'Walls full of pain': Russia's torture cells in Ukraine

- Published

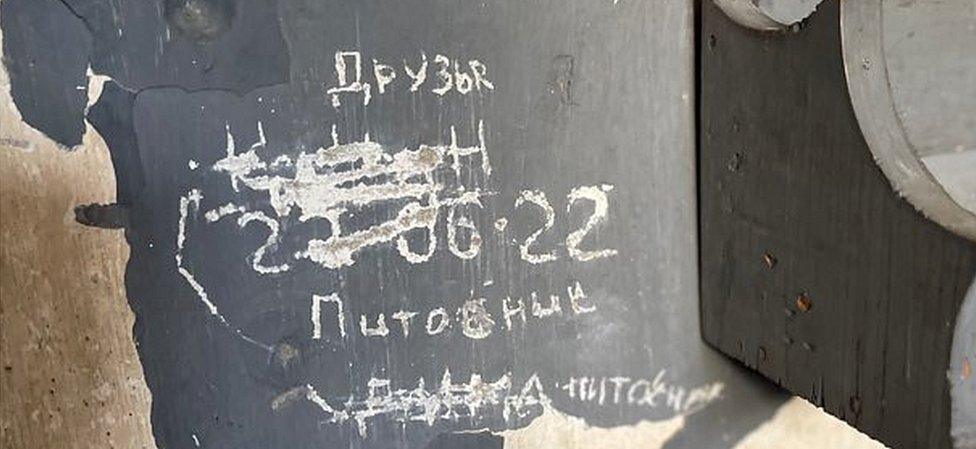

A cell in a prison abandoned by the Russians in Izyum

For those held in the dank basement cells of a makeshift Russian prison in the Ukrainian city of Izyum, there was more than one type of torture. The occupiers had a menu of abuses.

Mykhailo Ivanovych, 67, says he experienced most of them.

WARNING: You may find the following description distressing.

Sitting in a ward in the city's main hospital - which was badly damaged by shelling - the pensioner recounts the abuses he suffered: electrocution, beatings, broken bones and needles inserted beneath the skin.

His left arm is bandaged and in a sling. He is weary, but his voice is unwavering.

"They tortured me for 12 days," he tells us.

"They beat me everywhere. They broke my arm. One Russian was holding it and another one beat it with a pipe. They beat me to the point where I didn't feel anything. They used an electric current on my fingertips - how they burned."

Then there were the needles pushed into his back.

"They were long, and they put them under my skin here and here," he says, gesturing to his shoulders. "I was taken from there half-dead when our forces liberated this place."

That was on 11 September, when Ukrainian forces swept into the city, ending more than five months of Russian rule. During the occupation the Russians used the city as a launchpad for attacks in the eastern Donbas region, and as a key logistics base.

Mykhailo was detained along with others who the Russians suspected of sabotage. The prisoners were hooded, sharing the cramped conditions and the abuse.

"All of those held with me were tortured," he says. "Sometimes they took someone from their cells two or even three times in a day. I saw someone being carried out. I think he was dead."

Mykhailo wears a cross around his neck over a striped T-shirt. I ask if he prayed during his time in the cells. "Of course," he replies. "I had to pray. Anyone would be praying there."

The torture took place in the police station in Izyum. When we enter it is in disarray, with some doors missing and windows blown out. Like much of Izyum it was shelled by the Russians before they took the city.

Darkness closes in as we descend the stairs to two lower floors of cells. Most are small and bare, apart from grimy bedding and some discarded clothing.

In one cell someone has etched lines on the wall, recording the length of their captivity. The silence is broken by a Ukrainian soldier.

"It seems like all these walls are full of pain and suffering," he says.

Mykhailo's account of suffering electric shocks echoes other testimony we have heard recently in newly liberated areas - including from a former journalist called Maxim, who said he was held in the same cells.

"They attach electrodes and connect a current, and you begin to shake," he said. "I was falling from the chair. The pain was too strong. It was pitch black. They tortured us in complete darkness. They had head lamps. I asked my cellmates how long I had been absent, and they told me 40 minutes. I think that you black out after 15 to 20 minutes."

Ukraine is keen to prove that the torture of civilians - a war crime - was systematic, not haphazard. Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelensky says "10 torture chambers" have been found in recent days in areas here in Kharkiv province retaken by Ukrainian forces.

A short distance from the prison we find investigators at work, combing through a damaged office building used by the Russians as their command centre. We are allowed to enter, wearing protective coverings on our shoes, and face masks, so we don't disturb the evidence.

A sign saying "police" in Russian still hangs over the door. Inside on a desk is a thumbed edition of a Russian daily newspaper.

Lead investigator Leonid Pustovit - wearing white protective overalls - has made a grim discovery. He opens a drawer to show us an axe bearing traces of what looks like blood.

"Our investigation will reveal whose blood it is," he tells us.

He has also found a watch-list kept by the Russians, with names of those thought to be supporting the Ukrainian government. "They were called 'the ones with extremist views'," he says. "They brought them here and interrogated them. They were kept on a short leash."

This broken city is just beginning to tell its stories and reveal how many victims the Russians left behind.

In a pine forest on the edge of the city forensic teams are continuing to exhume human remains from more than 440 graves. The authorities say the dead are mostly civilians, but one grave contained the bodies of 17 soldiers, some with their hands bound and bearing signs of torture.

Ukraine is examining bodies found in a mass grave on the edge of Izyum

The regional prosecutor told us the Russians had killed almost all of those buried here - one way or another - including by shooting, shelling or air strikes.

As emergency workers carry away remains in a white body bag, Olena Kazabekhov looks on, caught between hope and dread. She has come in search of her father, Petro Vasylchyshyn, who served with Ukraine's 95th Airborne Battalion. The young woman is tearful, leaning on her husband Yurii for support.

"The last phone call we had was on 17th of April," he tells us. "The next day they moved to the frontline, and many of his unit went missing. We know five were killed. Their bodies were found by another unit."

Tormented by unanswered questions, Yurii says they are almost envious of those who at least have remains to bury.

"We know families that were in the same situation as we are now, but they found the bodies, and they are - it's hard to describe - happier than we are, because at least they found them."

Olena is desperate to find out what happened to her missing father

So far, the military remains unearthed in the forest are of soldiers from a different brigade to his father-in-law's, so he and Olena may have to search elsewhere. For others, the exhumations have already provided answers.

One widely published photo from the burial site showed a decayed hand with blue and yellow bands around the wrist - the colours of Ukraine's flag. A reddish mark was barely visible underneath.

According to a statement on the Facebook page of Ukraine's 93rd Mechanised Brigade, they were the remains of a soldier called Serhiy Sova. When his wife Oksana saw the photo, she recognised the tattoo on his wrist.

Izyum is now a city with deep scars. In every direction there are scorched and battered buildings. The streets are largely lifeless. It's as if residents who survived the shelling and occupation are still scared to come out.

A handful gather in a sunlit square in the city centre to collect some aid being handed out from the back of a van - just small bags of bare essentials. Dasha, 25, is among them, with a lively six-year-old called Tim. She recounts the hardships of recent months, as he chases around the bushes.

"We cooked outside," she says. "The fire truck brought water from the river, but we didn't have drinking water. We went looking for wells so we would have water to drink. Tim was scared to sleep alone. He twitched and had nightmares. The hardest thing was not knowing what tomorrow would bring."

We are still scared... there is no certain victory

The Russians may be gone, but she is still unsure what's ahead.

"We are still scared," she says. "We don't know if we will be safe over the longer term. Military actions are still going on, and there is no certain victory. We're hoping and praying for a peaceful sky and for a bright future for our children."

Having regained so much territory so quickly, Ukraine now has to secure it. Driving around in recent days we have seen convoys of tanks and troops, rushing to plug any gaps, and have occasionally heard incoming fire.

President Zelensky says it's not a lull, but the build-up to the battles to come. "It's preparation for the next sequence," he says, "because Ukraine must be free, all of it."

Dasha has a different phrase for the current situation. "It's thin ice," she says.

War in Ukraine: More coverage

ANALYSIS: Who is winning the war in Ukraine?

ON THE GROUND: What weapons are being supplied to Ukraine?

READ MORE: Full coverage of the crisis, external