Mikhail Gorbachev: Remembering a warm-hearted and generous man

- Published

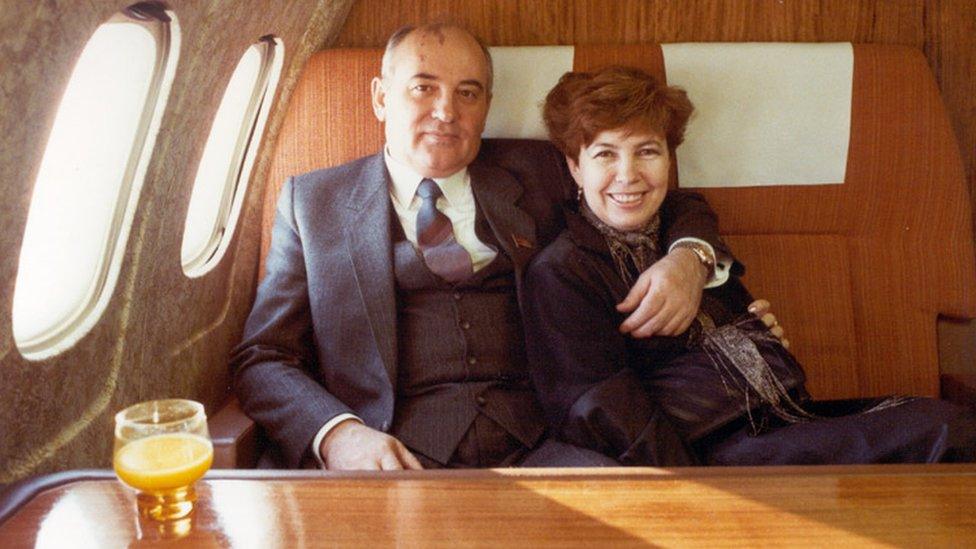

Mikhail and Raisa Gorbachev were married for 46 years before her death in 1999

It's March 2013 and I'm interviewing Mikhail Gorbachev at his Moscow think tank. After half an hour the former Soviet leader announces 'Vsyo!' ('That's your lot!'). He gets up, but appears in no hurry to say goodbye.

So, we continue to chat. Mr Gorbachev has just published the latest volume of his memoirs, which he's dedicated to his late wife Raisa. She died of leukaemia in 1999. They'd been married for nearly 46 years and from the tender way in which he talks about her it's clear that Gorbachev misses her deeply.

He shows me the book. Page one features an entry from Gorbachev's diary, a year after Raisa's death:

"My life has lost its principal meaning," he writes. "I have never had such an acute feeling of loneliness."

But Gorbachev's eyes light up as he points out pictures of Raisa in the book: the holiday snaps, the family photos, pictures of her accompanying him on official trips abroad. And his two favourite images: matching portraits of Mikhail and Raisa before their wedding day in 1953. They look like Hollywood film stars.

While Gorbachev and I have been looking through the book, our camera operator Rachel has been examining the grand piano in the corner of the room.

"Can you play that?" she asks Gorbachev.

"No need to, it plays itself!" he replies.

We all laugh. But he isn't joking. Gorbachev walks over to it, presses a button and the piano keys burst into life all by themselves.

Watch: Steve Rosenberg and his unlikely musical partner - Mikhail Gorbachev

"That's Chopin," he says and, with a cheeky grin, he mimes like a maestro and pretends to be playing the music himself. Then he flicks a switch and the instrument falls silent.

"Of course, you can also play it like a normal piano," he points out. "Can any of you play?" he asks. I tell him I can.

"Please, sit down, play something," Gorbachev says.

I didn't expect that. I have to think fast. What should I play? What tune would a former superpower supremo appreciate? Back in the USSR, perhaps? Or Thanks for the Memory? I play safe and launch into the Russian classic Moscow Nights.

And, as I'm playing, something even more unexpected happens. Mikhail Gorbachev starts to sing along. And he's good… in tune. We get to the end and I ask him which other songs he likes. Gorbachev requests the Soviet wartime melody Dark is the Night. It tells of a soldier on the frontline who is thinking about his dear wife back home.

"In the dark night," sings Gorbachev, "I know that you, my love, are awake,

"Sitting by the crib you're secretly wiping away a tear;

"How I love your deep gentle eyes,

"How I want to press my lips to yours."

Then, the man who helped to end the Cold War smiles: a broad, beautiful smile.

"Raisa loved my singing," he says.

In that one short sentence, Mikhail Gorbachev has revealed more about himself than in a whole interview.

There are many people in Russia who criticised him for the way he governed the country; who blamed him for the collapse of the Soviet Union. But after those words - and that smile - he came across as a warm hearted, decent man, who was still deeply in love with his wife and desperately sad that she had gone. Raisa was everywhere: in his books, in framed portraits on his office wall... and in the music.

What do people from Mikhail Gorbachev's home town make of his legacy?

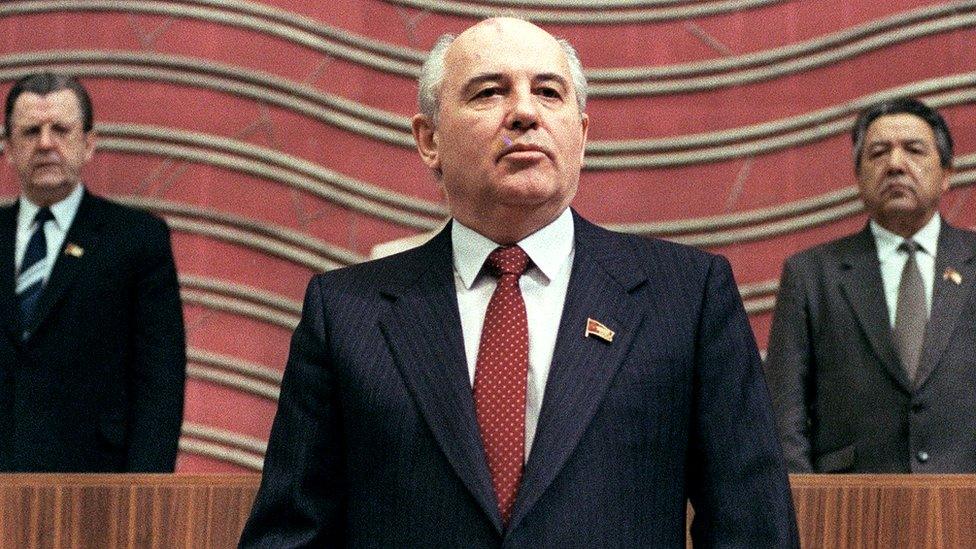

I first met Mikhail Gorbachev in May 1996, more than four years after the demise of the USSR. He was attempting a political comeback and challenging Boris Yeltsin in Russia's presidential election. At the time I was an assistant producer for CBS News. Our camera team was following him on the campaign trail in southern Russia.

I was excited to meet the man who, a decade earlier, had inspired me to take Russian at university. In the mid-1980s Mikhail Gorbachev had burst on to the political stage with his calls for perestroika (reconstruction) and glasnost (openness). He was the kind of Soviet leader the world had never seen. He was young, relaxed. He seemed determined to build better relations with the West and to reinvigorate the stagnant Soviet economy.

By the time he left office, the Soviet Union no longer existed.

On that campaign trip in 1996, one evening Gorbachev invited our TV crew to join his table in the hotel restaurant. Suddenly the band struck up with a familiar tune:

"Yesterday, all my troubles seemed so far away.

Now it looks as if they're here to stay…"

It felt so appropriate. In the election Gorbachev would receive just 0.51% of the vote.

He had lost power - and had failed to regain it. But there was one thing Mikhail Gorbachev still had: his sense of humour.

The following month the cameraman I'd worked with on the Gorbachev trip completed his Moscow attachment. Victor Cooper was a larger-than-life Texan who made everyone around him smile. He hadn't picked up much Russian, but one of the few sentences he'd learnt was a belter:

"Samoe glavnoe eto kooritsa!"

Which means: "The most important thing is chicken!"

It came in handy. Whenever Victor got pulled over by the Moscow traffic police, he'd wind down the window of his Suburban and declare in Russian with a big Texan twang: "The most important thing is chicken!"

The dumbfounded officer would normally wave him on.

At work I was given the task of producing a "goodbye video" for Victor containing goodwill messages from friends and colleagues in Moscow. On the off chance, I called Gorbachev's assistant. Would President Gorbachev consider contributing a video message?

The response was swift: "He'll do it."

With another cameraman, I drove to Gorbachev's office.

"What would you like me to say?" he asked.

I explained how much cameraman Victor had enjoyed meeting him. I also happened to mention Victor's poultry knowledge of Russian. Gorbachev turned to the camera and recorded a heartfelt monologue, which concluded with these words:

"Victor, as you well know, the most important thing is chicken!"

I had to pinch myself. Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev, formerly one of the most powerful men on the planet, had just sung the praises of poultry. What a good sport. When Victor Cooper saw the video, he was astonished and deeply moved.

Mikhail Gorbachev with Steve Rosenberg (front left), Victor Cooper and the CBS team

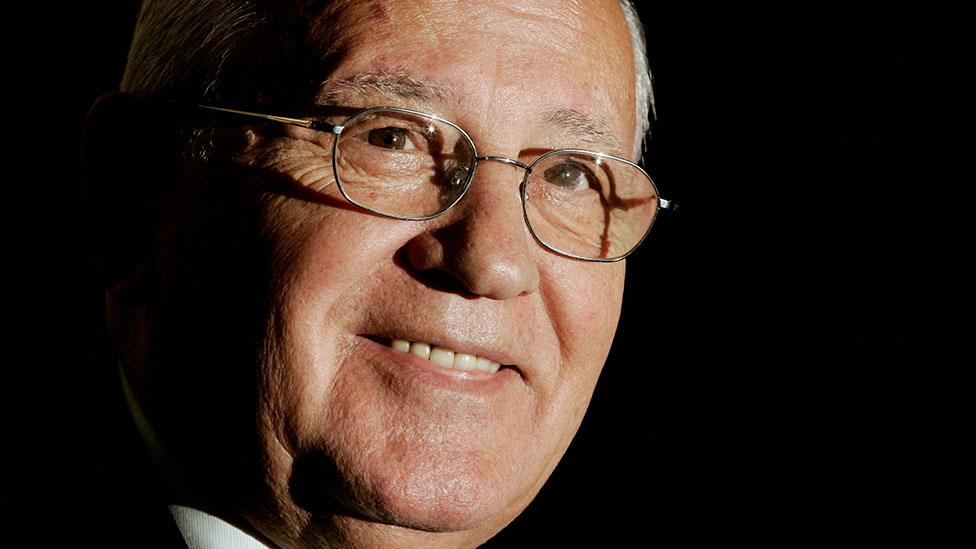

It was a very different Gorbachev I encountered in 2019. This would be the fifth and final interview he gave me. There was a sadness to him I hadn't seen before. As if he sensed that his achievements were being rolled back; that Russia was re-embracing authoritarianism and East-West confrontation was returning.

In the interview, Gorbachev recalled his early days in power.

"When I became General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party, I travelled to towns and cities across the country to meet people. There was one thing everyone talked about. They said to me: 'Mikhail Sergeyevich, whatever problems we have, whatever food shortages, don't worry. We'll have enough food. We'll grow it. We'll manage. Just make sure there's no war.'"

By now, there were tears in Gorbachev's eyes.

"I was stunned. That's how people were. That's how much they had suffered in the last war."

Mikhail Gorbachev wasn't perfect. No leader is. But this was a man who cared deeply about averting a Third World War. And he cared deeply about his family.

For both those things I will remember him warmly.

Related topics

- Published13 December 2016

- Published30 August 2022

- Published4 November 2019