Ukraine war: Hiding from Putin's call-up by living off-grid in a freezing forest

- Published

Adam Kalinin has lived in the Russian wilderness for nearly four months to avoid being called up to fight in Ukraine

When Vladimir Putin announced a partial mobilisation of Russian men in September last year, it took Adam Kalinin - not his real name - a week to decide that the best thing he could do was move to the forest.

The IT specialist was against the war from the start, receiving a fine and spending two weeks in detention for sticking a poster saying "No to war" on the wall of his apartment building.

So when Russia said it was calling up 300,000 men to help turn things around in a war it was losing, Kalinin did not want to risk being sent to the front line to kill Ukrainians.

But, unlike hundreds of thousands of others, he did not want to leave the country.

Three things kept him in Russia: friends, financial constraints and an unease about abandoning what he knows.

"Leaving would have been a difficult step out of my comfort zone," Kalinin, who is in his thirties, told the BBC. "It isn't exactly comfortable here either but nevertheless, psychologically, it would be really hard to leave."

And so he took the unusual step of saying goodbye to his wife and heading for the forest, where he has lived in a tent for nearly four months.

He uses an antenna tied to a tree for internet access and solar panels for energy.

He has endured temperatures as low as -11C (12F) and exists on food supplies brought to him regularly by his wife.

Living off-grid, he says, is the best way he can think of to avoid being called up. If the authorities can't hand him a summons in person, he can't be forced to go to war.

"If they are physically unable to take me by the hands and lead me to the enlistment office, that is a 99% defence against mobilisation or other harassment."

In some ways, Kalinin continues his life as before. He still works eight hours a day in the same job, although throughout winter - with its limited daylight - he doesn't have enough solar power to work full days and so makes up his hours on the weekend.

Some of his colleagues are now in Kazakhstan, having also left Russia after mobilisation began, but his internet connection via a long-range antenna strapped to a pine tree is reliable enough that communication is not a problem.

He is also a lover of the outdoors, spending many of his past holidays camping in southern Russia with his wife. When he made the decision to move permanently to the wilderness, he already had much of the equipment he needed.

Kalinin says he doesn't know how much longer he will stay in the forest

His wife, who visited Kalinin's camp for a couple of days over the new year, plays a big role in his survival. She brings supplies every three weeks to a drop-off point where they are briefly able to see each other in person. He then takes the supplies away to a safe place which he visits every few days to stock up. He cooks using a makeshift wood-burning stove.

"I have oats, buckwheat, tea, coffee, sugar. Not enough fresh fruit and vegetables of course, but it's not too bad," he says.

Kalinin's new home is a large tent of the type used for ice-fishing. When he first arrived in the forest, he set up two camps five minutes apart; one with internet access where he worked, the other in a more sheltered spot where he slept.

As winter approached and the weather got colder, he brought the two areas together to live and work under one canvas.

Recently, the temperature dropped to -11C, colder than he had expected. But now the days are getting longer again and the snow is beginning to melt, he plans to stay where he is.

Although Kalinin hasn't received a call-up himself, he says the situation is constantly changing and he fears he could receive a summons in the future. Officially, IT workers like Kalinin are exempt from the draft, but there are numerous reports in Russia of similar exemptions being ignored.

Russian President Vladimir Putin announced the mobilisation on 21 September, shortly after Ukraine's lightning counteroffensive in the Kharkiv region during which it reclaimed thousands of square kilometres of territory from Russian troops.

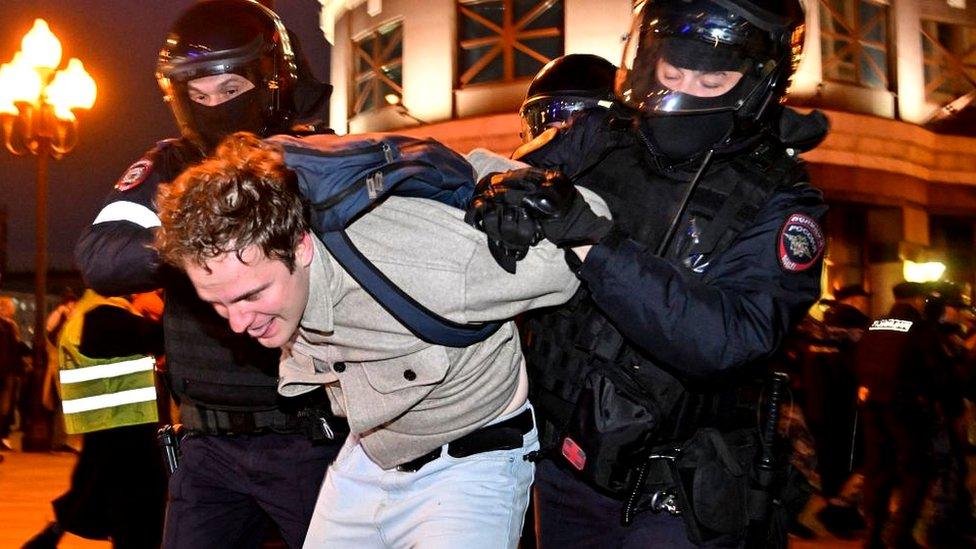

He said the mobilisation was necessary to defend Russia against the West. But many in the country protested, and there were chaotic scenes on Russia's borders as hundreds of thousands of people fled.

The call-up had a profound effect on Russia. Until then, many Russians were able to continue their lives much as they had before the war. True, some Western brands disappeared and sanctions made financial transactions more difficult, but the direct impact on society was mostly limited.

Mobilisation brought the war crashing on to the doorsteps of many Russian families. Suddenly, sons, fathers and brothers were deployed to the front line at short notice, often with poor equipment and minimal training. If the conflict seemed distant before, now it was all but impossible to ignore.

Yet, public acts of protests are rare inside Russia - something that has been criticised in Ukraine and in the West. But Kalinin says people are rightly scared of what might happen to them.

"We have a totalitarian state that has become so powerful. In the last six months, laws have been brought in at an incredible pace. If a person speaks out now against the war, the state will pursue them."

An ice-fishing tent is Kalinin's space for work and sleep

Kalinin's life in the forest has brought him a certain level of popularity online, with 17,000 people following his near-daily updates on Telegram, external. He posts videos and photos of his surroundings, his daily routine, and of how his camp is organised. Wood-chopping features heavily.

Kalinin claims not to miss much about his previous life. He calls himself an introvert who doesn't mind being alone, although he misses his wife and would like to see her more often. However, he points out that his current situation is still preferable to being sent to the front line or to prison.

"I've changed so much, that the kind of things I might have missed have faded into the background," he says. "The things that seemed important before don't have their power any more. There are people in a much worse situation than us."

The snow is beginning to melt as the days get longer, Kalinin says

Related topics

- Published22 September 2022

- Published21 September 2022