Ukraine war: Kyiv prepares for Russian attack

- Published

When the Russian offensive started, as sirens sounded in Kyiv for the first time, some people here feared that the city might fall by the afternoon.

Reports were coming in of a long convoy of armour and heavy weapons pushing down from the north-west. Military analysts had a high opinion of the Russian army. It had, they said, been professionalised, with invaluable experience of perfecting weapons and seasoning men in the war in Syria. The tactical errors I had seen the Russians commit when they tried to crush a rebellion in the republic of Chechnya in 1995 were, I was told, ancient history.

The consensus about the Ukrainian armed forces on the first day of the war was that they were much stronger than they had been in 2014, when they could not stop Russia seizing Crimea and establishing two breakaway enclaves in eastern Ukraine. But Russia had the numbers and the firepower. The Ukrainians, it was said, would rediscover the truth of an aphorism attributed to Stalin: "quantity has a quality of its own."

The first two weeks of the war proved that those predictions were wrong. The Russians blundered; the Ukrainians resisted. Around Kyiv the Russian advance stalled. In the south, it was a different story. They worked steadily towards opening a land corridor between Crimea and Moscow's enclaves in eastern Ukraine.

But it has been clear from the outset that control of Kyiv is crucial to winning arguments in politics as well as on the battlefield. While President Volodymyr Zelensky's government holds the city, he can claim not to be defeated, and President Vladimir Putin in the Kremlin cannot claim victory.

The last couple of days have been bright and sunny, after more than a week of thick cloud. That means satellites have a clear view of movements on the ground. One conclusion is that the 40-mile Russian convoy north-west of Kyiv is slowly dispersing and reorganising. The latest word from the US Department of Defense is that the rear elements are catching up, but the vehicles closest to Kyiv are not moving.

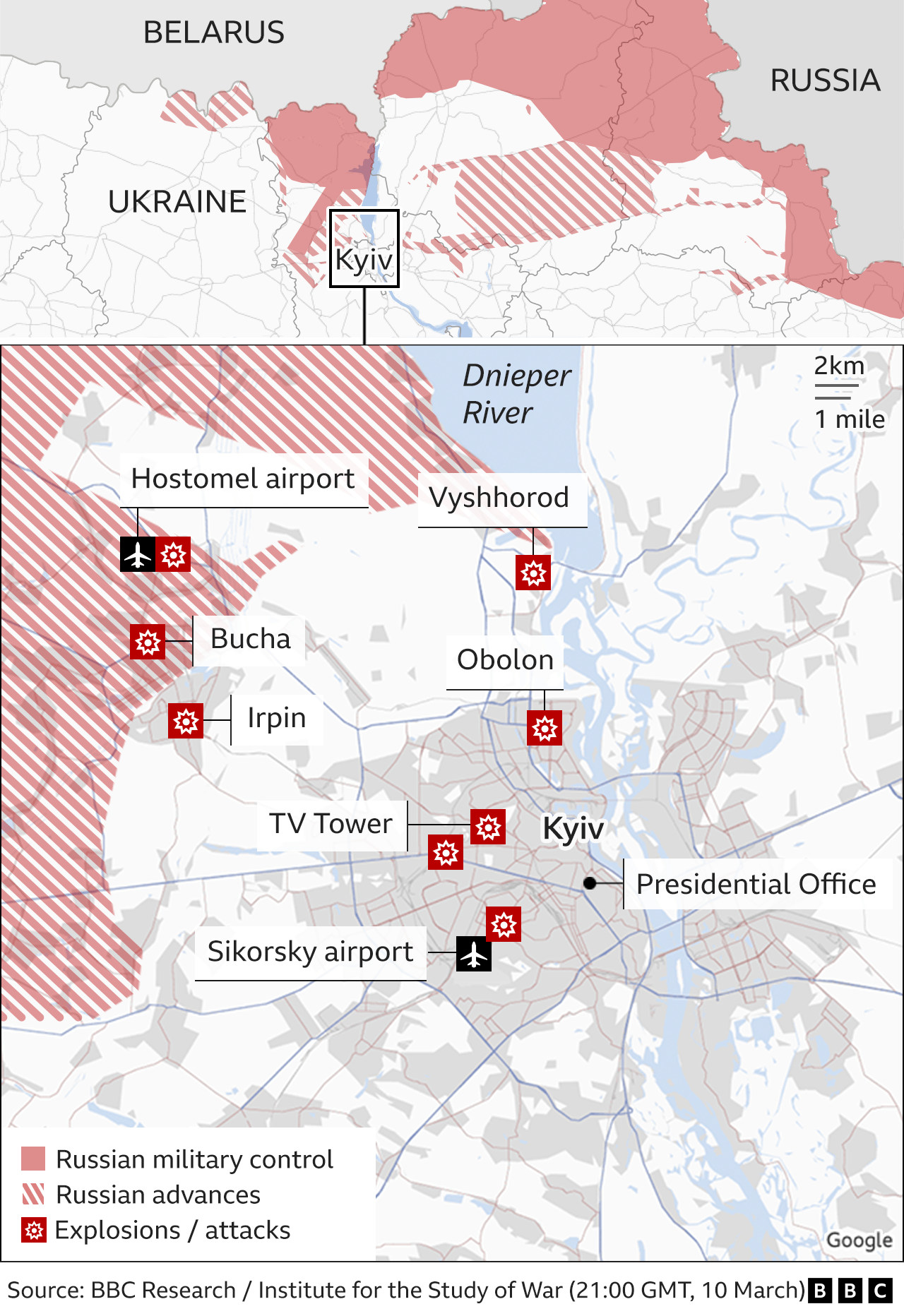

The fighting around Kyiv has been concentrated in the north-west and has been going on since the first morning, when Russian airborne troops landed at a cargo airport near Hostomel and Irpin, small commuter towns that evacuees say are now badly damaged. They looked to be trying to secure a staging area for a push into Kyiv. But Ukrainian troops stopped them.

In the last few days, I have seen more defenders moving forward to continue the fight around Irpin and the Hostomel airport and heard steady artillery fire from the Ukrainian side from gunlines concealed in belts of thick woodland.

The heavily contested north-west is just a 20-minute drive from the centre of Kyiv, which has barely been touched, although sirens sound regular alerts.

In the week or so that I have been here the Ukrainians have improved their physical defences, which in places barely existed. Checkpoints that were just a few concrete blocks have become barricades. Across the city men have been filling and positioning sandbags. Kyiv's metalworkers have been busy. At strategic junctions, and on the dual carriageways that run out of Kyiv steel anti-tank obstacles stand ready.

Kyiv is a grand city of broad, sweeping avenues, bisected by narrower streets often paved with lumpy cobblestones. Many of the buildings have extensive basements and cellars. Street fighting here, if it happened, could grind on for months.

The city sprawls along both banks of the Dnieper, one of Europe's great rivers. Docks and marinas leading off the river are still frozen. Crossing the water under fire would be a formidable military undertaking. The bank on the west side of the river, near the government buildings and the great cathedrals, is steep and heavily wooded. Defenders would have many advantages.

But crossing the Dnieper might not be on Russia's agenda until it is able to control both banks. One theory is that the stalled offensive from the west and north-west is not just because of Ukrainian resistance and what appears to be the Russian army's own badly handled logistics. A column coming from the east has been moving slowly, and the generals might be waiting for it to catch up.

The Russians attempted to move a regiment of tanks into Kyiv's eastern approaches on Thursday. They were mauled badly as they rumbled slowly down a highway in broad daylight. Drone pictures showed that the tanks were bunched together making easy targets for Ukrainian artillery or drones. It was another tactical blunder for Moscow.

It is not clear whether Russia plans to encircle Kyiv or attempt to force a surrender by thrusting into the centre with armour supported by infantry. The choices are not great for them. Direct attacks have so far been stopped. Encircling a big city might take too many men.

One possibility is that President Putin expected the rapid collapse of a government that he has dismissed with contempt as a Nazi collaboration with the west and did not think his soldiers would need to do either.

It is certain that Putin and his generals are reassessing, regrouping and will not accept defeat. Putin's mission has been to restore Russia to what he believes is its rightful place as a world power. In a country the size of Ukraine - only Russia itself is bigger in Europe - victory in Kyiv is the most direct way for him to declare mission accomplished.

Without a doubt the Russian armed forces have been operating at half power and half speed. That is partly due to their own mistakes, and partly because the Ukrainians are proving to be formidable, nimble opponents. The stalled attacks around Kyiv have turned into a respite for the city's defenders, allowing them time to dig to improve defences that were rudimentary, and presumably to receive some of the increasingly sophisticated weapons that NATO is bringing into Ukraine.

A question that nags uncomfortably at the minds of many in Kyiv is whether President Putin will conclude that the time has come to turn the deadliest conventional weapons in Russia's arsenal against the city's defenders. So far that has not happened. If it does, many more people will die and terrible damage will be done.

Some people here do not believe President Putin will hammer Kyiv in the way that cities in eastern and southern Ukraine have been attacked. They argue Putin will hesitate to destroy an ancient city which has been at the centre of Russian culture, religion and history. Some of the same people also believed Russia would not invade.

Others fear that if Russian infantry and armour are held up, Putin and his generals will default to the tactics they are using in Mariupol in the south, surrounding the city and attempting to break the will of its defenders with artillery and air strikes. It is a method that worked well for the Russians in Syria, and in the 1990s when Grozny, the capital of the breakaway Russian republic of Chechnya, was flattened.

The next few weeks will be critical for the future of Kyiv, and for the wider war over the future of Ukraine. If Russia cannot reactivate its attack on the capital, its defenders will grow in confidence and the strength and the morale of Russian forces, including conscripts, will take more blows.

If the Putin regime can find a way to end resistance here, the president will be closer to achieving his war aim of ending Ukraine's independence. Forcing the country back into Russia's orbit, in the face of what would most likely be a Nato-backed insurgency, would be an altogether more difficult job.

War in Ukraine: More coverage

WAR CRIMES: Could Putin be prosecuted?

IN DEPTH: Full coverage of the conflict

Related topics

- Published11 March 2022