Malta: The only EU country where abortion is illegal leaves women scared

- Published

Pro-choice activists believe an increasing number of women are buying abortion pills online to terminate pregnancy

Alone, in her family bathroom, a woman secretly searches for information about abortion on her phone.

This was Maria - not her real name - after finding out she was pregnant.

"I was scared," she says. "I didn't know what the police [would] do. I thought maybe they would be searching for people googling the word abortion. And then you obviously get paranoid and your thoughts get carried away."

She's speaking to us anonymously because she broke the law by taking pills obtained via an organisation based outside of Malta.

"I filled in a form that a doctor reviews. Then I got an email to actually buy the pills."

Maria says she felt very alone but, in reality, she isn't.

Pro-choice activists believe that an increasing number of women are doing just what Maria did, especially after Covid made travelling abroad for terminations harder.

Using figures from two non-profit organisations, external they calculate that more than 350 abortion pill packs were ordered to Malta in 2021, which can be taken up to the 12th week of pregnancy.

That's despite abortion being an imprisonable offence in the country, with a woman facing up to three years in jail and a doctor up to four - as well as losing their medical license.

However, Maltese media found that no woman has faced criminal charges in years.

Malta is the only EU state that totally bans abortion

It's the only European Union member state with a total ban on the procedure. There are no exceptions, including in cases of rape or incest.

Neither of Malta's main political parties supported a bill to decriminalize abortion last year but campaigners hope that a review of the law, along with shifts in social attitudes, could trigger change.

"Anything that's being looked at is a breath of fresh air," says activist Maya Dimitrijevic, who adds it's a well-known secret abortion pills are arriving in Malta.

Her mother, Lara Dimitrijevic, founded the Women's Rights Foundation, a support and advocacy group in Malta.

They both believe that, slowly, the topic is becoming less taboo.

"It needs to take its time," says Lara. "Up until a few years ago I myself would not publicly give such an interview and talk about abortion so openly."

Activist Maya Dimitrijevic and her mother Lara Dimitrijevic say talking about abortion is becoming less taboo in Malta

Lara is also the lawyer of Andrea Prudente whose case sparked the government review.

The American tourist suffered an incomplete miscarriage while on holiday in Malta. Despite being told that the pregnancy was unviable and that the baby could not survive, doctors wouldn't terminate the pregnancy because there was still a heartbeat.

Fearing the imminent onset of a life-threatening infection, Andrea Prudente was airlifted to Spain. She and her husband Jay now plan to sue the Maltese government.

The case attracted international attention and put Malta's laws under the spotlight.

The government announced a review but there are few details.

"The Maltese law should help doctors do their work," said the Minister for Health, Chris Fearne, in June. "And certainly there should be no part of the law that will preclude doctors or professionals from saving lives."

The BBC approached Chris Fearne for an interview but received no response.

Many expect any change, if it happens, will be very limited rather than a substantial move towards decriminalization. And even if opinion is slowly shifting, particularly amongst the young, surveys suggest a majority in Malta remain anti-abortion, external in this predominantly Catholic country.

In the city of Qormi, they celebrate the feast of Saint Sebastian. Religious festivals like this spring up across Malta through the summer.

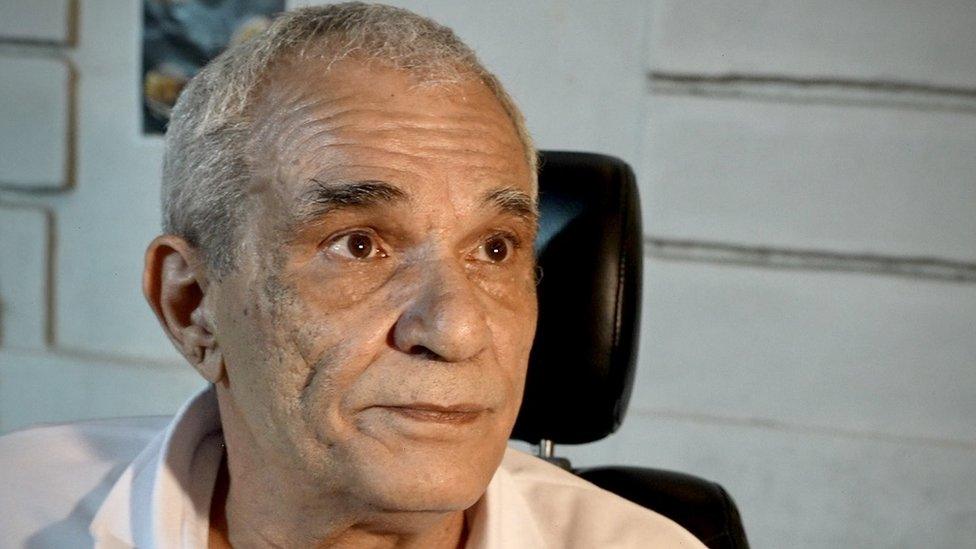

It's there we meet 67-year-old Joseph Saliba, who is enjoying a drink with his family.

Numerous people we spoke to in Malta were reluctant to talk much about this issue, but Joseph is far from shy.

"I'm Catholic and I'm against abortion totally," he tells me. "The baby, he's not going to defend himself."

The Catholic Church has consistently condemned abortion.

Joseph is against abortion but suggests that doctors should act if it is a matter of saving the mother's life

He waves over Christine Azzopardi, who runs the bar across the street and has five children, some of whom cluster around her.

"I am against abortion," the 38-year-old says. "I have five children and I'm a grandma. I love children."

Joseph chimes in passionately, "If she does the abortion, they are not here. Her beautiful children."

However, Joseph suggests that doctors should act if it's a matter of saving the mother's life.

Defenders of the law say that is what happens under what's known as the doctrine of "double effect."

This doctrine effectively states that it's sometimes acceptable to cause harm, as an unintended side-effect, in the course of doing something good.

"When mothers are faced with life threatening conditions then doctors can intervene," says Christian Briffa, from the anti-abortion youth group, I See Life.

He and fellow group member Maria Formosa believe that the law is acting as a deterrent despite no one actually facing criminal charges in years, let alone going to jail.

"If it wasn't for the law there would be more abortions," the 19-year-old Maria insists.

"In Malta we are thankfully one of the few countries that protects both the mother and the child."

Maria Formosa and Christian Briffa from an anti-abortion youth group say if it wasn’t for the law there would be more abortions

Pro-choice campaigners question the legal status, as well as the ethics, of the "double effect" principle.

"It's a doctrine. It's talk," says Professor Isabel Stabile from Doctors for Choice.

"At the end of the day, anyone who has an abortion or anyone who assists someone to have an abortion is liable to breaking the law."

Professor Stabile, a gynaecologist, says these "barbaric" rules also force women, who need post-abortion care, to say they've miscarried.

"But how awful is that, to tell someone to lie about their condition."

She's confident a legal change is coming, "Certainly to accommodate the situation that Andrea Prudente found herself in where there was no chance of viability… and where the woman has made a very clear choice."

Campaigners say they will celebrate even a "small step" and believe more significant change will come within the next 10 years.

The government review is expected to report back later this year.

- Published22 June 2022

- Published24 June 2022