Nagorno-Karabakh: Empty shops and blockade pile pressure on Armenians

- Published

There is no food for sale in Stepanakert and ethnic Armenians have gone without new supplies for weeks

"Shops are empty and in the whole town, you can't find any fruit or vegetables; the same with basic medicine. It's all finished," says Marut Vanyan.

All supplies to his home city of Stepanakert and the villages that surround it have stopped, because the only road in has been blockaded for 26 days.

Stepanakert lies in the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh inside Azerbaijan.

Even its name is contested.

Azerbaijan calls it Khankendi, but it is populated exclusively by ethnic Armenians.

"I live right next to the main market which supplies the city, and it's been closed for some time; there are just two ladies sitting there selling dried thyme," Vanyan, a journalist, told the BBC over the phone.

The only route for food, medical supplies and people into areas controlled by ethnic Armenians is via a road known as the Lachin corridor. It is the only link between Karabakh and the Republic of Armenia.

For close to four weeks, the road has been blocked by Azerbaijani protesters who have set up tents outside the town of Shusha. This city, which overlooks Stepanakert, was retaken by Azerbaijan in a war in 2020 with Armenia for control of the region.

The protesters, who describe themselves as environmental activists, are demanding access to mining sites inside Karabakh.

Azerbaijan's TV channels are leading their news bulletins with live reporting from the scene. Well-organised protesters chant and hold placards with slogans such as "Save Nature".

In a country where grassroots demonstrations are quickly suppressed, the blockade of the Lachin road appears to have the full backing of the authorities.

Armenia and Azerbaijan fought a six-week war in 2020 over the enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh and surrounding territories.

Thousands died in a conflict that led to Azerbaijan taking back much of its land that had been under Armenian control since the 1990s. But the status of the Karabakh enclave itself remains unresolved.

Now a contingent of Russian peacekeepers deployed to Karabakh after the war in 2020 is all that stands between ethnic Armenians inside the enclave and Azerbaijani forces who have regained control of the surrounding territories.

But the peacekeepers seem powerless to break the blockade. Russia, which has its hands tied in its war in Ukraine, has been unable to resolve the standoff.

Azerbaijan's state-controlled media promote the narrative that Russian peacekeepers are failing to prevent illegal mining and turning a blind eye to military equipment entering the enclave.

The foreign ministry in the capital, Baku, has denied that the closure of the Lachin corridor has created a humanitarian crisis.

Protesters and Azerbaijani media promote a narrative of illegal mining in the Lachin corridor

The ministry insisted on Wednesday that the road was still open for Russian peacekeepers, the Red Cross and medical vehicles, adding that the government of Azerbaijan was ready to solve all the humanitarian needs of its Armenian residents.

But Armenia believes the environmental protesters are simply a cover, to put pressure on ethnic Armenians living in Karabakh and to force them to accept Azerbaijan's sovereignty over the region or leave.

Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan wants the international community to send a fact-finding mission to the region. Meanwhile, the de facto Armenian authorities in Karabakh have called for an air bridge to help deliver essential food and medicine to the population.

Marut Vanyan describes visiting a local hospital in Stepanakert this week, where he found a young mother splitting adult pills to give to her sick child as the hospital no longer had medication for children.

He complained that the Lachin corridor blockade was the latest privation that ethnic Armenians had suffered since Azerbaijan's victory in the war.

"For the past two years, we've had constant problems with electricity, water and gas. When we have water, there is no gas, something is always missing. But it is secondary to the difficulties we have now with shortages of food and medicine."

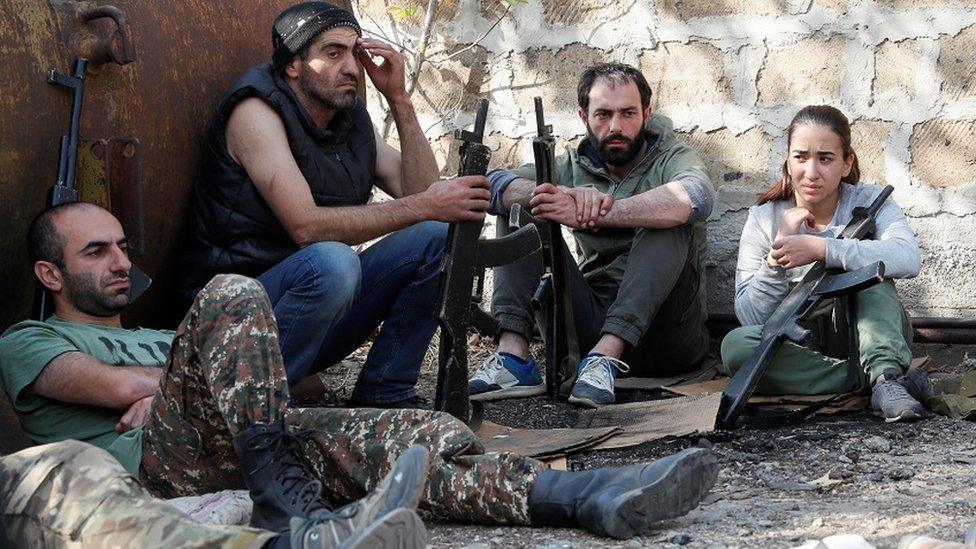

The blockade was causing immense psychological pressure for residents, he said, after a war that had left every family without a son, husband or brother.

"The guns are silent now, but the war continues."

- Published12 November 2020

- Published10 November 2020

- Published14 October 2020