The sole survivor of a Russian shooting - he lived by playing dead

- Published

Ivan Skyba

Taxi driver and father of four, Ivan Skyba, found himself defending a suburban street at the start of the war. He narrowly avoided death at the hands of the Russians. All the other Ukrainian men with him were not so lucky. Prosecutors are treating what happened in the small city of Bucha as a war crime. Fergal Keane has been to meet Ivan, the sole survivor.

There is the urge to breathe out. Just one big exhalation to relieve the pressure. But Ivan knows it will be the death of him if he does. The temperature is just above freezing. Warm breath rising into cold air will create a small fog and alert the killers. They are already checking the bodies of the men they have just shot, making sure, firing a final bullet where they see any sign of life. He hears one of the Russians say: "That one is still alive!"

Ivan wonders if they are talking about him? Maybe it is one of the others. Still, he prepares himself for the bullet. He is already bleeding from a wound in his side. The other Russian says: "He will die by himself!"

But then there is a shot. It strikes somebody else. A man fights different urges in such moments. The bullet wound in his side is agonisingly painful. But crying out would be fatal. All of this will come back later in dreams. But for now, he will lie among the dead. He will be as still as his murdered comrades.

I meet Ivan Skyba in a small village in rural Poland where he has found shelter for his family. He has a job. The kids are living in a place without fear. The warm weather has arrived and in the evenings the family walk to a local park where Ivan fishes in the lake. The bruises on his face and body have healed. But at night, after everybody else is asleep, the wounds of memory are open. Ivan Skyba is the man who came back from the dead.

When it all started in the early hours of 24 February, Ivan was driving his taxi in Kyiv. He heard explosions. Ivan struggled to believe it was actually happening. "I didn't imagine it coming," he says.

The dispatcher called and said all taxis were to return to base. Forty-three year old Ivan had been doing whatever work he could find to support his wife and four children. He drove the cab and sometimes worked as a building renovator. His first thought that morning was to get the family's identification documents. If they were going to have to flee, they needed passports. He quickly drove the 40km towards Brovary where they lived - and from there to Bucha where his wife and children were visiting her mother. That was where the family would stay until they could make a plan.

"Different rumours were circulating that [the Russians] were approaching Bucha. We started arranging shelters in the cellars, bringing things there."

Ivan (l) with his friend Svyatoslav Turovsky and Ivan's daughter Zlata

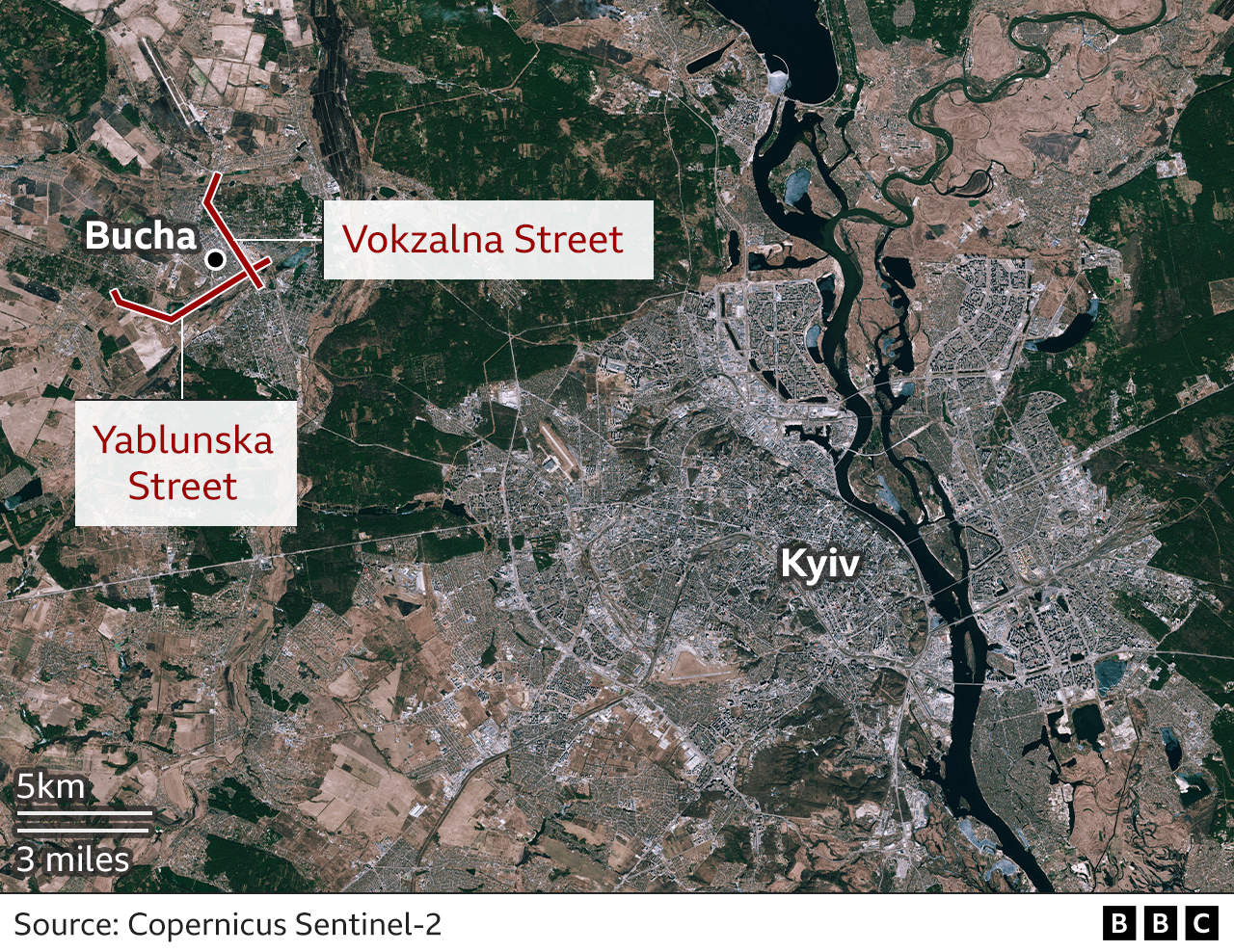

Three days later, on 27 February, the Russians arrived nearby. Almost immediately they suffered a devastating ambush by Ukrainian artillery. A column of Russian airborne troops had taken up position on Vokzalna Street when the shells came screaming in. They retreated temporarily. But they were angry, convinced some locals had told the Ukrainian military of their location.

By now, across Ukraine, people were mobilising to defend their communities. Bucha was no exception. Ivan Skyba and his friend, Svyatoslav Turovsky, the godfather to his two-year-old daughter Zlata, heard that some men who had fought in the eastern Donbas region against the Russian-backed separatists were forming in Bucha a unit of Ukraine's Territorial Defence Force, a militia to protect local communities in time of war. The two men joined up.

"We were doing duty at checkpoints, checking documents and making sure people didn't carry arms," says Ivan. "We were helping to organise people's safe passage out because we knew the area."

Ivan's unit was poorly armed. They had one rifle, a grenade and a pair of binoculars to share among nine men. He and his comrades worked shifts on a checkpoint on Yablunska Street. In Ukrainian it means "the street of the apples", because of the trees that line much of its nearly 6km length. In peacetime, it is a pleasant place with a lake for fishing. Some of the houses back on to fields and orchards.

It is also the site of an old office complex, built in the Soviet era, part of which has been transformed into workspaces for local businesses. These quarters at 144 Yablunska Street would become a Russian base notorious in the story of the war's brutality.

By early March, Ukrainians were fleeing the country in their hundreds of thousands. Ivan and his wife decided the family should try to shelter in Bucha for the time being. He describes the atmosphere among the men as one of defiance.

"There was no fear. No fear. There was a desire to unite, to get together. We were on our feet all the time. When we were off duty, we would distribute food around cellars to those who were taking shelter there, the women and children. There was no time to be afraid."

That changed dramatically on 3 March. The Russians returned in force "in the second half of the day, around lunchtime".

Immediately, Ivan and the others began directing cars away from the direction of the Russian advance. There was indiscriminate firing. Rockets were landing. He saw a white Renault being struck and a woman and her children trapped inside the burning car. There were eight men at Ivan's checkpoint and with the Russians rapidly approaching they decided to try to hide. Directly opposite the checkpoint, at number 31 Yablunska Street, was Valera Kotenko's house. The 53-year-old had given them hot drinks and food. He offered shelter now. Soon the Russians were outside.

Ivan at the checkpoint outside 31 Yablunska Street

"We could hear them and the movement of their equipment. We were surrounded," says Ivan. The men whispered to each other. They could not run. The Russians had thermal imaging detectors that would surely pick up any attempt to escape at night. The men had already ditched their few weapons and now decided on a cover story - if the Russians found them they would say they were builders working in the district and had been sheltering from the fighting.

They texted wives and girlfriends. One of the men, Anatoliy Prykhidko, aged 39, called his wife Olha that evening - 3 March - and whispered "that he couldn't speak because he could be heard. It was so quiet. He said they were in hiding."

The following morning, Yulia, the wife of Andriy Dvornikov, a delivery driver, received a message saying: "We have been encircled, we are sitting here, but I will be getting away from here as soon as there is an opportunity." He told her to delete all messages and photographs from her phone. And he told her that he loved her.

"At 10am, [Anatoliy] sent me a message saying 'we are still sitting tight.' That was his last message," says Olha Prykhidko

With tears streaming down her face, Olha Prykhidko, tells me of her last communication from Anatoliy on the morning of 4 March: "At 10:00, he sent me a message saying 'we are still sitting tight.' That was his last message."

Less than an hour later the Russians broke in.

Ivan Skyba remembers beatings and shouted questions. Mobile phones and shoes were confiscated. By 11:00 two different sets of CCTV images captured the men being led across and then down Yablunska Street towards number 144. Each had one hand on the belt of the man in front and the other on their own head. They were lined up against a wall next to the Russian base and made to kneel. The Russians forced their shirts and sweaters over their heads so that they could not see . They were beaten with rifle butts and verbally abused. According to Ivan they shouted: "You are the Bandera fighters (an anti-Soviet nationalist group in World War Two). You wanted to burn us with Molotov cocktails! We'll burn you alive now!"

CCTV shows the men being marched at gunpoint to the location where they were killed

Ivan says the Russians decided to intimidate the others by shooting 28-year-old Vitaliy Karpenko, a worker at a co-operative store. After this, a younger man in the group panicked and told the Russians that all of them belonged to the Territorial Defence Unit. The beatings intensified.

Ivan Skyba and another man, Andriy Verbovyi, a father of one and a woodworker, were brought into the building. In the interrogation that followed, Ivan had a bucket placed over his head and was made to bend and lean against the wall. Bricks were piled, one after the other on his back, until he collapsed. He was beaten again and a brick was repeatedly smashed against the bucket. At some point he heard the police tell Andriy Verbovyi that they would shoot him in the foot. There was a shot. After that he didn't hear Andriy any more.

Ivan was then led back out of the building to join the other men. Some of what took place was witnessed by local residents who were ordered to gather by the Russians in front of number 144, but kept separate from the arrested men. Lucy Moskalenko remembers a Russian officer telling her to cover her daughters' eyes because they would see things they would never forget. "He told us, 'Don't look at those people lying on the ground. They are not humans. They are absolute dirt. Dirt. They are not human. They are beasts.'" Her sister, Irina Volynets, had accompanied Lucy. Both recall the noise of the Russian armoured vehicles, the sound of shelling, and how the dogs of the neighbourhood were fighting with each other. It was as if a madness had descended on the place.

Then Irina had a shock. She saw that her old classmate, Andriy Verbovyi, the boy who had sat beside her from kindergarten, and all the way up through school, was lying bleeding on the ground. Only a few weeks before, they had walked home from the shopping centre together. There was a sheet thrown on the ground near him. "He was lying there, all twisted from cold. He was looking straight at me. We looked into each other's eyes," she says. Irina wanted to go and cover her old friend with the sheet, anything that might make him warmer. But she did not. "Was she too afraid?" I ask.

"It was not so much fear as despair," she replies, "and I was really confused at the time, and couldn't seem to grasp how it happened, and why my classmate was lying there on the ground." Everything was happening so fast. Besides, she had just seen that her son Slavyk was among the line of men. He had been captured separately and beaten, before being brought to join the others. Waiting in the line Slavyk saw blood on the ground nearby, and heard the Russians talking about a wounded man. This was almost certainly Andriy Verbovyi. "I heard them talk among themselves to finish him off because he wouldn't make it," recalls Slavyk. He began to fear for his own life.

Irina found an officer and pleaded for Slavyk's life. The soldier listened. Then he called over a Ukrainian informer - possibly the arrested man who had cracked after the shooting of Vitaliy Karpenko - and asked him: "Is he one of them?"

"No," came the reply. Slavyk was released to his mother. The residents were told to go home, but Irina remembers an ominous feeling as she left. "I was afraid horrible things would happen."

On the following day, 5 March, Andriy Verbovyi's wife, Natalya, sent him a message.

"Where are you? Your [good luck] chain is with me, the amulet as well. I am protecting you from all bad things. We are praying for you. We are waiting for your call. Write us at least two words."

By then, Andriy was dead.

Ivan Skyba sensed time was running out. By late afternoon on 4 March, two of the eight men captured with him had been shot dead. "The Russians started talking between themselves as to what they would do with us. The conversation was as follows: 'What shall we do with them?' The second man says, 'Finish them off, but just take them out, so that they wouldn't be lying here.'"

The remaining men were led around the corner into a small courtyard. From under the edge of his clothing Ivan saw the body of a man lying on a small concrete platform. He had clearly been shot earlier. The Russians began taunting their victims. "They were enjoying the execution, using swear words, saying, "That's it. It's kapooey (death) for you!" Ivan recalls a final exchange of words with his comrades. "We said goodbye to each other. That was it." Among those to whom he bade farewell was Svyatoslav Turovsky, the godfather of his daughter.

According to Ivan, Anatoliy Prykhidko suddenly decided to make a run for it but was shot straight away. Then the Russians opened fire on the others. "I felt a bullet go into my side," Ivan remembers. "It wounded me and I fell."

Ivan Skyba's bruised face and bullet wounds on his torso

Ivan cannot remember exactly how long the Russians stayed, but it was more like minutes than hours. When he sensed they were gone he risked a glance from under his jacket. The courtyard was empty of life. Now was his chance. He reached out towards a pair of feet near him - those of the dead man he had noticed when they first entered the courtyard. He pulled off the man's shoes to put on his own exposed feet. He then crawled to a fence and dragged himself across into nearby gardens. There was another fence to cross before he made it into a house abandoned by its owners during the shelling.

What followed was another terrifying ordeal. Inside the house, Ivan treated his wound with some antiseptic liquid he found in the bathroom and changed into clothes left behind by the householder. He wrapped himself in a blanket and tried to sleep. But he was disturbed by voices. Russian voices. It turned out that several Russian soldiers were also resting in the house.

"They saw me and started asking me who I was and what I was doing there." He persuaded them that he was the owner of the house and that his family had been evacuated. His wounds, he explained, were the result of shelling. The soldiers believed his story but they told him he couldn't stay where he was. Instead, they said they would take him to their base for medical treatment. Back at 144 Yablunska Street. "I was terrified what would happen next - from one captivity into another."

But Ivan's luck held. At the base, combat medics treated his wounds. If the troops who shot him were still around, they either did not see him return, or did not recognise him. He was placed with civilians sheltering in the bunker of the building. After several days, they were allowed to leave.

The bodies of the murdered men who had been defending Bucha with Ivan were left lying in the courtyard, where the Russians dumped rubbish, for the remaining month of the occupation. Ivan found his family, still sheltering from the war, at home. They were able to flee Bucha, and eventually Ukraine into Poland, but not the legacy of the terrible hours at 144 Yablunska.

The office building at 144 Yablunska Street where the killings happened

Military defeat forced the retreat. Harried by Ukrainian forces the Russians pulled out of Bucha on 31 March and headed north to the border with Belarus.

The invaders left behind numerous traces of their presence. From the banal - obscene graffiti scrawled on the walls - to the potentially significant. We found a soldier's military-issued debit card on the floor of 144 Yablunska, and traced him to Pskov in north-western Russia, a major base for airborne forces. Other journalists found evidence leading to the same units - the 104th and 234th Airborne Assault regiments.

A Bucha resident found Ivan Skyba's mobile phone, left behind by the Russians as they retreated. It contained records of calls made to several numbers in Russia. The records don't link any of the callers directly to the massacre. The phone might easily have been passed around among a large group of soldiers. But the call records could help narrow down the search for perpetrators to smaller units within the regiments present when Ivan and the others were shot.

The killings at 144 Yablunska Street and elsewhere in Bucha are the focus of a huge war crimes investigation by the International Criminal Court and Ukraine. The Ukrainian investigation is led by a police lawyer who, until recently, was best known for investigating cases of brutality within the country's police force. Walking me around the crime scene, Yuriy Belousov is hopeful the perpetrators will ultimately face justice.

"These Russian soldiers who have committed this crime, they could be captured somewhere," he says, pointing to the recent trial of a Russian prisoner of war accused of murdering a civilian near Kyiv. But the big targets of the investigation are President Putin and the Russian military and political elite.

"It was planned in advance," Mr Belousov says. "It was instructed from the top how to behave. So the suspects would be top of the top, the guys who actually launch the war, let's say. It's like a chain of people whose decisions led to the invasion of Ukraine."

Barring a change of regime in Moscow, any imminent prosecution seems highly unlikely.

Ivan Skyba with Fergal Keane in Poland

If there are prosecutions, Ivan Skyba will be a vital witness. For now, he works with the Polish man who has given the family shelter. The Russians seem physically far away. But there is the terror that comes at night. "You wake up because you are anticipating that shot in your head. I have this feeling. It comes like a wave."

When we walk to a nearby lake in the evening, I notice that a teenaged boy has joined the family group. He plays with Ivan's son who is just a few years younger. Ivan tells me that the teenager is the child of his murdered friend and godfather to his daughter, Svyatoslav Turovsky. The boy and his mother moved to Poland with the Skyba family.

It is a perfect early summer's evening - the boys fishing, Ivan leaning against a tree and looking on, his wife shepherding their young daughter away from the water's edge. But for Ivan and his family, for their friends the Turovskyis, for all the families of the men of 144 Yablunska, Russia's invasion and the massacre it unleashed has changed everything.

I remember the words of Olha Prykhidko, whose husband Anatoliy tried to run for his life, and whose grave she visits every day with two cups of coffee, one for him and one for her. "When no-one can hear me," she says, "I call him by his name." Day after day she calls to him, from silence to silence, into the emptiness made by war.

Additional reporting by Sofiia Kochmar-Tymoshenko, Viacheslav Shramovych, Rostyslav Kubik, Alice Doyard and Orsi Szoboszlay

I Call Him By His Name' presented by Fergal Keane is available on BBC iPlayer from 16 July.

War in Ukraine: More coverage

STOLEN GRAIN: Tracking where Russia takes Ukraine's grain

ANALYSIS: Why Russia couldn't hold Snake Island

FACT CHECKED: Russia's claims about shopping centre attack

READ MORE: Full coverage of the crisis, external

Related topics

- Published9 April 2022

- Published13 April 2022

- Published4 July 2022

- Published30 June 2022

- Published25 June 2022