Irpin: Russia's reign of terror in a quiet neighbourhood near Kyiv

- Published

Homes in Irpin were often taken over by Russia's occupying forces and just destroyed

In a corner of the leafy town of Irpin, the brutality of the Russian occupation was clear from the start. The body of a young woman in a red coat would remain in the street for four weeks - lying where she had been trampled not once, but over and over again, under the wheels of Russian armoured vehicles.

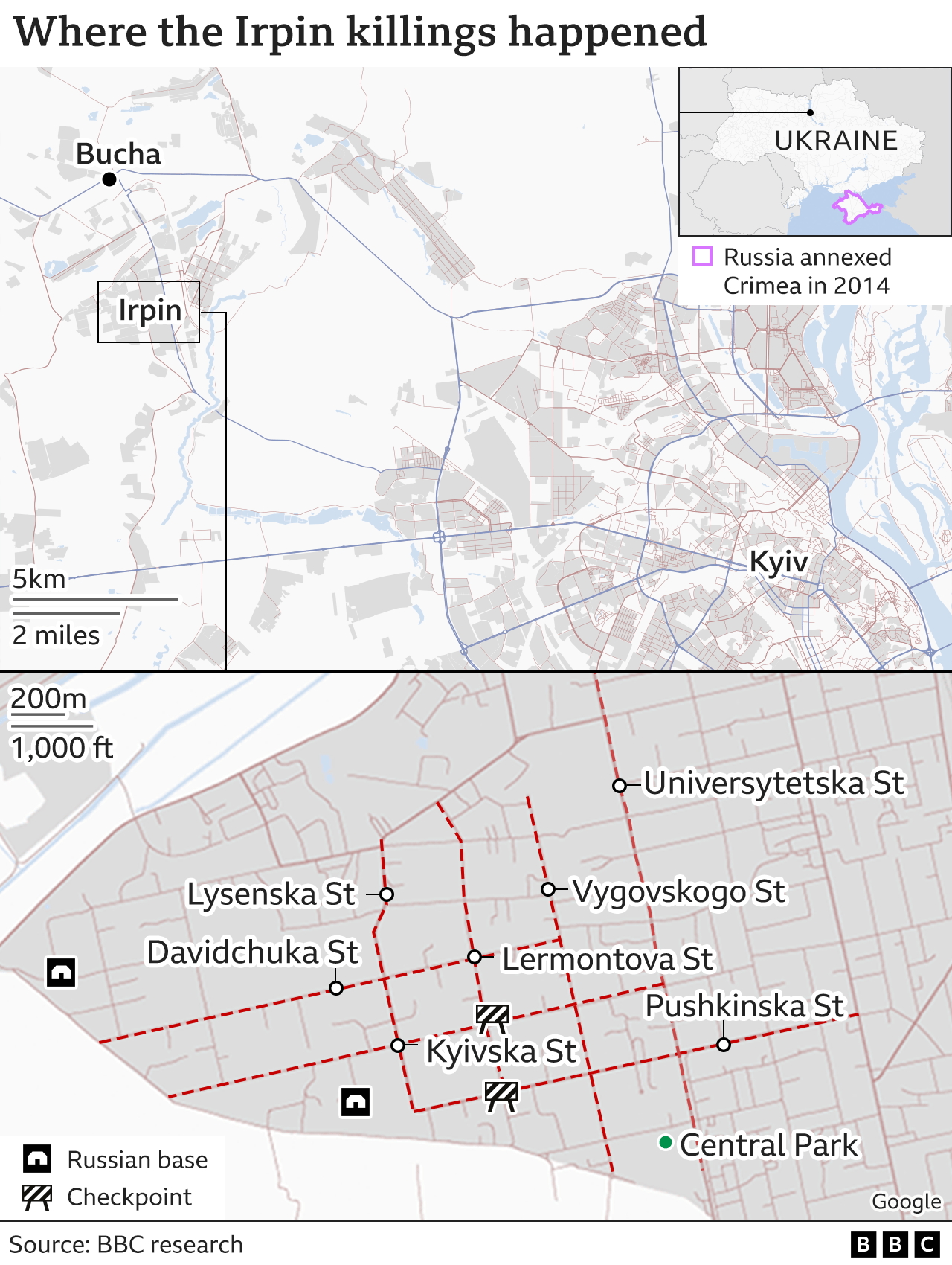

Irpin is on the doorstep of Kyiv, and in early March Russian troops intent on conquering the capital took hold of the town.

Its blown-up bridge and river crossing became known internationally as a risky escape route from next-door Bucha, the scene of many of Russia's alleged war crimes.

In Irpin itself, the bodies of 290 civilian victims have been found and witnesses and prosecutors tell of a month of terror in a narrow zone in the town's south-western quarter. A disproportionate number of victims were women.

Warning: You may find some of the details of this story distressing

Before the war, a handful of streets a short bus-ride away from the capital were a haven for families from the bustle of a busy capital. Now Pushkinska St, Lermontova St, Davidchuka and Vygovskogo all bear the scars of a brutal occupation.

Walking along Pushkinska St shortly after it was liberated, I saw signs of damage to almost every home. Many had been burned to the ground.

But far more terrifying than the destruction were the accounts of violence against civilians, of shootings and summary executions and of people being held by force in a basement.

During the occupation, Pushkinska St became a vital artery - a route to safety for civilians. If you made it out to Universytetska St, then it was a short drive to the ring road and a Ukrainian-held position. All the way down Universytetska St, civilian cars were riddled with bullets and shrapnel.

Close to Central Park, near the junction with Pushkinska, one of the local deputies Artem Hurin says he saw bodies in three cars and an elderly man lying dead on the street.

Eleven units of the Russian army and police are alleged by Ukraine's intelligence and prosecutors to have taken part in the occupation and destruction in Irpin, Bucha and nearby Hostomel.

Russian troops set up firing positions here and in another building used as a checkpoint

Among them was the 141st motorised regiment - otherwise known as the notorious Kadyrovtsi from Chechnya. So was the 234th airborne assault regiment, whose servicemen were once rewarded for taking part in the occupation of Crimea.

Armoured vehicles were stationed behind almost every house in Pushkinska St, according to Hurin, who served as a military volunteer when Irpin was under attack.

Inside this narrow quarter the Russians set up at least two fortified checkpoints with firing positions on Lermontova St, where it meets Kyivska and Pushkinska.

There were at least two bases, at a former children's sanatorium at Lastivka, on the south-western corner of the quarter, and at a big residential complex close by.

Russian armoured vehicles left their base in Vygovskogo St in a hurry - resident Oleksandr Bielokon shows the damage they left behind

The complex was close to the junction of Pushkinska and Vygovskogo St where the woman in the red coat was run over by Russian armoured vehicles.

Town mayor Oleksandr Markushyn and several other residents told the BBC that her body lay there for almost a month.

Her face was unrecognisable from being run over numerous times, said Artem Hurin: "But I saw from her hands she was very young."

On the other side of the street lay the body of an older man: "From his age he could have been her dad."

Ukrainian military volunteers found a plastic card and a handwritten shopping list in the woman's purse and determined that she was probably around 25. "We didn't find any ID on her," said Petro Korol, in charge of gathering bodies for burial.

More than half the victims in this part of Irpin were shot. So many of the dead in this residential quarter were women that the mayor renamed it the place of "women's killings".

On 8 March local residents risked constant shelling and gunfire to bury four people shot by the Russians in a shallow grave beside a bus stop where Davidchuka meets Lysenka St.

"We buried a civilian woman in a pink coat in her 40s with a man. They were killed in the car," resident Tetyana told me. "And two territorial defence volunteers were shot dead in their car." The volunteers were later identified as local residents Dmytro Ukrainets and Sergiy Malyuk.

The bodies of a man and a woman in a pink coat were found in this car after the Russians left

Dozens of the 290 victims are yet to be identified, but prosecutors told me so far they had details of 161 men, 73 women and one child. Many were shot dead in Pushkinska and neighbouring streets. Others died by artillery fire or starved to death.

Most of the suspected war crimes here, as identified by prosecutors and witnesses, happened in mid-March and then in the final days before the Russian withdrawal.

As the Ukrainian army regained control of the outskirts of Kyiv, the Russians became more nervous and began shooting on sight. For residents, misunderstanding an order or refusing to wear a white armband as the Russians insisted could end in death.

"I heard shots in the middle of March beneath the windows of my flat," recalled Ludmila Menkivska, 54, who lives in a residential building on Pushkinska St.

The next morning she saw a woman's body on the street through her window. There was nothing she could do. Had she tried to bury her, she could have been killed herself.

Ludmila Menkivska had already fled war once in 2014

"Every morning for over two weeks I came to my window to check if she was still there. Then every time I looked from my window after shelling I saw her again. I knew nothing about her but my heart was broken. She looked between 40 and 45."

Rather than leave her home, Ludmila decided to stay where she was. No stranger to war, she had fled her home in eastern Ukraine when war broke out in 2014 between the Ukrainian army and Russian-backed separatists.

After the liberation, the woman's body was taken away. She was called Alyona and had a hearing disability, said local resident Mykhailo Kuzmenko, who fears she was killed because she failed to hear the orders of Russian soldiers.

The last week of occupation proved to be the deadliest.

Larisa Osypova,75, had run the local kindergarten for years, raising generations of children. Around 24 March she was shot dead in her backyard with her husband Vadym at 8A Davydchuka St.

They had been sheltering in their house from shelling when shots rang out.

"I saw my neighbour running out to help me," said Kostyantyn Bielkin. "Then I heard a round of gunshots and Vadym crying out 'Larisa! Larisa, then there was an explosion and more shots across the fence."

He was hit three times and remembers nothing more. His neighbours were left unburied for days. Osypova was shot in the face.

Larisa Osypova was known throughout Irpin for bringing up generations of kindergarten children

For 43 years she had run the Vinochok kindergarten, retiring not long before. "People keep calling me and saying: 'We grew up in her hands.' Nobody can believe what happened," says her niece Natalya Dovga.

"Kids used to run up to her immediately," said Vinochok's new head teacher Oksana Ptashnyk. "They never understood she was elderly. For thousands of children she was like a mother, warm, caring and easy-going."

Around the same time, Oleksandr Sheremet and two other men were shot dead in the yard of his apartment block at 9A Vygovskogo St, just around the corner from Larisa Osipova's house. Inside the building a fourth man was killed in his flat.

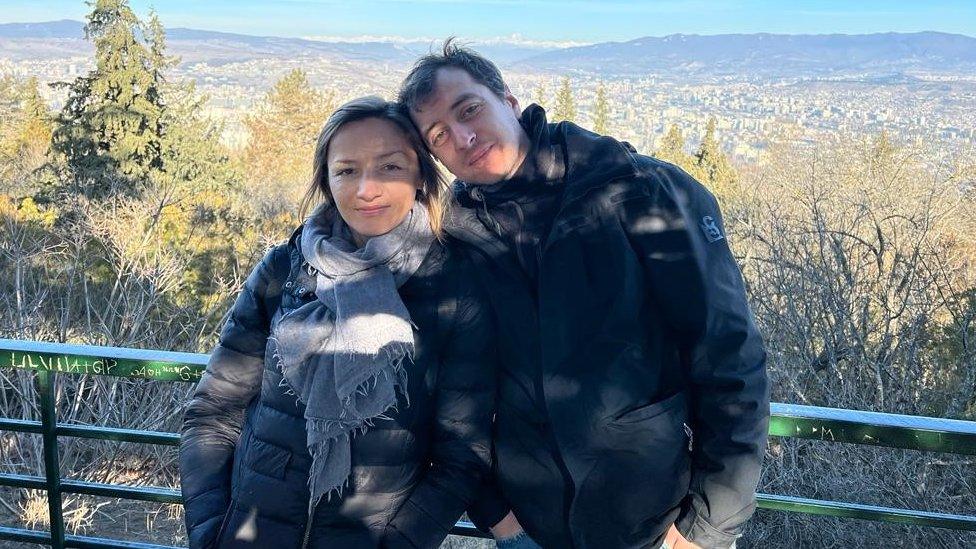

Sheremet, 37, was a children's orienteering coach and had just returned home on the eve of the invasion with a group of children he had taken to the Carpathian Mountains. He had sent his wife Yulia and two of their three children to stay with friends in France.

Yulia Sheremet said her husband Oleksandr had just returned from a trip to the mountains when the Russians invaded

"He could have fled to the west of Ukraine or abroad but he chose to stay to look after his father, the elderly and to help evacuate children," she said.

His father Leonid saw him alive for the last time on 22 March. He next saw his body in Kyiv morgue with five bullet wounds, to his chest, stomach, hand and leg.

Irpin's other summary executions took place around the same time at 42 Davidchuka St.

Two men, one of them an elderly disabled man, were shot. Another man was killed at a sports club in the same block - award-winning boxer and children's trainer Oleksiy Dzhunkivsky,

War in Ukraine: More coverage

Almost next door to the murders in Davidchuka St, Tetiana Levchenko spent the final days of occupation holed up in a basement with other residents, at the mercy of Russian soldiers.

"I was worried they would force all of us to sit on their tanks and act as a human shield."

Her son and daughter had fled with their children but Tetiana, a 54-year-old engineer, had decided to stay hiding in the basement.

"On 23 March the Russian military forced open the door. The next day they forced almost 30 people altogether to stay with us. As they were bringing people in, they killed a male civilian," she recalls.

While she had been in the basement, her elderly parents remained at home. "The Russians blew up two grenades next to them and fired a round of shots into the wardrobe. That was how they made the elderly reveal where the younger people were hiding."

Freedom came finally on 26 March, but Tetiana and the others waited for hours to venture outside, scared that the Russians were still there.

Before the war she had worked as an activist to keep Irpin green and keep the local river clean. "Then the foreigners came in and destroyed our town and our lives."

Few of the buildings in Vygovskogo St were left untouched by the occupation

Visit Vygovskogo and Pushkinska St now and you will find residents in almost every backyard, trying to clean up and rebuild. They have learned to take pleasure in the simple things - like having their electricity, gas and water restored. Those whose homes are still standing can even cook in their own kitchens.

But beneath this facade of normality, the atrocities committed in four weeks in March are never far away.

Pushkinska St resident Oleksandr Bielokon shows me an enormous stain on the road where the body of a woman in a red coat lay throughout the occupation.

"Look, it's still here: the bloody silhouette of a woman run over by Russian tanks."

Related topics

- Published1 April 2022