Ukraine: How a week of war has transformed lives

- Published

Living in the basement - Rustam, Liana, Vera, and Tyson the cat

Seven days which sparked a burning patriotic resolve in Ukraine, which propelled people the world over, from presidents and prime ministers, bankers and business leaders, football stars to figure skaters, artists and activists, to stand up and be counted to condemn Russia's aggression.

The Russian rouble collapsed, the UN General Assembly called on Moscow to pull out; Russian leaders denounced this "Russiaphobic frenzy". And, on the ground, swathes of Europe's second-largest country were reduced to smoking ruins, a harrowing echo of Russia's blistering campaigns in Grozny and Aleppo.

In the days before Russia invaded Ukraine, Kyiv was a European city of golden-domed cathedrals gleaming in the night, brightly-lit restaurants serving steaming bowls of borsch, corner kiosks pouring coffee behind frosty winter windows.

And the world was a place where many thought a blitzkrieg across a border was only history's business. At the Munich Security Conference, many a government minister quietly told me "I just don't think it will happen". And, of course, not against the capital.

But in her home in Kyiv, 37-year-old Liana was ready with bags packed, including some books; clothes ironed, enough money from an ATM to last a while. Her mother Vera refused to do the same. Her friends poked fun at her. But Liana's son Rustam, a bespectacled 13-year-old wired to his smartphone, was ready too.

In the dead of night on Thursday 24 February, in a city which couldn't sleep, rumours and reports electrified social media and exploded in chat groups.

This snippet "Russian action will begin at 4am" shot through cyberspace with the kind of chilling precision Western intelligence reports had used for weeks to warn of "an imminent invasion" by nearly 200,000 Russian troops and heavy weaponry now massed along the borders.

Local flights kept cancelling, parents wondered if they should take their children to school in the morning, journalists started asking each other if they were staying.

By 05:00, posts cascaded across the internet - "hearing thuds" in Kyiv, Kramatorsk, Melitopol, Chernobyl, Odessa. The list was long.

At 05:58, Ukraine's Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba tweeted "Putin has launched a full-scale invasion". Hours earlier, President Vladimir Putin had announced the start of a "special military operation" in eastern Ukraine.

At 06:00 Liana called her mother. "I told you so. Are you packed?"

By nightfall, roads out of Kyiv were gridlocked. Homes were emptied of energy as a city went underground, to basements and bomb shelters, to subway stations with marble stairways and magnificent mosaics built deep below in the 1960s to also double as Cold War bunkers.

It was a day which ended the tidy life of Liana, who runs a small office supply company, and terrified her mammoth Maine Coon cat, who found he couldn't live up to his namesake - the US professional boxer Mike Tyson known as Iron Mike.

I met them all in a cavernous basement in the city centre, two floors below ground, where our BBC team also took shelter. A tight-knit family, including mother Vera with a shock of red hair and an even warmer smile, took up residence on thin mats on the hard floor next to ours.

Lyse broadcasting from the basement

"It was a difficult night," declared champion boxer-turned-mayor Vitali Klitschko as the day dawned on Saturday with news that Russian forces were now advancing on Ukrainian cities from the north, east, and south. "Russian troops are not in our city," he reassured "Kyivians" who woke - if they slept at all - asking that very question.

His rallying cry was amplified hours later, on that day, and every day after, by the comedian-turned-president-in-a-suit-turned-wartime-leader-in-olive-green-attire. "We won't lay down our arms,' President Volodmyr Zelensky declared, rebuffing "fake news" that he'd done the opposite.

"Are you worried?" I asked Liana. "I can't be sad, I must be hopeful to support our president," she exclaimed in her own act of resistance underground. Tyson, however, was hiding upstairs, under a bed. And Liana worried about her father living north of the capital, in a village close to Chernobyl, now occupied by Russian forces. He'd crept out of his home last night, crawling through fields under cover of darkness, to see Russian troops throwing tarpaulin over heavy weaponry to hide them from view.

In Kyiv, air raid sirens were now blaring day and night, a chilling soundtrack of the city. A weekend curfew came in force. We discreetly rigged up a smartphone to broadcast from the basement where at least five dogs, including Kurt a puffy white Pomeranian named after the American singer-songwriter, and Andrew, a trembling Yorkshire terrier, never seemed to bark.

On Sunday, Liana and Vera rushed pell-mell toward me. "What happened?" I asked, trying to suppress a note of worry. "Thank you, thank you!" they shouted excitedly, words tumbling over the other. Their friends in the US, Britain, and the UAE had sent them screenshots of our BBC broadcast.

There they were, in the corner of the screen, quietly sitting along the wall. "Now they know we're safe!" they gushed, reflecting that surge of anxiety worldwide in the large Ukrainian diaspora as the invasion intensified.

But news from Liana's father was ominous. He could hear Russian tanks rumbling past, heading south towards Kyiv. His electricity was now cut; he cooked potato soup outside, on an open fire in sub-zero temperatures, all the while trying to hide the flame.

By Monday, when the weekend curfew lifted, satellite images shared by Maxar technology revealed a massive Russian armoured column, stretching along 40 miles (64km) of road, stopped just 20 miles from Kyiv. The plight of other cities was even more foreboding. Residential areas of Kharkiv, the second largest city to the west, were being pounded - so was Chernihiv to the north.

Sleeping quarters

Thin mats have been replaced by mattresses in this new subterranean world - Ukraine beds down and digs in. All through the night, smartphones glow under covers. Liana, like everyone else, connects incessantly with friends and family across Ukraine and beyond.

A Russian missile has slammed into her father's vegetable garden, smashing his sustenance for the long run. Rustam, intense at the best of times, is now an extension of his phone saturated by everything Ukraine. Sometimes Tyson the cat emerges from under his bed above ground for a comforting cuddle.

Russia's Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu has vowed to continue the offensive until "its goals are achieved".

It's been a week of war. Unparalleled sanctions imposed on Russia are being described as economic war. A war crimes investigation has already been launched, and everyone everywhere is taking a stand. Even the International Feline Federation (FIFe) has banned the import of any Russian breeds of cats.

The southern city of Kherson has fallen. Mariupol is encircled by Russian forces, without electricity, running water, or enough food. The armoured convoy north of Kyiv still hasn't made its move.

And Liana is in a flood of tears. "Eight Russian soldiers barged into my father's house last night looking for cigarettes, and they've taken over his house," she wails. She hears a story about a family who tried to flee and was shot dead on the spot. They're looking for young men able to fight. She says her elderly father sits in a chair and doesn't dare move.

In some areas, whole neighbourhoods have been obliterated by Russian firepower or seem to be under its sway.

Now it's the second week. More than a million Ukrainians have fled. Many are staying to pick up guns to fight. "We are the nation that broke the plans of the enemy in the first week," boasts President Zelensky in his latest video message, still dressed in olive-green.

President Putin announces his "special military operation is going according to plan", vowing to "destroy this anti-Russia created by the West".

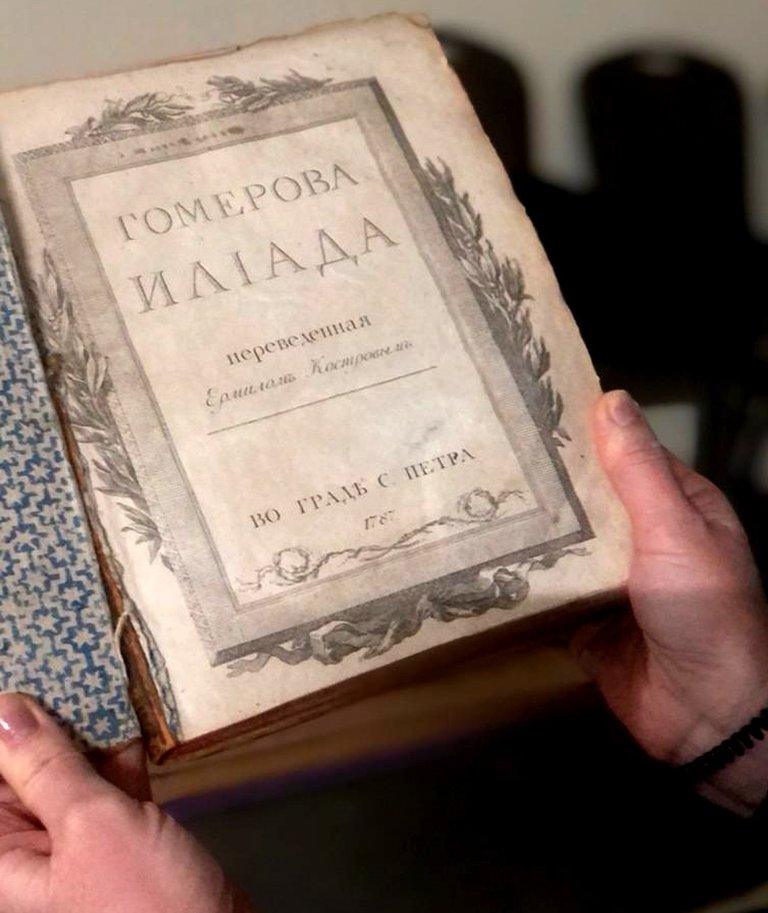

Last night Kyiv was rocked by explosions, coming ever closer to city centre, which painted the sky orange. When the night curfew lifts, Liana and her mother Vera make a dash to the shops to check for supplies - including cat food - on fast-emptying shelves. Then she settles in to try to read the tome she packed for what could be a long and anxious haul. It's a Russian-language version of Homer's the Iliad, a rare book given two centuries ago to Russia's Catherine the Great, the empress known for bringing Russia into Europe's cultural and political life.

Russian-language version of Homer's the Iliad

Russia attacks Ukraine: More coverage

THE BASICS: Why is Putin invading Ukraine?

INNER CIRCLE: Who's in Putin's entourage, running the war?

IN DEPTH: Full coverage of the conflict