A bomb hit this theatre hiding hundreds - here's how one woman survived

- Published

Mariia, who was volunteering at the Ukrainian Red Cross, tried to help those injured in the attack but her kit was inside the theatre

As the port city of Mariupol was being razed to rubble by Russian bombs, hundreds of civilians, mostly women and children, went to hide in a theatre near the waterfront, a grand Soviet-era building. Last Wednesday, a bomb hit and - within seconds - the building had been split in two and left in ruins. We still do not know how many died, but the BBC has spoken to survivors who described for the first time what happened when the bomb fell.

All morning, Russian planes had been circling the skies above the city.

Mariia Rodionova, a 27-year-old teacher, had been living in the theatre for 10 days, having fled her ninth-floor apartment with her two dogs. They camped next to the stage in an auditorium near the back of the building.

That morning she had got some fish scraps from an outdoor field kitchen to feed her dogs, but then realised they had not drunk any water. So at about 10:00, she tied her dogs to her luggage and made her way towards the main entrance where a queue was forming for hot water.

And then the bomb fell.

There was the sound of a clap, thunderous and loud. Then the sound of broken glass. A man came from behind and pushed her to a wall, protecting her with his own body. The blast was so loud that she felt intense pain in one of her ears, so intense she thought her eardrum must have split. She only realised it had not because she could hear the screams of people. The screams were everywhere.

The force of the blast threw another man against a window. He fell on the ground, his face covered with broken glass. A woman, who also had a wound on her head, tried to help him. Mariia, who had been volunteering at the Ukrainian Red Cross in Mariupol, gathered her senses enough to shout over, telling her to stop.

Five-year-old screaming

"I said 'Wait, don't touch him. I'll bring my first aid kit and I'll help you both'," she recalled. But her kit was inside the theatre, and that part of the building had collapsed.

"There was only rubble," she said. It was impossible for her to get in.

"For two hours, I couldn't do anything," she said. "I just stayed there. I was in shock."

Vladyslav, a 27-year-old locksmith who does not want to use his full name, had also wandered into the building that morning. He had some friends there and went to look for them. He was near the main entrance when the explosion hit. He ran with others into a basement and, 10 minutes later, heard the building was on fire and emerged to a scene of chaos.

"Terrible things were happening," he said.

He saw plenty of people bleeding. Some had open fracture wounds. "One mother was trying to find her kids under the rubble. A five-year-old kid was screaming: 'I don't want to die'. It was heartbreaking."

It is likely to have been just one bomb that fell on the theatre that morning, bringing all that destruction with it, analysis by McKenzie Intelligence Services for the BBC has concluded.

"Due to the missile appearing to accurately hit the centre of the building, we believe it is a laser-guided bomb, likely the KAB-500L or similar variant, launched from an aircraft," the London-based group said.

"The nature of the explosion indicates it was armed with an instantaneous fuse, so was unable to penetrate the ground floors."

From the accuracy of the strike it is very likely that the theatre was the chosen target.

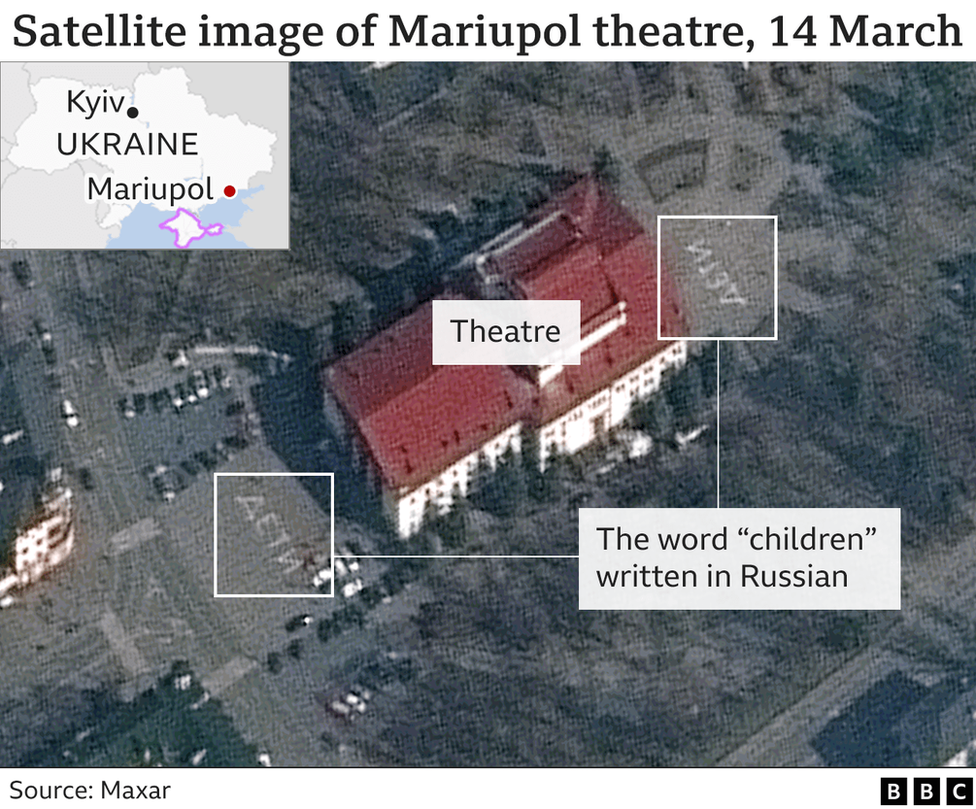

Satellite imagery released by the US company Maxar, from the days before the attack, show the word "children" in Russian was clearly painted on the lawn in front of the theatre, visible to any passing bomber.

Russia denies attacking the theatre. It has also denied hitting civilian sites in Ukraine, although its attacks on countless residential buildings and other non-military facilities have been well documented across the country and nowhere more brutally than in Mariupol.

Andrei Marusov, an investigative journalist from Mariupol, had visited the theatre two days before the attack. "Everybody knew that it was a focal point for many women and children," Marusov, who is a former chairman of the advocacy group Transparency International Ukraine, said. "There were only civilians there."

That Wednesday, the day of the bombing, he had gone up to the top of his building at 06:00 to survey the city. The planes were still buzzing through the air. He said Russian planes had been shelling and bombarding the area where the theatre was, that Sea of Azov waterfront all morning.

"I saw that the city centre was covered by fire and constant explosions," he said.

Mariia also remembers military planes "making circles" near the theatre that morning, and "throwing bombs somewhere else". But it was not unusual for her to spot military planes flying in the area. She had got used to their sound.

There are still many details that remain unclear about the attack. It is thought that up to 1,000 people were sheltering in the drama theatre. Some appeared to have based themselves in its underground bunker or bomb shelter, according to others who hid in the building and city authorities. Mariia saw others living in crowded corridors on overground floors.

One thing which is clear from the accounts of the people the BBC spoke to, is that people would wander around the complex, its corridors and grounds, and others would come and go.

The destroyed theatre that Mariia walked away from

The day after the attack, the city council said 130 people had been rescued. A further update said it was possible that many had survived. But there has been no news since then. The city is in such a desperate state that there may never be a clear picture of how many were there and how many survived.

Mariia's home inside the theatre for the days she was there was in an auditorium hall with a chandelier, and she nestled right next to the stage because her dogs had drawn some complaints. She said there were about 30 people in that hall and it is her belief that they must have all perished when the bomb hit. It was sheer luck that she had stepped outside at that moment.

After the blasts she was unable to find her dogs and it was a moment of desperation: "For me," she said, "my dogs were more important than anything."

Vladyslav said he saw many people coming out of the building, something that Mariia saw as well.

Escaping the city

"Some were with their luggage," she said. "No-one knew what to do, and the area was still being shelled."

Standing outside the theatre, she too looked at the damage. She realised it made no sense to look for another shelter. It had been a few stunned hours and she eventually left.

She tried to stop any car leaving the city. "People were in panic," she said, "no-one took me in their car." She started to walk along the coast.

"I needed to get out of the city."

First, she got to the village of Pishchanka. "I met a woman," she said, "who asked if I was OK. I started to cry." She was offered tea and food, and invited to spend the night. The next morning, she kept walking, until she reached Melekyne. A curfew meant she had to stop at 20:00. A day later, she walked to Yalta. The following one, to Berdyansk. "I walked all that time," she said.

Mariupol has seen the worst horrors of Russia's aggression on Ukraine. The invading troops have surrounded the city and attacked it relentlessly for almost a month, from the air, land and, in recent days, also from the sea. About 100,000 people remain trapped, subjected to a medieval-like siege. No electricity, no gas, no running water.

When Mariia left her flat for the theatre, her grandmother, who lived with her, refused to go. "She just said: 'It's my apartment, my home. I'm going to die here'."

Mariia is still waiting to hear whether she is alive.