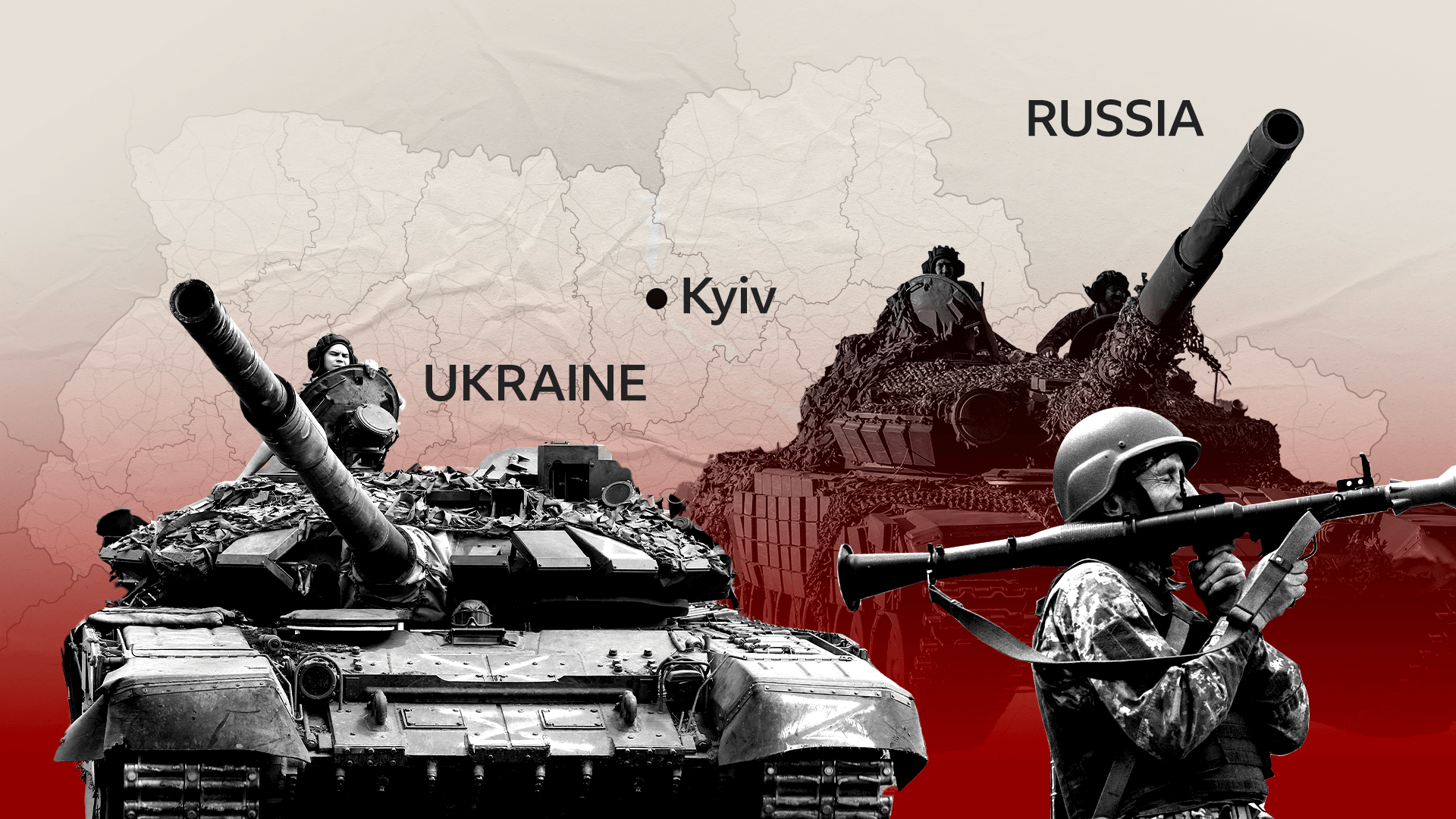

Putin threats: How many nuclear weapons does Russia have?

- Published

US President Joe Biden has warned that the risk of a nuclear "Armageddon" is at its highest level for 60 years.

Mr Biden said that Russian President Vladimir Putin was "not joking" when he warned that Moscow would use "all means we have" to defend Russian territory. Mr Putin has also said that the US created a "precedent" by using nuclear weapons in World War Two.

But analysts suggest Mr Putin's words should probably be interpreted as a warning to other countries not to escalate their involvement in Ukraine, rather than signalling any desire to use nuclear weapons.

Nuclear weapons have existed for almost 80 years and many countries see them as a deterrent that continues to guarantee their national security.

How many nuclear weapons does Russia have?

All figures for nuclear weapons are estimates but, according to the Federation of American Scientists, Russia has 5,977 nuclear warheads - the devices that trigger a nuclear explosion - though this includes about 1,500 that are retired and set to to be dismantled.

Of the remaining 4,500 or so, most are considered strategic nuclear weapons - ballistic missiles, or rockets, which can be targeted over long distances. These are the weapons usually associated with nuclear war.

The rest are smaller, less destructive nuclear weapons for short-range use on battlefields or at sea.

But this does not mean Russia has thousands of long-range nuclear weapons ready to go.

Experts estimate around 1,500 Russian warheads are currently "deployed", meaning sited at missile and bomber bases or on submarines at sea.

How does this compare with other countries?

Nine countries have nuclear weapons: China, France, India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, the US and the UK.

China, France, Russia, the US and the UK are also among 191 states signed up to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT).

Under the agreement, they have to reduce their stockpile of nuclear warheads and, in theory, are committed to their complete elimination.

And it has reduced the number of warheads stored in those countries since the 1970 and 80s.

India, Israel and Pakistan never joined the NPT - and North Korea left in 2003.

Israel is the only country of the nine never to have formally acknowledged its nuclear programme - but it is widely accepted to have nuclear warheads.

Ukraine has no nuclear weapons and, despite accusations by President Putin, there is no evidence it has attempted to acquire them.

War in Ukraine: More coverage

ANALYSIS: Putin's dream of victory slipping away

ON THE GROUND: Ukraine war in maps

READ MORE: Full coverage of the crisis, external

How destructive are nuclear weapons?

Nuclear weapons are designed to cause maximum devastation.

The extent of the destruction depends on a range of factors, including:

the size of the warhead

how high above the ground it detonates

the local environment

But even the smallest warhead could cause huge loss of life and lasting consequences.

The bomb that killed up to 146,000 people in Hiroshima, Japan, during World War Two, was 15 kilotons.

And nuclear warheads today can be more than 1,000 kilotons.

Little is expected to survive in the immediate impact zone of a nuclear explosion.

After a blinding flash, there is a huge fireball and blast wave that can destroy buildings and structures for several kilometres.

What does 'nuclear deterrent' mean and has it worked?

The argument for maintaining large numbers of nuclear weapons has been having the capacity to completely destroy your enemy would prevent them from attacking you.

The most famous term for this became mutually assured destruction (Mad).

Though there have been many nuclear tests and a constant increase in their technical complexity and destructive power, nuclear weapons have not been used in an armed confrontation since 1945.

Russian policy also acknowledges nuclear weapons solely as a deterrent and lists four cases for their use:

the launch of ballistic missiles attacking the territory of the Russian Federation or its allies

the use of nuclear weapons or other types of weapons of mass destruction against the Russian Federation or its allies

an attack on critical governmental or military sites of the Russian Federation that threatens its nuclear capability

aggression against the Russian Federation with the use of conventional weapons when the very existence of the state is in jeopardy

The use of nuclear weapons is far from likely

The shadow of nuclear weapons has hung over this conflict from its earliest days - and that has been a deliberate choice on the part of Vladimir Putin.

He has raised their use at moments when he has been on the back foot - for instance after the failure of his initial February plan to quickly overthrow the Ukrainian government and now again when a Ukrainian offensive has driven his forces back,

His hope will be that a reminder of the devastating power of these weapons will intimidate and deter his opponents and force them to rethink how far they are willing to push.

There is also a domestic motive - the Russian population will be worried by the partial mobilisation and Putin's own claims that Nato is somehow threatening Russia itself. Talking about nuclear weapons is a way of reassuring domestic opinion that despite this dark turn, the country remains capable of defending itself.

Russian military doctrine says nuclear weapons will only be used if the Russian state itself is threatened. It was notable that Putin framed their use in a defensive sense responding to what he claimed were Western nuclear threats.

His reference to this not being a 'bluff' referred to a situation when Russia's territorial integrity was threatened. An important question is how far Russia sees its territory extending after the upcoming referenda in Ukrainian territory.

All of this suggests that the use of nuclear weapons is far from imminent or even likely.

While the possibility of their use can not be dismissed, especially if Putin feels the security of the state threatened, the response from the West for the moment will likely be to watch closely Russia's actual behaviour rather than the rhetoric and to remain focused on their strategy.

Related topics

- Published20 September 2022

- Published24 February 2023

- Published28 February 2022