Secret Irish papers reveal scepticism on Troubles decommissioning

- Published

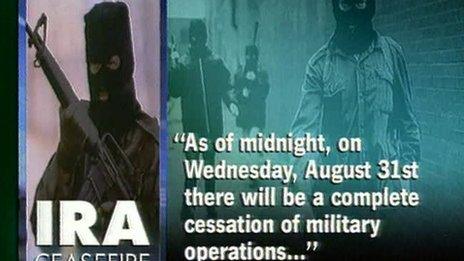

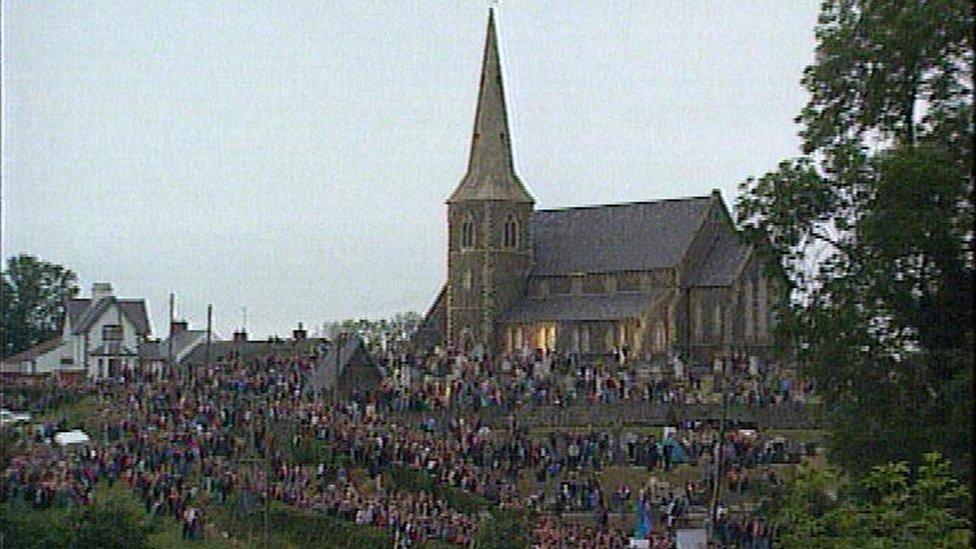

The IRA ceasefire statement as it appeared on BBC television in 1994

Irish state papers covering the build-up to the Good Friday peace agreement have just been published.

The papers span the period of time from 1991 to 1998.

The decommissioning of paramilitary arms dominated the period.

Twelve months after the IRA's 1994 ceasefire, all-party talks on the future of Northern Ireland had not started, much to Sinn Féin's anger.

That was despite suggestions that the US President Bill Clinton might make an historic visit towards the end of November 1995.

Unionist parties and a UK Conservative government led by John Major were insisting on what was called "Washington Three" - the actual decommissioning of some IRA arms in advance of allowing Sinn Féin into talks.

For the British it would be a gesture of proof that the war was over for sceptical unionists.

But republicans regarded it as an insistence on what amounted to surrender that would split the republican movement.

State papers released on Tuesday show scepticism in the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and the British Army about the military benefits of decommissioning.

They also show scepticism in the heart of the UK government, according to the former US Congressman Bruce Morrison.

In July 1995 he told the Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) John Bruton that Michael Ancram, the minister of state in the Northern Ireland Office (NIO), had "acknowledged that the surrender of weapons was unrealistic and the British knew that" in a meeting with an Irish-American delegation.

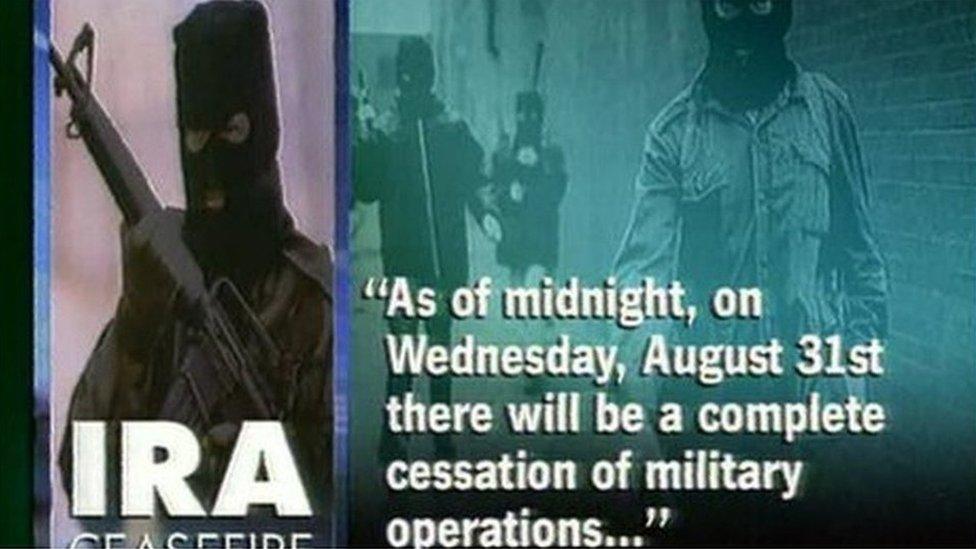

There was a push to make progress on decommissioning ahead of Bill Clinton's (left) visit to Northern Ireland in 1995

It was a view shared by David Watkins, a senior civil servant in the NIO's Central Secretariat.

He is quoted in Irish Department of Foreign Affairs papers in November 1995 as admitting that it was "politically not very astute of the British government to make a precondition of something, Washington Three, which they knew was not deliverable."

The Clinton visit

The days and weeks before the Clinton visit saw a renewed emphasis on the decommissioning issue.

The SDLP leader John Hume reported back to the Department of Foreign Affairs on a private meeting with the prime minister.

He said that Mr Major "stressed that he totally recognised the courage and pressures" on the Sinn Féin leaders Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness but that "he had to sort out decommissioning because of the pressures on him in the Tory party".

At the time the Conservatives were deeply divided over Europe.

Mr Major's position was being constantly undermined by colleagues both inside the cabinet and on the backbenches.

There were intense efforts to make progress on the decommissioning issue in immediately ahead of the Clinton arrival.

In a telephone call with Mr Major, the taoiseach told the prime minister that it was his "considered assessment" that there could be no progress on "Washington Three" before the US president set foot on Irish soil.

To which Mr Major replied: "Then we won't get all-party talks."

Both men were right - at the time.

The IRA bombed Canary Wharf in London in 1996

At the same time Mr Adams was telling the Irish government that it would be "disastrous" if the visit went ahead and "the peace process collapsed shortly afterwards - the US would feel cheated."

He too was right - at the time.

The Irish government took a different approach to decommissioning, believing it should not be a pre-condition to talks but should happen in a twin or parallel process "during the talks process at the latest", according to Mr Bruton.

'Excessively blase attitude'

There were difficult moments between the two governments' officials.

Paddy Teahon, one of Dublin's most senior officials, wrote to his UK counterpart Sir Robin Butler berating him for British press briefings against other senior Irish officials.

He wrote that he believed that the "press briefers engaged in activity in recent times that is entirely destructive in its effect in both personal and political terms".

He urged an end to the hostile activity.

There was also concern in Dublin about the British government's "excessively blase" attitude to the political situation on the ground in Northern Ireland.

The Tánaiste (Irish Deputy Prime Minister) Dick Spring's special adviser wrote to Mr Bruton to say that the British "have effectively portrayed themselves as the war is over and that the Provos have nowhere to go".

He too was right - at the time.

'Sinn Féin-speak'

Another interesting thing that emerges in the released files is Mr Bruton admonishing his officials for "Sinn Féin-speak" when they referred to decommissioning as part of an overall agreement saying that was not Irish government policy.

As early as July 1995, Mr Bruton was reflecting on what Dublin might do if the IRA ceasefire ended.

He wrote: "If a breakdown does occur it would be helpful if the government can simultaneously criticise both Sinn Féin and the UK thereby impliedly holding the middle ground."

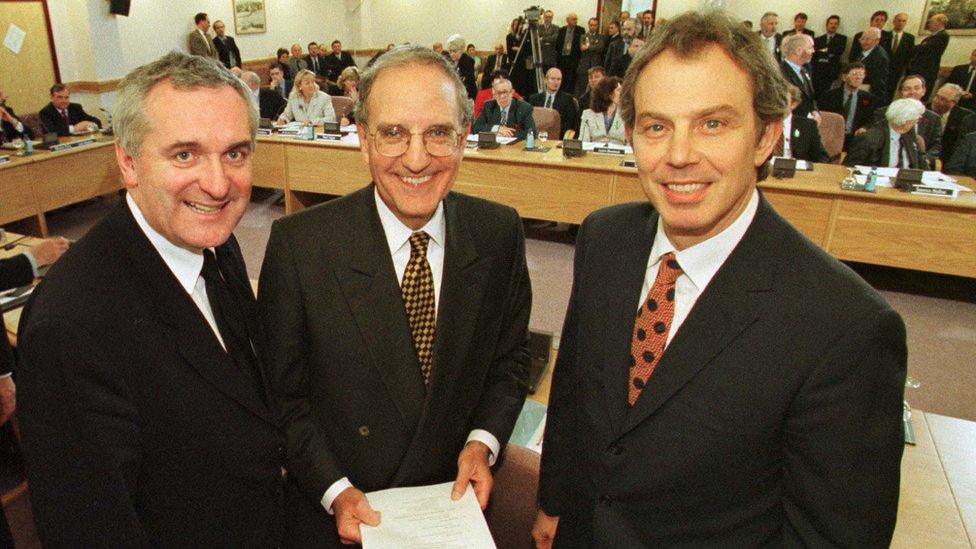

Taoiseach Bertie Ahern (left) and Prime Minister Tony Blair (right) - pictured with Senator George Mitchell - signed the Good Friday Agreement on behalf of the Irish and UK governments respectively

In February 1996, just weeks after the Clinton visit, the IRA resumed its violent campaign with the Canary Wharf bombing in London.

The Northern Ireland peace process had to await the arrival of Tony Blair as UK prime minister and Bertie Ahern as taoiseach before hitting the reset button.

What is noticeable from their conversations is how relaxed they were with each other compared with some of their predecessors.

They spoke about holiday plans and Chinese intelligence bugs in the residences they stayed in while in Beijing.

In July 1997, Mr Blair told the taoiseach that he had said to the unionists that they were "obsessed with the decommissioning issue which in the end is actually symbolic when there is a real issue mainly getting Sinn Féin to accept what everybody else does" - the principle of consent.

That means there cannot be constitutional change to Northern Ireland's position in the UK until a majority there votes for it.

In another call to Mr Ahern, the prime minister said he shared the goal of decommissioning "but we cannot allow any single issue block us from getting down on all the real issues that need to be agreed if we are to get a settlement".

After the second IRA ceasefire, Sinn Féin were allowed into the talks that resulted in the 1998 Good Friday Agreement.

During the week of the negotiations, Mr Blair told the taoiseach that he was going to go to Belfast "to hold [David] Trimble's hand" while the Ulster Unionist leader was presiding over a divided party.

Describing his decision to stay for a number of days in Belfast, the prime minister said: "I've come in for a penny so I may as well be in for a pound."

But despite the successful conclusion of the political negotiations in 1998 it would take until between July and September 2005 for the IRA to decommission.

Related topics

- Published14 July 2021

- Published29 December 2020

- Published27 August 2014