Ukraine's shadow army resisting Russian occupation

- Published

Ukrainian resistance fighters use drones to spot targets for the military

As Ukraine's military steps up its strikes on Kherson, hinting at a new offensive to recapture the region, there is another force working alongside. They are Ukraine's shadow army, a network of agents and informers who operate behind enemy lines.

Our journey to meet the resistance fighters takes us through a landscape of sunflower yellow and sky blue to Mykolaiv. The first major town on Ukrainian-controlled territory west of Kherson, it has become the partisans' headquarters on the southern front.

Driving through military checkpoints, we pass giant billboards showing a faceless, hooded figure alongside a warning: "Kherson: The partisans see everything." The image is designed to make the region's Russian occupiers nervous and boost the morale of those trapped under their rule.

A billboard warns collaborators "Kherson: The partisans see everything."

"The resistance is not one group, it's total resistance," the man standing in front of me insists, his voice slightly muffled by a black mask he's pulled up from his neck so I can't see his face as we film him, in a room I can't describe so that neither can be found.

I'll call him Sasha.

Shortly before this war, Ukraine bolstered its Special Forces in part to build and manage a resistance movement. It even published a PDF booklet on how to be a good partisan, with instructions on such subversive acts as slashing the tyres of the occupier, adding sugar to petrol tanks or refusing to follow orders at work. "Be grumpy," is one suggestion.

But Sasha's team of informers have a more active role: tracking Russian troop movements inside Kherson.

"Say yesterday we saw a new target, then we send that to the military and in a day or two it's gone," he says, as we scroll through some of the many videos he's sent from the neighbouring region each day. One is from a man who drove past a military base and filmed Russian vehicles, another is from CCTV footage as Russian trucks pass by, daubed with their giant Z war-marks.

Sasha describes his "agents" as Ukrainians "who have not lost hope in victory and want our country to be freed".

"Of course they're afraid," he says. "But serving their country is more important."

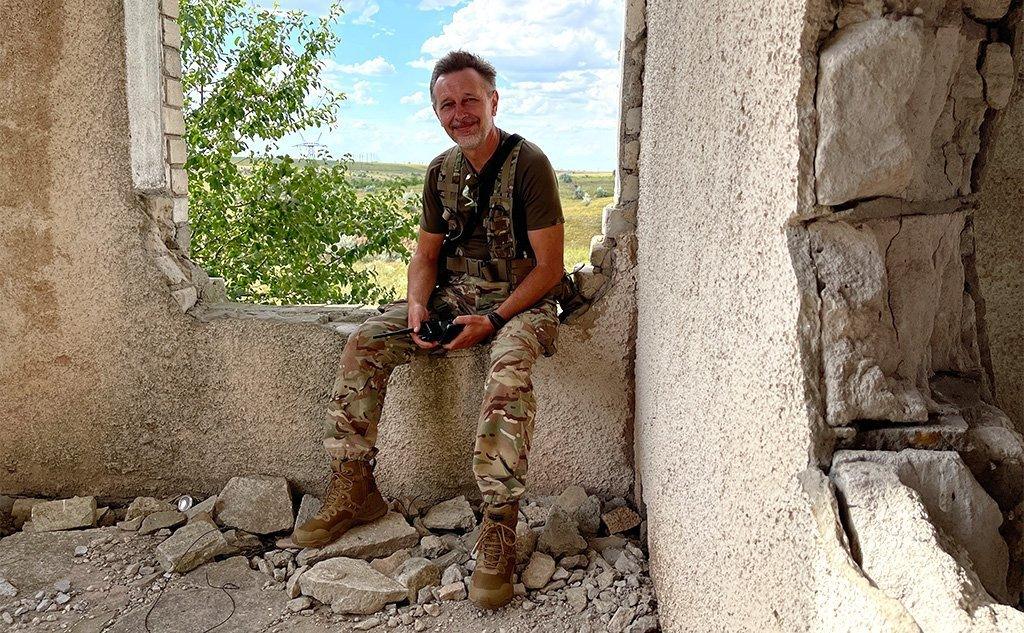

Working alongside Sasha are a team who fly drones into Kherson to spot targets for the military. Civilians, not soldiers, all are volunteers and they fundraise on social media to pay for their expensive kit.

The man in charge cultivated decorative plants before the war, but Serhii tells me he joined the fight to free the south after seeing the bodies of civilians executed in Bucha during the Russian occupation there. "I couldn't just stay at home after that," he says. "I didn't know what else I could do or think of, while this war is going on."

The task he chose instead is extremely dangerous. His team of four get shelled by the Russians every single time they go out, though no-one has been killed. "I know to some extent it's a matter of chance," Serhii shrugs, and breaks into a soft smile. "But at least if it happens to me, then I will know it was for a cause."

Serhii joined the resistance in the south after the massacre in Bucha

The partisans are fighting to prevent Russia's hold over Kherson becoming permanent: to block a referendum that Moscow appears to be planning to stage. Russia has already introduced the rouble and its own mobile phone networks to the region and is pumping its propaganda from state-run TV channels into Ukrainian homes. Local journalists have either fled, or gone to ground.

The acting head of the region, Dmytro Butrii, now exiled to Mykolaiv and a small back office protected by sandbags, insists that a vote on joining Russia would be a sham, a "total fake" and unrecognised by any "civilised" government.

These days, that wouldn't matter much to Moscow.

For Russia, the region is strategic: it's the source of water for Crimea, which it annexed illegally in 2014, and the last section of a much-discussed 'land bridge', or stretch of territory that links Russia-proper to the peninsula.

The exiled head of the region, Dmytro Butrii, says a referendum would be a sham

Some locals have switched sides to help the Russians. So Sasha's team are building a database of those "collaborators", using information from the inside. "It's so that no one can claim later that they were with the resistance," he explains.

But it's also for intimidation. Partisans are encouraged to stick threatening posters outside the collaborators' homes with designs that include the person's face and a coffin, or a "Wanted" poster offering big rewards for their death. The activists then photograph the results to send to Sasha.

"There's a lot of graffiti. People write things like 'stuff your referendum' as well as sticking up their posters," Sasha describes his latest reports from Kherson. "It shows how many people are not afraid: in a city with military patrols everywhere, they manage to print leaflets then walk round with glue when they could be stopped at any moment and things would end very badly."

There has been a spate of assassination attempts against those who've joined the Russians. A blogger was shot, an official in the Russian-installed administration was killed and others have been injured in car bombs. The most prominent figures to switch sides now wear body armour as a matter of course. The men I meet all say they have nothing to do with the attacks, but they have no sympathy either.

"Other than the word traitor and scum, I have no other words for them," Sasha shrugs. "They're our enemy."

Vladimir Putin still claims his invasion of Ukraine is a "liberation" operation but in Kherson, his troops rule through force and fear.

Since Russian forces occupied the region in March, hundreds of people have been detained, many of them tortured. Some have disappeared, unheard of for weeks. Others have been discovered dead or returned to their relatives from Russian custody in body bags.

Sources inside the city describe soldiers patrolling the streets and buses stopped at random for everyone inside to be checked. The slightest hint of support for Ukrainian rule, as little as a message or photo on your phone, can get you arrested.

Every time Oleh smiles in the mirror, the gaps in place of his teeth are a reminder of the beatings he endured by his Russian interrogators. He tells me they also broke seven ribs - three still haven't mended. His name is not really Oleh, but he's asked me not to reveal his identity.

A member of the resistance, he witnessed the torture of another prisoner, Denys Mironov, who then died in Russian custody.

Denys Mironov

Oleh talks in chilling detail about what happened after 27 March when he and Denys were snatched from the street: he describes constant beatings in the first hours involving electric shock, suffocation and death threats. He's sure his interrogators were from the FSB security service.

At some point, his spirits fell so low that he contemplated ending his life, even attacking a guard so they would shoot him.

"They were looking for Nazis, so they beat me because I was bald. They reckoned they'd caught a damn Nazi," he answers, when I ask what information his captors had wanted. "When they stripped me, they saw I had Simpsons underpants so they said I was an American agent and punished me for that."

A month earlier, when the Russians invaded, Oleh and Denys had joined the territorial defence, Ukraine's volunteer army. But much of the military melted away with the first explosions and Kherson's remaining forces were quickly overwhelmed. So the men became partisans, working against the Russians from the inside.

"We got information on where their forces were based, and when they were on the move, and we passed that on to the military," Oleh explains, adding that he was involved in a lot more activity that he can't talk about.

Another partisan I met described helping Ukrainian forces escape in boats across the Dnipro when they were surrounded - and stealing weapons from the Russians. "I'll tell you the rest when we win," he laughs when I press him for more.

Denys, a 43-year-old with a wife and son - and a fruit and veg business before the war - began driving a bread van around Kherson, handing out food and scouting for intelligence as he went. He and Oleh were also collecting weapons, preparing to join the battle to liberate Kherson as soon as Ukraine launched the counter-offensive that everyone expected.

Instead, the two men were detained and tortured.

I asked Russia's FSB to explain what happened to these men and others. They didn't respond.

It was the middle of the first night before Oleh saw Denys again, and by then he could barely walk and was struggling for breath. Even so, the guards beat him some more. "They hit him in the groin, then the face, then two men with batons took down his trousers and started to beat him near his kidneys," Oleh says, recalling how the tape holding a bag over his own head had worked loose enough for him to see.

"It was clear his lungs had been punctured and he'd been really badly hurt," he says. "But if he'd been helped in time, his death could have been avoided. It's awful."

On 18 April the men were transferred to a facility in Crimea and the next day, Denys was finally taken to a military hospital where Oleh was sure he would recover.

The first Denys Mironov's family knew of his death was over a month later, when he was returned to Ukraine as part of a body swap.

Many people left Kherson for safety soon after the Russians seized control. The government in Kyiv recently urged others to evacuate, warning that a military operation to retake the region was imminent.

But getting out isn't easy.

Russian officials limit the number of vehicles crossing the frontline and only permit one route into Ukrainian-controlled areas, the road that heads north to Zaporizhzhia. Multiple military checkpoints on the way make it a no-go for Ukrainian men of fighting age. Even women and children face waiting weeks for places on free evacuation buses, or an exorbitant fee for a place in a private car.

But hundreds still flee each day, tumbling off buses or unfolding themselves from crowded, stuffy cars just before dusk into a supermarket car park that doubles as a reception area for those forced into exile in their own country. The adults look exhausted, the children's smiles are timid, as if they're not quite sure whether they're safe yet. Steam gushes from beneath the bonnet of a blue Lada like it's about to explode. After security checks, volunteers offer food and clothes and, for some, there are tearful reunions with waiting relatives.

People fleeing Russian-occupied territory arrive in Zaporizhzhia

We can't travel into Kherson now it's occupied, but the mood in this crowd reveals plenty about life there. Even on Ukrainian-controlled soil, people are wary of what they say. "Will the Russians see this?" some of the new arrivals want to know before I film or even record them speaking. Others shake their heads as I approach, and turn away from my microphone.

"It's tough there, the Russians are everywhere," Alexandra tells me, bouncing baby Nastya on her knee in the back of a car. Inside the aid tent an older woman is standing with two carrier bags at her feet looking lost and lonely. Struggling with tears, Svitlana tells me she's fled Kherson because her nerves are in shreds but her husband has refused to come with her. "He said he's waiting for the Ukrainian army to come and liberate us," she says.

As night begins to fall, and more vehicles pull in, a man admits that his own family are running from more than the missiles. "We know people are disappearing, it's true," he tells me, without giving his name. "In Kherson, you don't go out in the evening."

A resistance poster reads: Zaporizhzhia, land of death to the occupiers

The danger from shelling has increased in recent days, on both sides of the southern frontline.

In Mykolaiv the days usually start with explosions from 4am: down south, the Russian launch sites are so close that the warning siren only goes off after the first missile hits. One morning, sheltering in our hotel basement, I counted at least 20 explosions in the city, some close enough to shake the building. Once the curfew lifted, we found a nearby school in ruins, the playground swings blanketed in the thick grey dust of the collapsed sports hall.

The ruined regional administration building in Mykolaiv

But Ukrainian attacks have also increased, both in number and impact, as more powerful weapons supplied by the West have made it to the region and are making a difference. Residents in Kherson city have recorded multiple strikes on Russian ammunition depots. Bridges across the Dnipro, including the Antonivskiy, have also been hit multiple times, disrupting Russian supply lines.

The push to retake Kherson could be approaching.

Sasha believes many of those who have remained in the city are ready to stay and fight; those I've spoken to say support for Russian rule is minimal and the searches, detentions and beatings in recent months have shrunk that still further.

"When the army starts to invade, then people will be ready and will help," Sasha says.

After his own brutal experience in Russian custody, Oleh is already back on the southern front to fight for his hometown, alongside Ukraine's partisan army.

"They can take the land, but they can't take the people," is how he puts it. "The Russians will never be safe in Kherson, because the people didn't want them there. They don't like them. They won't accept them."

Photographs by Sarah Rainsford. Follow Sarah on Twitter, external