French election: A battle of bad reputations for Le Pen and Macron

- Published

Both sides are under fire from their critics

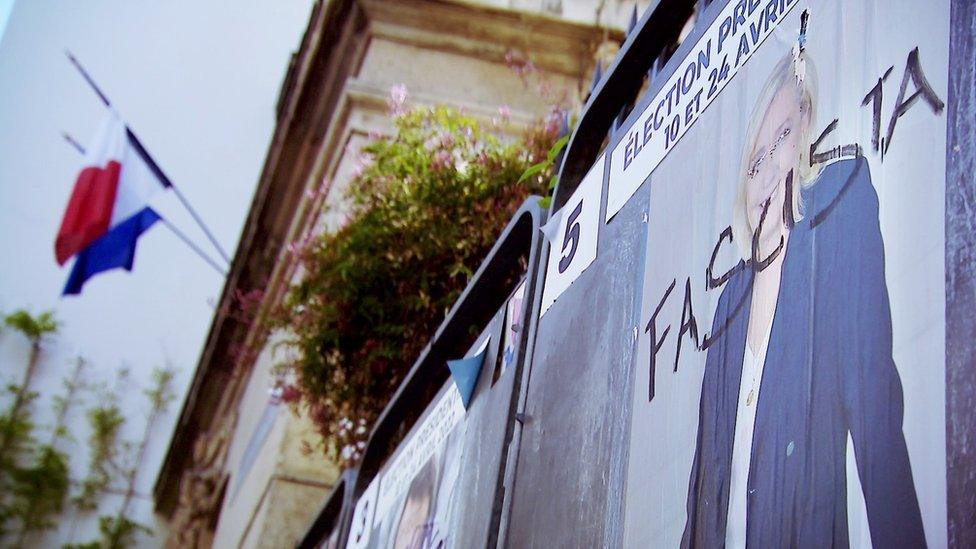

Finding a French election poster for either top candidate that hasn't yet been defaced is almost like a treasure hunt.

Ahead of this Sunday's decisive presidential election, colourful slurs are scrawled everywhere: "fascist" or "dirty liberal"; "racist" v "elitist" on billboards for Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron.

It doesn't take long to work out what's aimed at whom. The violent dislike many voters express for one or both sides in this election can take your breath away.

Marine Le Pen is used to it.

The daughter of an infamous anti-immigration, nationalist politician who repeatedly spoke of Nazi gas chambers and the Holocaust as "a detail of the history of the Second World War", she has spent years trying to escape Jean-Marie Le Pen's toxic shadow.

This is her third attempt at the presidency, and she is the softest public version of herself yet. From her pastel make-up, to a notably warmer speaking tone and her focus on the working French struggling to make ends meet, rather than concentrating on the classic far right priorities: law and order and immigration.

"Marine", as she now likes to be known, has tried oh so very hard to rebrand herself as a patriotic centrist.

I put it to her that her critics call her "un-electable'; describing her as too far right and radical.

"I'm not radical, sorry!" she retorted. "The current government has been lead by the privileged minority for the privileged minority. That's the reality."

"I am running for president to change that. To establish a government of the people, for the people... giving back power to the people."

Watch: What far-right leader Marine Le Pen said before…and now

In fairness, she's persuaded many, with popularity ratings she never enjoyed previously. But large swathes of France simply don't buy it.

Nagette, a young Muslim office worker, told me Le Pen could '"change her mask as often as she liked" but that she remained far-right in her roots and policies.

She'd be voting Emmanuel Macron, she said, to keep Le Pen out.

When I followed Le Pen on her campaign trail in the south of France a few days ago, her press officers had us journalists meet them in a car park at an arranged time. We then were left to hang around irritably, until they suddenly announced the name of the village Marine Le Pen would imminently appear in for a campaign event.

It was quite surreal.

But there is a logic to it. If the press didn't know ahead of time where Marine would be glad-handing, then her shouting, chanting, at times aggressive detractors wouldn't be there either, to ruin her PR event.

Emmanuel Macron had a far easier time in 2017. His first presidential campaign.

Then, he was a fresher-faced, brazen political disrupter, claiming to be neither of the left nor the right, just promising a bright future for all French men and women.

Middle-class French women swooned over him. French businessmen had high hopes for the rabbits they hoped the former boy wonder economy minister might pull out of French tricolour-coloured hats.

Now, he's been tarnished by five years in office, which included presiding over a global pandemic, a war in Ukraine which threatens wider European stability and a big, fat Covid and Russia-tensions linked economic downturn.

Madame Le Pen is not the only one with a reputation problem.

Macron is disparagingly referred to as "Jupiter" or "president of the rich" by his detractors. Many voters say they wouldn't touch him with a barge pole. Which makes Sunday's vote all the more fascinating.

The French often talk about putting a clothes peg on their nose when casting a ballot in the final round of presidential election.

It's about choosing "the best of the worst", people tell you. Preventing the most odious candidate from taking office.

Whether it was to defeat Marine Le Pen or her father before her, French political parties would club together to form a so-called cordon sanitaire to keep the far right out of government.

This election year it's far less clear cut.

The big question is whether voters of the far left will abstain, because of their deep dislike of Emmanuel Macron, even if that might mean ushering Marine Le Pen into the Élysée Palace through the back door.

Voter disdain and voter apathy are arguably the bigger threat for Macron on Sunday than Le Pen herself.

Quite a contrast to the passion you find in international circles when discussing the possibility of a President Le Pen.

French Economy Minister Bruno Le Maire, told me he thought the wider world, not only Europe, was aware of what was at stake in this election: two visions of the future of France and two visions of the future of Europe, he said.

Especially in light of the raging Russia-Ukraine crisis.

Brussels and Washington are watching the vote extremely closely, crossing their metaphorical fingers. Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelensky and well-known Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny have both called for Macron to be re-elected.

France has the EU's only significant military force. It's the bloc's second largest economy and it's been playing an increasingly dominant European role since the departure from politics of EU grande dame Angela Merkel, which left Berlin somewhat weakened on the world stage.

Macron wants to boost EU, Nato and transatlantic relations.

While Le Pen is a euro- and US-sceptic with historically close ties to Moscow and an arms-length attitude towards Nato.

Bruno Le Maire says the world is watching France's election carefully.

"Do you really think when you have war in Europe," spluttered Bruno Le Maire, "that it's good idea for France, for the G7 countries, for all the allies of the French nation to have France, one of the most important political power in Europe, withdraw from the NATO's military command?" he asked.

Because that is what Madame Le Pen proposes.

Mr Le Maire also warned the Le Pen economic programme would be disastrous, he said. Not only for France but the whole of Europe. Also damaging close economic partner the UK, he said.

Marine Le Pen fiercely defends her financial proposals, which include abolishing income tax for the under-30s and helping the hard-up with France's cost of living crisis.

She also claims not to be a danger to the EU.

As part of her attempt to attract more mainstream voters, Le Pen has backed away from her once oft-repeated desire to remove France from the euro currency and from "the tyranny of Brussels".

But her declared intention to unilaterally reduce France's contributions to the EU budget, to restrict the freedom of movement of workers across Schengen passport-free European borders and to declare the supremacy of French law over EU law, in direct contradiction to EU treaties, could end up paralysing the EU from within.

French MEP Nathalie Loiseau, formerly Macron's Europe minister, told me she had gone into politics to help prevent the far right from getting to power.

No-one should downplay the possibility of a Le Pen presidency, she insisted.

Remember Donald Trump's surprise election victory and the Brexit vote, she added - when people went to bed, believing the UK would remain in the EU, only to wake up to a very different reality?

Still, if Marine Le Pen were to beat the odds and become president this Sunday, Nathalie Loiseau said it was very unlikely she'd manage to cobble together a coalition of like-minded countries aiming to dismantle the EU from the inside.

Her closest EU ally, Viktor Orban, wants the EU to keep existing, she explained, so his country can continue to benefit from subsidies. While Poland's Brussels-sceptic coalition was deeply troubled by Le Pen's cosy relationship with Russia.

The campaign slogans of Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron both claim they represent all French people. Considering their very different political programmes and reputations, that is an impossibility.

France is a divided nation.

Race for French Presidency

SCHOFIELD: Le Pen impresses but Macron holds firm in TV debate

TWO VISIONS: Macron v Le Pen

GUIDE: How vote works

- Published21 April 2022