Italy elections: Far-right leader Meloni tells Italians 'don't be afraid'

- Published

Giorgia Meloni, 45, could well become Italy's first female prime minister

Pay for two coffees, drink only one. That's the community-minded tradition known as the caffè sospeso.

Those who cannot afford breakfast, pop into their local bar to eat and drink - thanks to the bar owner, plus the kind soul who earlier purchased the sospeso, or "suspended coffee".

The sospeso initiative is said to have started more than 200 years ago in Naples and is now spreading across Italy, where an eye-wateringly strong coffee and accompanying croissant (known in Italy as a cornetto) are viewed as a basic human right of a morning.

Italians, like many others in Europe, are feeling the pinch. Spiralling energy bills compound already existing economic difficulties - hangovers from Covid lockdown measures and the euro crisis.

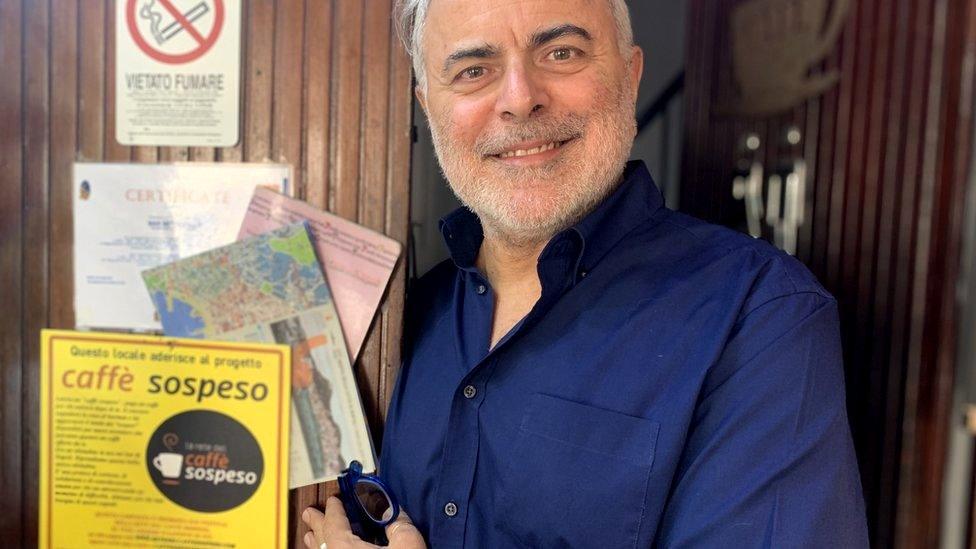

"Italians feel abandoned. Especially here in the south," Pino de Stasio told me. His family have owned Bar Settebello in downtown Naples for decades.

"Unlike the UK, our government hasn't lent us enough of a helping hand. My energy bills have quadrupled. We're forced to switch off our coffee machine at 4pm every day when energy prices spike. So many businesses and families are going under. That's why, unfortunately, people are looking to the [political] right. Because they haven't yet sat in government to disappoint us."

Bar owner Pino de Stasio supports those less well off - but is struggling to pay the bills

This Sunday, 100 years after Mussolini's March on Rome, Italy is poised to opt for a leader from the hard right, whose Brothers of Italy party has its roots in neo-fascism.

Polls in Italy are seen as very reliable indicators. Their key uncertainty appears to be the size of the nationalists' victory.

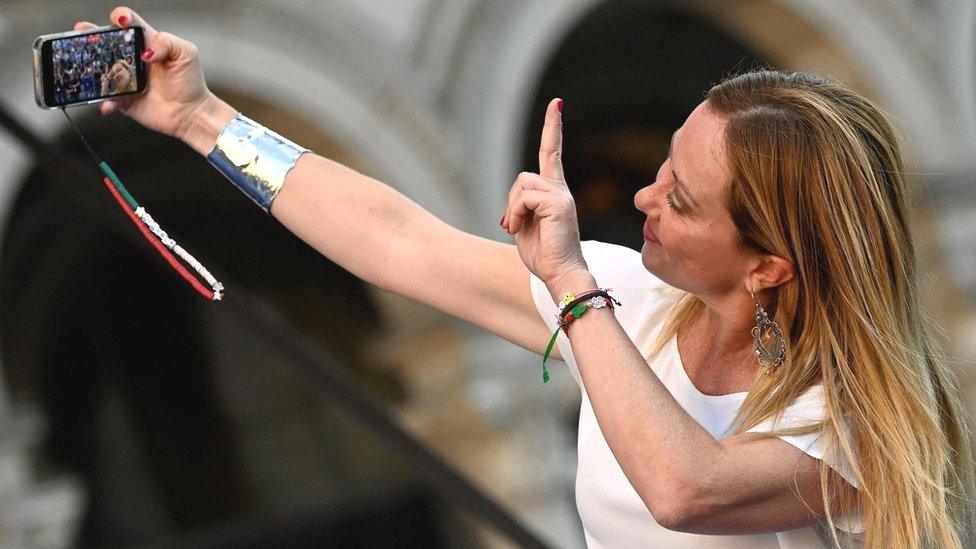

Famous for being small of stature but very loud of voice, Giorgia Meloni was addressing a campaign rally just outside Naples, in the working town of Caserta.

She bellowed her economic promises at the nodding, cheering crowd. She would change Italy, she promised, investing in its strengths, standing up for its interests in Brussels, cracking down on uncontrolled immigration, protecting Italian families and the disadvantaged, while forcing those who can work off benefits.

Giorgia Meloni insists there are no "nostalgic fascists, racists or anti-Semites" in her party

Her supporters say "she makes sense".

While critics fret about her political roots, Ms Meloni knows the money in their pocket - or lack of it - is what Italians care most about right now.

Last election her party got 4% of the vote, now she's angling for her country's premiership. To attract more moderate voters, she's tried to curate a conservative mainstream image.

In an interview with Italy's Corriere della Sera newspaper, Ms Meloni insisted there were no "nostalgic fascists, racists or anti-Semites in the Brothers of Italy DNA", and that she had always got rid of "ambiguous people" from her party.

With her backstreet Roman twang, dressed in slacks and a baggy jumper, her long blonde hair flying as she strode up and down the stage, her intended message was "I'm one of you".

"Don't be afraid," she told the people of Caserta. But that's exactly what voters should be, according to her political opponents.

Caterina Cerroni says the right wing's flat tax rate proposal is an injustice

Caterina Cerroni, 31, is the youngest candidate standing in this election for the left-wing Democratic Party. She said Giorgia Meloni threatened to erode the rights of young people to get a stable job, LGBTQ+ rights and the rights of women - making it harder to get an abortion.

Ms Cerroni also described the right wing's proposal for a flat tax rate as an "injustice, promoting inequality".

"I'd rather have a feminist male prime minister than Italy's first female leader, if she's Giorgia Meloni," she told the BBC.

But bearing in mind the fast-revolving door of Italian governments, many voters we spoke to said their main priority was the durability of Italy's next government.

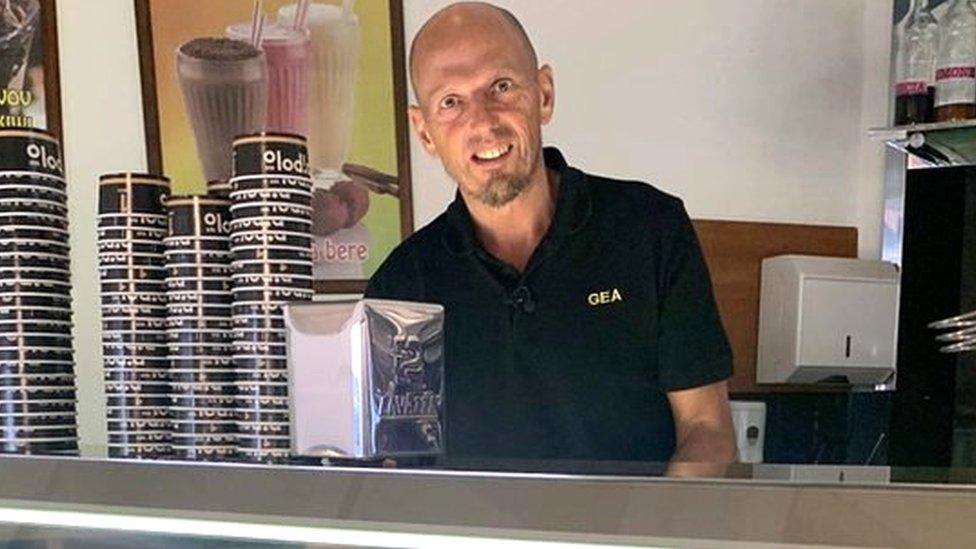

"What we Italians desperately need is stability," bleary-eyed Marco Brozzi told me.

The boss of a small ceramics factory, Ceramiche Noi, in the central region of Umbria, he is tired because he and his workers come in well before dawn these days - to benefit from cheaper energy prices at that time.

Ceramics factories are massively energy intensive and he told me his gas and electricity bills had shot up 1000% over the last year. Unless the new government formed after this election acted fast to help businesses, he said, his factory could face closure within months.

The energy bill for this ceramics factory was said to have shot up by 1000% over the last year

Italy's political system is all about coalition-building and the stability of a Meloni government will depend on how her coalition partners fare in Sunday's vote.

She plans to link arms with centre-right former prime minister and business tycoon Silvio Berlusconi, and with her frenemy and former political rival, the far-right populist Matteo Salvini.

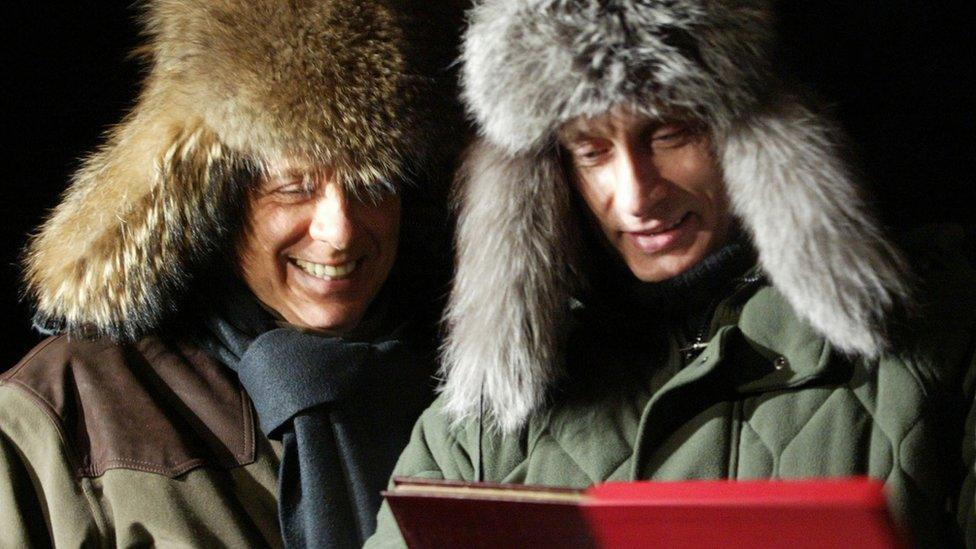

Both men have historically close ties to Russia. Berlusconi once gave Vladimir Putin a bedcover emblazoned with a huge photo of them both. They have even gone skiing together.

This makes Italy's allies in Nato and in Brussels jumpy.

Former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi with Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2003

But Stefano Stefanini, Italy's former ambassador to Nato, told me that where foreign policy was concerned, Italy had been consistent for the past 70 years. The international community should keep an eye on the new government, but also give it a chance, he said.

He pointed out that Ms Meloni was a keen Atlanticist who consistently voted in favour of sanctions against Russia while in opposition: "There's no reason that she'll do different things in government than she's done in opposition."

According to the director of the institute for foreign affairs in Rome, Nathalie Tocci, Ms Meloni is no populist either. Meaning that even if polls indicated Italians wanted their government to drop sanctions against Russia, in response to energy price hikes, she would be unlikely to U-turn on her position.

Italy's post-war, post-Mussolini constitution also contains a number of checks and balances on those in power. President Sergio Matarella will, for example, be able to influence Ms Meloni's choice of government ministers.

If, indeed, she does become prime minister.

- Published22 September 2022

- Published20 September 2022

- Published16 September 2022