Russians said they’d take my baby: A medic’s story

- Published

Late one night in early April, Ukrainian military medic Mariana Mamonova was travelling towards a combat position in Mariupol, south-east Ukraine, with soldiers from her unit.

The fighting was close; the sound of gunfire and bombs came from every direction. One of them could have hit their vehicle at any moment. It was freezing and pitch dark, but at times the sky lit up with what looked like phosphorous weapons, illuminating the road ahead.

Mariana had been serving on the front line in Mariupol since the war began in February, but now the stakes were even higher than usual - she had discovered she was pregnant two weeks earlier.

The city was besieged by Russian forces, bombarded day and night, targeted relentlessly and indiscriminately with Russian missiles.

Her battalion was stationed at the Illich steel plant - one of the city's last Ukrainian holdouts. But the Russians were closing in, and travelling any distance from base meant risking death or capture.

With no safe way of escaping the front line, Mariana had little choice but to stay with her unit despite her pregnancy, and hope for the best for her and her baby. But she was unlucky.

"Our car was stopped and we were told: 'from this moment on you are prisoners of the Russian Federation'," she told the BBC. "'A step to the right, or a step to the left, and we shoot,' they said.

"I turned to the guys I was with and said 'tell me we're not being captured. Tell me they're not taking us prisoner!' I was so scared."

But her worst fears had become reality.

Mariana and her colleagues were transferred to a storage warehouse for three days before being taken to the Olenivka prison in the occupied part of eastern Ukraine.

The facility, notorious for its squalid conditions, abusive staff and chronically overcrowded rooms, was the site of a rocket attack that killed dozens of Ukrainian prisoners of war. Both sides blame the attack on each other.

For Mariana, it was the start of a six-month ordeal during which she slept on the floor and was deprived of access to healthy food and fresh air. She was intimidated and threatened during interrogations and at one point prevented from using the toilet while nine-months pregnant. She was also terrified her baby would be born in captivity and taken from her.

Mariana was taken to a warehouse where she appeared in a video of prisoners published on social media

Soon after she was captured, she was questioned by a Russian official.

"He said if I don't answer the way he needs me to, he'll send me to a camp in Russia and my baby will be taken away," Mariana said.

Her interrogator threatened to ensure that her child was transferred from one orphanage to another, making it impossible to ever track down.

"It was really terrible, I cried so much," she said quietly.

At other times, barking dogs were used to intimidate Mariana into making false statements.

Throughout her ordeal, Mariana's medical training gave her reassurance that her pregnancy was developing normally. But conditions in the prison were poor.

"We lived in a small room meant for six people, but there were 40 women in there," she said.

"The older women slept two or three in a bunk. I slept on the floor, underneath a bed with a friend. I had a couple of pillows and a blanket."

Later, Mariana was transferred to a smaller room where she slept on a wooden pallet on the floor.

For the first few months, she was treated exactly the same as all the other female prisoners. But when she was seven-months pregnant, a doctor advised that she needed more fresh air and she was allowed to walk around the yard.

"It depended on which guard was on shift though," she said. "Sometimes I could spend half a day outside, other times they didn't let me out at all."

In July, she developed a complication and was taken to hospital for an ultrasound. It was Mariana's first glimpse of her baby.

"I saw its little arms and legs. It unfurled its fist and showed me its five little fingers. I cried and cried. They told me the baby was fine, but it was very small and I need to eat more and take more vitamins."

When she returned to the prison, some guards took pity on her and brought her home-cooked food and vitamins.

Mariana's husband, Vasyl, campaigned for her release

As Mariana entered the final weeks of her pregnancy, there was talk of a prisoner swap but still no sign of it happening.

Her husband Vasyl, frustrated at a perceived lack of urgency from the Ukrainian government in negotiating her release, appealed for her to be freed on humanitarian grounds.

"A mother and her children are sacred everywhere... Let them free her," he told the BBC just days before her release.

Mariana was transferred to a maternity ward in Donetsk where she was treated well, but the threat of being separated from her baby remained.

Two possibilities emerged; either Mariana would be sent to a prison in Donetsk where she could live with her baby for as long as she was breastfeeding. Or she would be taken to a facility in Russia where her baby would be taken from her when it turned three. She was too scared to ask where her child would go in either scenario.

Mariana felt that an exchange was her last hope. But one Friday in September, she received the news she had been dreading.

"They told me the exchange was off. The situation on the frontline had intensified, and the two sides couldn't agree. I understood it was the end," Mariana said. By then she could have given birth any day.

But over the weekend, something changed. Mariana doesn't know why but all of a sudden the swap was given the green light.

Mariana appeared heavily pregnant in a video of the prisoner exchange

The following Tuesday, she was transferred with dozens of other prisoners to a city in Russia near the Ukrainian border. There, she was blindfolded, her hands tied, and put on a military plane with other prisoners to a location in Belarus.

The journey took 20 hours but the Russian soldiers guarding Mariana refused to let her use the toilet, despite her being nine-months pregnant.

"'Use this bottle,' they joked. I told them 'I won't be able to get it in' and 'I'm in pain'. But they just told me to hold it in," Mariana said with a resigned laugh.

From Belarus she was driven the short distance across to the border to Ukraine, and she was back in the relative safety of her homeland.

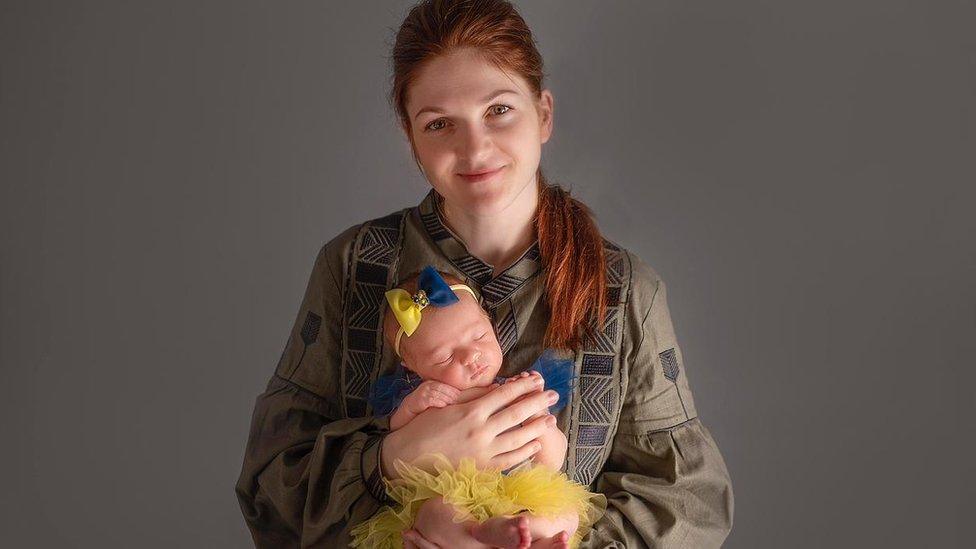

Just four days later, Mariana gave birth to a healthy baby girl called Anna. She weighed 3.2kg (7lb) - within the normal range.

As for the future, Mariana would like to continue working in medicine, but her husband has made his views clear.

"He says he won't cope if I go back to the front line," she laughs. "He said he'd leave me." For now, the couple are content adapting to their new life as a family.

"I already got used to the fact that I have a little baby, who has completely changed my life," she said. "I even had time to get used to the idea of being a mum. It's just unfortunate that I had to do that in prison."

Anna was born just four days after Mariana was released

Related topics

- Published9 September 2022

- Published17 May 2022