions in return for a Russian troop pull-back is unlikely.

"Undoubtedly," he says, "the Russian preference is to compel Ukraine and the United States to a change in policy; the former on Minsk II, the latter on the current state of defence co-operation and future of Nato expansion.

"Moscow wants the US to agree to a de-facto neutralisation of Ukraine, which would have profound implications not just for the country, but for how security is managed in Europe."

He simply doesn't see this happening, he tells me, "and equally, given the stakes, one struggles to imagine Russian forces retiring from the field having gained nothing politically".

3) Military action

Russia is preparing for the military option whether it happens or not. This could take a variety of forms from a large incursion, to a significant invasion of the eastern part of Ukraine. One aim would be to bring the main fighting elements of the Ukrainian army to battle and to inflict such a defeat upon them that the Kyiv government has to rethink its position.

Invading territory amidst a hostile population has significant risks. Ukraine's armed forces have had some western weaponry and training and are much improved since 2015. However, Russian forces have also improved over recent years. The firepower Russia is building up is impressive. For all the talk about Ukrainian sovereignty Nato cannot and will not come to Ukraine's aid.

And additional weapons supplies might simply contribute to Russia's justification for war.

President Putin in Crimea, which Russia seized from Ukraine and then annexed in 2014

Moscow's calculation of the costs of conflict may also be influenced by previous military deployments. While the West currently sees military engagements through the prism of the strategic defeats in Iraq and Afghanistan, Russia may take a very different view. Its operations in Georgia, its seizure of Crimea, its combat in eastern Ukraine - not to mention its involvement in Syria - may all be seen by President Putin as relative victories.

Of all the military contingencies, Michael Kofman still thinks that if it happens it will be big. "I think Russia is in the best position since 2014 economically, politically, and militarily to execute such an operation, which is not to say it will happen, but simply to suggest that there are the fewest constraints relative to other periods when it has conducted offensive operations."

What to watch for now

The US statement released after the Biden-Putin talks spoke of the two leaders tasking their teams to "follow-up", suggesting that at the minimum, the dialogue might continue and channels remain open.

So what are the chances of avoiding war? And what should we look for that will indicate the imminent outbreak of hostilities?

Michael Kofman notes that "war is a matter of politics, and the signs will largely be political". "The Russian official position is a non-starter in many respects and does not offer room for optimism that an agreement may be reached," he says.

On the military side, while an invasion is not imminent, there are a host of indications and warnings that might be present in the weeks and days running up to any operation. The nature and disposition of Russian forces and their activity is one sign.

For now, Michael Kofman's view is that the tensions will continue. "As it stands, Russia is likely to keep building up forces, and if they intend to commit to this course of actions, back them with the support and logistical elements required for a large-scale operation."

Jonathan Marcus is honorary professor at the Strategy and Security Institute, University of Exeter, UK

Related topics

- Published4 December 2021

- Published15 November 2021