Irish mother and baby homes inquiry 'breached its duty'

- Published

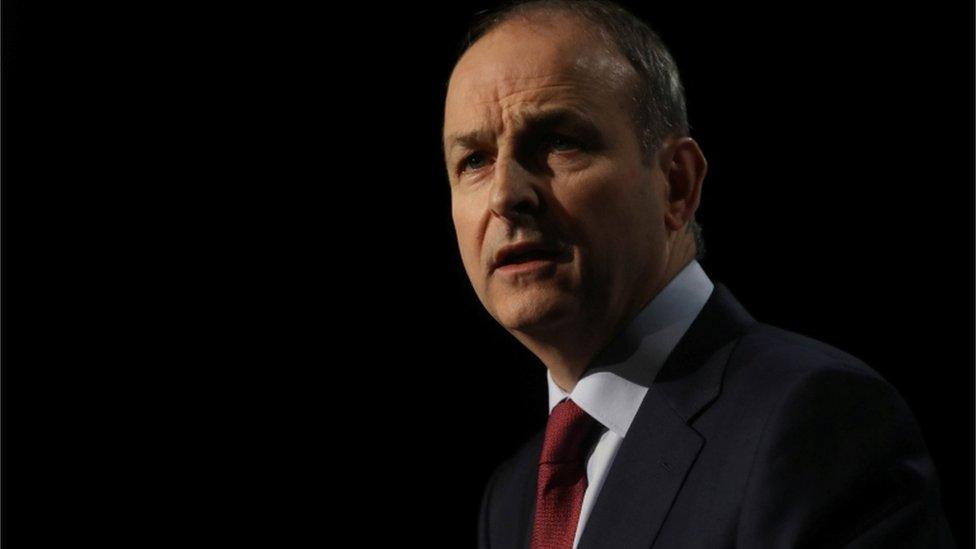

Minister for Children Roderic O"Gorman accepted that survivors were not given the opportunity to challenge what was written about them

The Irish government has accepted that an inquiry into mother and baby homes breached its duty by not giving survivors a draft of its final report.

Eight survivors of mother and baby homes took legal action against the government, having been angered by the inquiry's findings in January 2020.

All eight cases have now been settled.

The government also agreed to publish an "acknowledgement" stating that a number of survivors do not accept the report fully reflected their testimony.

In a statement, the Irish Department for Children said Minister Roderic O'Gorman "has always recognised and accepted the concerns of some survivors about the final report and this written statement formalises that acknowledgement".

The legal action began last year, shortly after the publication of a six-year independent inquiry into Ireland's mother and baby homes.

The institutions were set up to house women who had become pregnant outside marriage, but residents had to endure extremely harsh conditions.

Several former residents told the inquiry that they were kept in the homes against their will, made to work without pay and some testified they were forced into giving up their babies for adoption.

What did the report say?

The commission of inquiry was chaired by judge Yvonne Murphy (centre) who led investigations into clerical child abuse

The final report of the Commission of Inquiry into Mother and Baby Homes concluded there was an "appalling level of infant mortality" in the homes, which it said was likely due to overcrowding; poor hygiene standards and a lack of infection control.

However, the report found "no evidence that women were forced to enter mother and baby homes by the church or state authorities" and "very little evidence" of enforced adoptions.

It outlined the very difficult living conditions endured by residents, but concluded that responsibility for their harsh treatment "rests mainly with the fathers of their children and their own immediate families".

The report said mother and baby homes "provided a refuge - a harsh refuge in some cases - when families provided no refuge at all".

Former residents expressed concern that the testimonies of many witnesses had been largely ignored and fears that the report would become the official history of mother and baby homes.

Who challenged the findings?

Philomena Lee's experience of living in a mother and baby home was turned into a film

Eight people took judicial review proceedings against the government, including the high-profile campaigner Philomena Lee.

Ms Lee became pregnant at the age of 18 and spent more than three years living in the Sean Ross Abbey mother and baby home in Roscrea, County Tipperary.

She gave birth to a son in the home in 1952, but he was adopted by an American family and the pair later spent decades searching for each other.

Her son died before they met, but he asked to be buried in the grounds of Sean Ross Abbey in the hope she would find his grave.

Their story was turned into a book and later into a film starring Dame Judi Dench as Philomena.

Ms Lee was among more than 500 people with "lived experience" of mother and baby homes who agreed to give evidence to an independent inquiry into mother and baby homes.

In April this year, she brought a High Court challenge in an attempt to quash parts of the inquiry's final report.

Ms Lee's lawyer claimed sections of the report directly contradicted Ms Lee's sworn testimony to the commission of investigation, particularly the circumstance of her son's adoption.

Ms Lee argued she should have been given an opportunity to read a draft of the sections relating to her, and to make submissions on them, ahead of the final report.

She said her rights had been breached by the commission's failure to provide the draft.

Other former residents who brought separate, similar challenges included Mary Harney and Mari Steed, who were both born in Bessborough mother-and-baby home in Cork.

What was the outcome?

The High Court in Dublin heard on Friday that the cases had been settled by the government and the women's costs will be paid by the state.

As part of the settlement, Mr O'Gorman will publish an acknowledgement alongside the government's publication of the inquiry's final report.

According to his department, it will state that "a number of survivors do not accept the accounts given in the final report as a true and full reflection of what they said" to the inquiry.

Mr O'Gorman has acknowledged that because the witnesses were not able to view the report in draft form, they did not have the opportunity to ask the commission to correct statements they believed to be wrong.

The minister's statement will "identify key paragraphs of concern to the applicants" and will be published alongside the official online version of the report as well as in the library of the Irish parliament.

The department confirmed that the minister has also consented to a declaration that the commission of inquiry "acted in breach of statutory duty" by failing to provide the applicants with a draft of the relevant part of the report, as required by legislation governing commissions of inquiry.

However, the commission's findings have not been quashed, despite the now officially acknowledged objections of those litigants.

The department added that Mr O'Gorman "appreciates that the findings and recommendations of the commission are important to many survivors".

"While the minister acknowledges that specific paragraphs are not accepted by a number of survivors, he is also aware that some of those paragraphs may reflect the experiences and evidence of other survivors."

Related topics

- Published16 February 2021

- Published13 January 2021