French elections: Divided left fight doomed race of their own

- Published

Jean-Luc Mélenchon is the leading left-wing candidate, but he is well behind the front-runners

Pity the French left-winger as he or she contemplates the upcoming presidential elections.

For the first time in living memory, there is not a single candidate from their camp among the front-runners ahead of the April vote.

The highest-ranking leftist, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, is in fifth place at about 9% in the polls, outperformed by a centrist President Emmanuel Macron, a conservative in Valérie Pécresse and two far-right wingers in Marine Le Pen and Eric Zemmour.

Daggers drawn

As things stand, the chances of a left-wing candidate making it through to the second round - let alone winning the election like François Hollande in 2012 and François Mitterrand years before - look like a pipe dream.

What's more, despite the voters' anguished pleas for unity, the party machines have merely responded with yet more division.

With 11 weeks to go until Round One, the Socialists and the Greens are at daggers drawn over which of their respective candidates, Anne Hidalgo and Yannick Jadot, is the true champion of the mainstream left.

Anne Hidalgo and Yannick Jadot see themselves as the true candidates of the left

From his more radical perspective, and from the advantage of a higher poll score, Jean-Luc Mélenchon looks on both with ill-disguised disdain.

Then there is the Communist, Fabien Roussel, determined to keep his party's identity alive. And he's not doing badly, given that at 3% he is equal with Ms Hidalgo. Add to that anti-capitalists Nathalie Arthaud and Philippe Poutou, fighting their own battle on the fringe.

Seven in race for the left

One left-wing candidate, ex-minister Arnaud Montebourg, has decided to call it a day, arguing that to continue in the race with such a multitude of candidates would be to "add disorder to confusion".

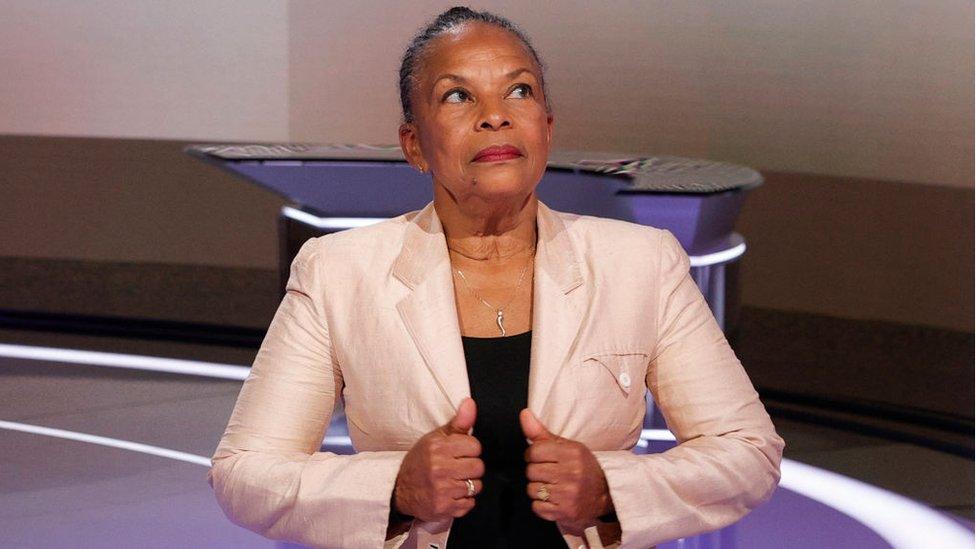

But that was more than offset by the declaration of another former minister, Christiane Taubira. So there are still seven left-wingers in the running.

Christiane Taubira, a former justice minister, hopes that a "popular primary" could give her the edge

Moreover her late entry into the race merely sowed more ill-feeling where there was already plenty to go round.

Hailed by many, especially the young, as an inspirational figure because of her battles against racism and for gay marriage, Ms Taubira was hoping to play a "deus ex machina" kind of role, uniting the discordant tribes behind her.

French elections 2022

The polls currently put Emmanuel Macron in the lead, followed by Valérie Pécresse of the Republicans

April 10 Round One: If one candidate wins 50% of vote they win outright

April 24 Round Two: The two front-runners go into a run-off to decide the presidency

Working in Christiane Taubira's favour has been a grassroots project called the "Popular Primary", in which at the end of next week left-wing supporters who register on a website will get to choose which candidate best expresses their vision and should therefore represent the left in April.

With enough participation in the so-called primary, the argument goes, whoever emerges as the most popular leader on the left will have the moral authority to demand that the others all stand aside, which they will of course do in the interests of the greater good.

It may sound plausible. In reality the project is doomed.

'Too many heads'

Mr Mélenchon and Yannick Jadot have both said they want nothing to do with the business, believing it was conceived by supporters of Christiane Taubira to boost her entry into the race.

Anne Hidalgo feels the same, but her position is complicated because some in her Socialist Party may actually be rooting for Ms Taubira because they think Ms Hidalgo has made such a lousy campaign of it so far.

Add to the picture that in this popular primary there are also three other potential candidates - the totally unknown Anna Agueb-Porterie, Charlotte Marchandise and Pierre Larroutourou - and you can see why the average left-wing voter might be tempted to start tugging the rug.

"There are simply too many heads on too small a stage," as Libération newspaper, house journal of the French left, put it this week. "True, no-one really believed in a grand union of the left. But who would have thought the fingers on one hand would be insufficient to count the candidates?"

Of course in the French system having a multiplicity of candidates on the left or right is not necessarily a handicap.

It has been 10 years since a left-winger won the presidency in François Hollande

That's as long as there is a clear front-runner who, having qualified for the run-off, can count on the first-round votes of their erstwhile rivals, who would now be ministerial hopefuls.

What went wrong for French left

When Mitterrand won the presidency in 1981, he was up against five left-wing and environmentalist candidates in Round One. However, his first-round vote was 25% and his nearest rival was the Communist, Georges Marchais, on 9%, the same as the highest-ranking leftist Jean-Luc Mélenchon is polling today.

In late-night sessions in Paris salons the arguments roll on about why things have come to this pass:

Is it because the French left is too doctrinaire, too wedded to theory and not sufficiently pragmatic like the German Social Democrats, who are now in power?

Is it because of a fault-line dividing old-style one-nation Socialists from the new identity politics brigade?

Is it because the dream of the left was shattered by the mediocrity of François Hollande? Is it because the Fifth Republic system needs big beasts to be in charge, and the left congenitally cannot produce them?

Is it because, paradoxically, France is already a left-wing country, economically speaking, so people who vote far right actually want to keep all the good things that Socialism has achieved? Is it that the left is scared of talking about immigration and crime?

Or is it simply that Emmanuel Macron craftily mastered this all along, splitting the left apart in 2017? The one thing it has not spent the last five years doing is getting back together.

You may also be interested in this:

Why France is declaring Josephine Baker a national hero