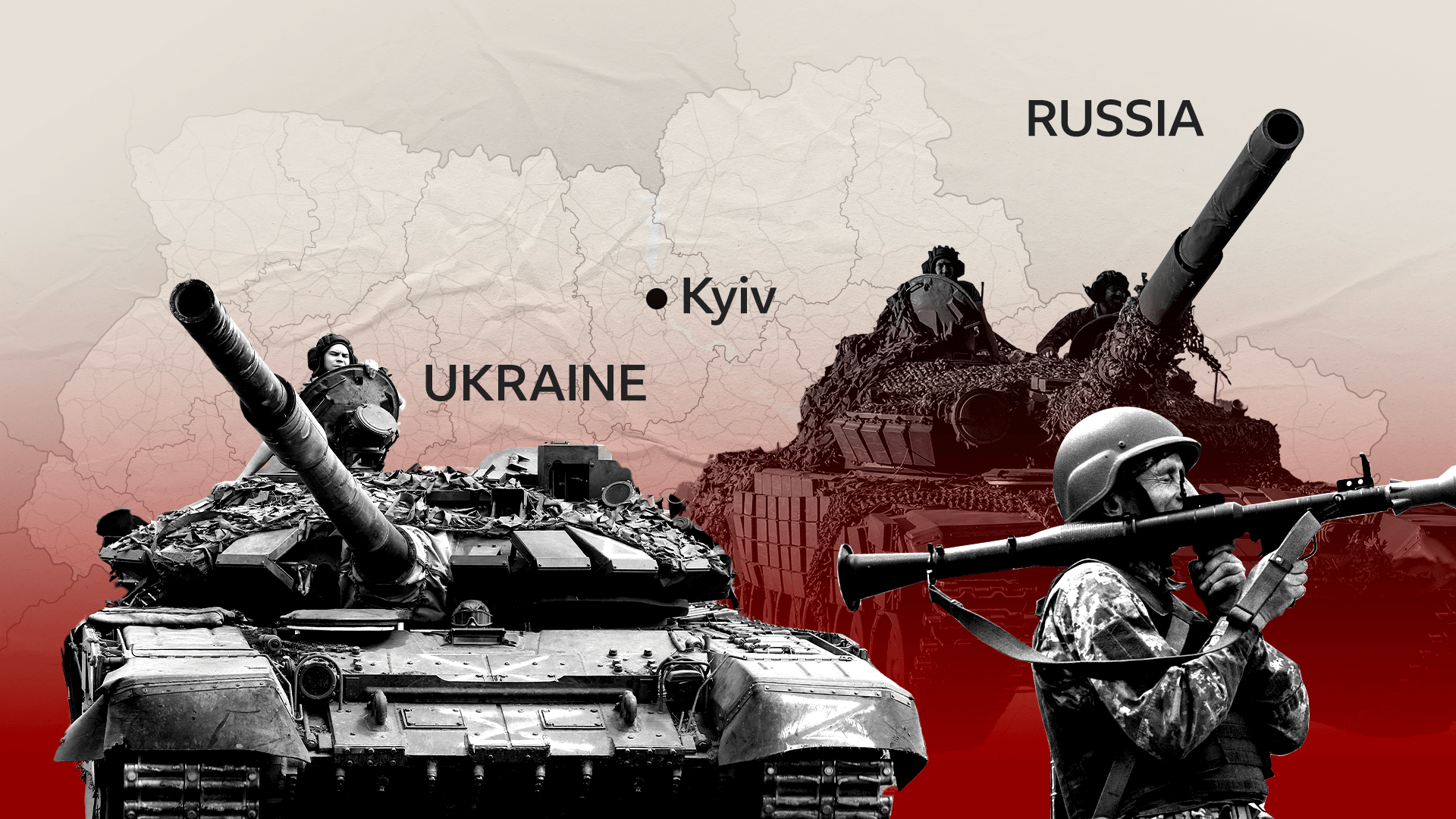

Ukraine war: What Severodonetsk's fall means for the conflict

- Published

Ukraine was forced to withdraw from the city after weeks of Russian attacks

It may have felt like an inevitability, but that does not make the fall of Severodonetsk any less painful for Ukraine.

For weeks it had been the main focus of Russia's invasion, huge artillery barrages and air strikes reducing much of the old industrial city to rubble.

In the end, Ukrainian commanders said defending the ruins would cost too many lives.

In his Saturday night address after Russia had confirmed complete control of Severodonetsk, President Volodymyr Zelensky said it was a difficult day, "morally and emotionally" for his country.

There is no denying it, the loss of the largest city they still held in the Luhansk region does bring one of Russia's key strategic aims one step closer. Ever since the failure of their initial attempts to capture the whole country, Moscow has focussed on taking the wider eastern area known as the Donbas.

That is composed of two oblasts, or regions, Donetsk and Luhansk. Taking one of those would allow President Putin to present his people with a genuine achievement, something he badly needs after the failures of the start of this invasion.

But, taking the entirety of Luhansk is still not guaranteed, even if it is increasingly likely. In Russia's path is the city of Lysychansk, just a few miles away from Severodonetsk - but still in Ukrainian hands.

It is to here that Ukrainian forces are thought to have withdrawn after abandoning Severodonetsk.

To understand why Lysychansk matters, we need to understand the geography of the region and the role it has played in the war so far.

The two cities sit on the Siversky Donets river: it runs through the Donbas and has been the scene of a number of very costly battles for Russia.

In particular, one attempt to cross it a month ago cost an entire battalion tactical group.

Hundreds of men and dozens of armoured vehicles were wiped out by Ukrainian artillery as they attempted to reach the other side.

Indeed, with all bridges between Severodonetsk and Lysychansk destroyed, the curve of the river presents a significant natural barrier to any Russian advance.

Add to that Lysychansk's position on top of a hill, and taking the last Ukrainian positions in Luhansk will be an uphill struggle, figuratively and literally.

The analysts at the Institute for the Study of War release daily briefings on the conflict. In their assessment on 24 June they noted "Ukrainian forces will occupy higher ground in Lysychansk, which may allow them to repel Russian attacks for some time if the Russians are unable to encircle or isolate them".

Russian units were destroyed as they tried to cross the river in May

But it seems that is what Russia is focussed on doing. They are pushing up from the south, claiming to be within visual range of the city.

A spokesman for Russian-backed fighters claimed that the Ukrainian forces' attempt to defend Lysychansk and Severodonetsk was "pointless and futile".

"At the rate our soldiers are going, very soon the whole territory of the [self-declared] Luhansk People's Republic will be liberated," said Andrei Marochko, a representative for the Kremlin-backed army in Luhansk.

"Our troops are already in the city areas of Lysychansk. So we can say we fully control all movements of Ukrainian troops."

The key question is: what is Russia's endgame?

Will they try to take the Donbas, attempting to force Ukraine to accept a ceasefire, annexing the Luhansk and Donetsk regions and redrawing the national boundaries?

This is plausible, especially if Russia's forces are as exhausted as many analysts say.

It could be presented back home as a success. The "special military operation" had "liberated" the Donbas, or what is left of it.

Russia might hope that realpolitik would kick in, with Ukraine being pressured to accept the loss of territory in the name of peace and global stability.

Ukraine would almost certainly reject this, with a frozen conflict the end result.

Alternatively, will President Putin want to finish what he started, maybe taking all of the south, or even making another push for Kyiv?

The BBC speaks to some of the thousands of foreign soldiers who have joined the fight against Russia

Only one man really knows the answer to that, and he's not sharing his plans. But if we want to look for clues as to how this "special military operation" might finish, we need to look at the words of Mr Putin himself.

In a speech at the start of June, he openly compared himself to Peter the Great, equating Russia's invasion of Ukraine with the Russian tsar's expansionist wars some three centuries ago.

It was, implicitly, an admission that his own war was a land grab.

"It seems it has fallen to us, too, to reclaim and strengthen [our lands]," Mr Putin said. Speaking to a group of young entrepreneurs, a smile flickered across his face. It was quite clear he was referring to his invasion of Ukraine.

Russia made crucial errors at the start of this war. They underestimated the will of the Ukrainian people to resist as well as the capability of their armed forces.

Their rush to the capital was met with crushing defeat. It was a painful experience, but also a valuable lesson.

Their slow but relentless march into the Donbas shows they have learned from their mistakes and seem determined not to repeat them.

War in Ukraine: More coverage

KLITSCHKO: 'Russians dying for Putin’s ambitions'

BABUSHKA Z: The real identity of Russia's propaganda icon

READ MORE: Full coverage of the crisis, external

- Published22 June 2022

- Published24 June 2022

- Published22 June 2022