Ukraine war: Why Bakhmut matters for Russia and Ukraine

- Published

Russia has virtually destroyed Bakhmut in its attempts to seize the city

Bakhmut lies in ruins.

For more than seven long months, this small industrial city in eastern Ukraine has been pounded by Russian forces.

According to its deputy mayor, Oleksandr Marchenko, there are just a few thousand civilians left living in underground shelters with no water, gas or power. "The city is almost destroyed," he told the BBC. "There is not a single building that has remained untouched in this war."

So why are Russia and Ukraine fighting so hard over this pile of rubble? Why are both sides laying down the lives of so many of soldiers to attack and defend this city in a battle that has lasted longer than any other in this war?

Military analysts say Bakhmut has little strategic value. It is not a garrison town or a transport hub or a major centre of population. Before the invasion, there were about 70,000 people living there. The city was best known for its salt and gypsum mines and huge winery. It holds no particular geographic importance. As one Western official put it, Bakhmut is "one small tactical event on a 1,200-kilometre front line".

And yet Russia is deploying huge military resources into taking the city. Western officials estimate between 20,000 and 30,000 Russian troops have been killed or injured so far in and around Bakhmut.

Ukraine has suffered many casualties - such as this soldier being buried in Lviv - in its defence of Bakhmut

The Kremlin needs a victory, however symbolic. It has been a long time since the summer when Russian forces seized cities like Severodonetsk and Lysychansk. Since then what territorial gains they have made have been incremental and slow.

So Russia needs a success to sell to pro-Kremlin propagandists back home. Serhii Kuzan, chairman of the Ukrainian Security and Co-operation Centre, told the BBC: "They are fighting a political mission, not a purely military one. Russians will continue to sacrifice thousands of lives to achieve their political goals."

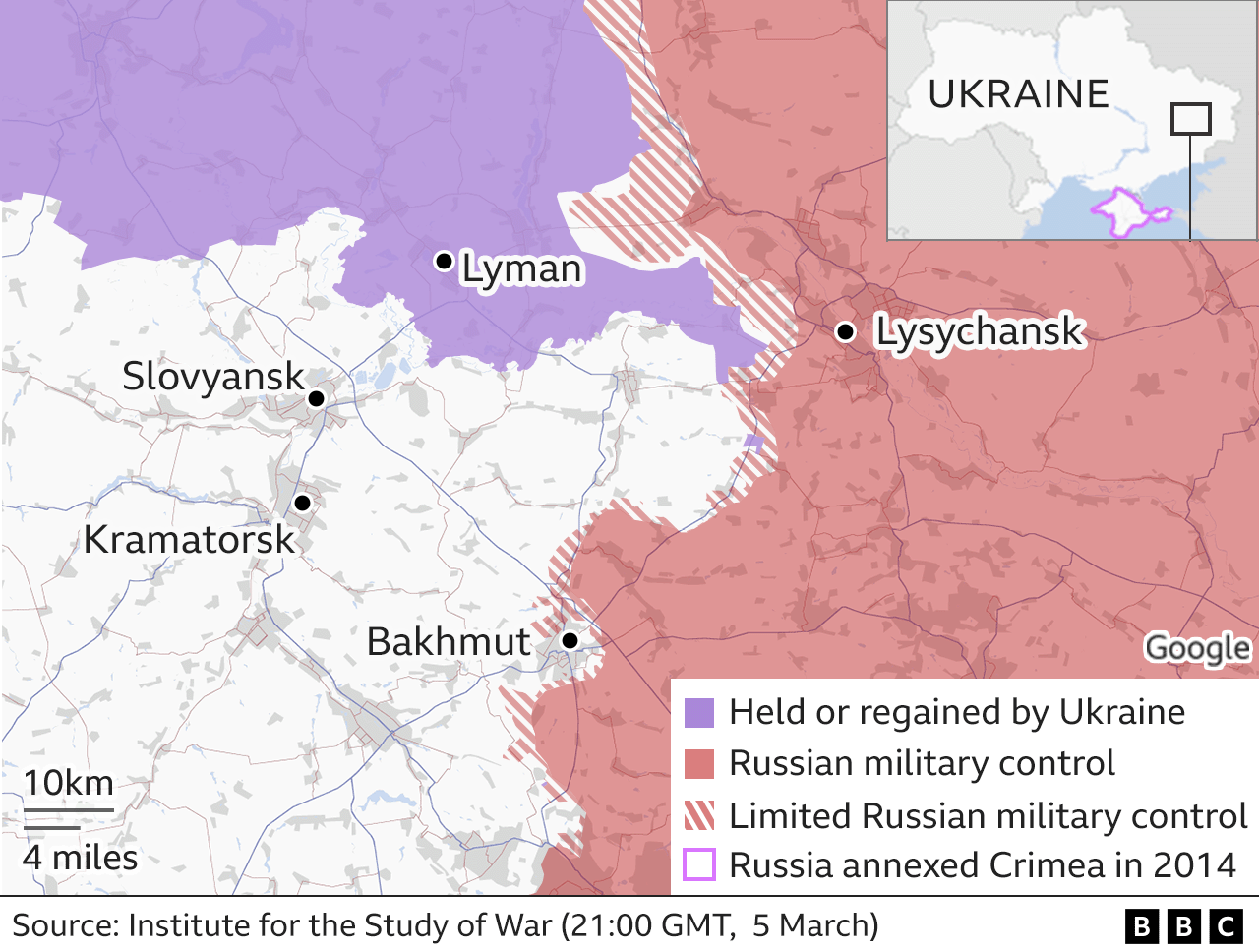

Russian commanders also want to take Bakhmut for military reasons. They hope it might give them a springboard for further territorial gains. As the UK Ministry of Defence noted in December, external, capturing the city "would potentially allow Russia to threaten the larger urban areas of Kramatorsk and Sloviansk".

And then there is question of the Wagner mercenary group that is at the heart of the assault.

Its leader Yevgeny Prigozhin has staked his reputation, and that of his private army, on seizing Bakhmut. He hoped to show his fighters could do better than the regular Russian army. He has recruited thousands of convicts and is throwing waves of them at Ukrainian defences, many to their deaths.

If he cannot succeed here, then his political influence in Moscow will diminish. Mr Prigozhin is at odds with Russia's defence minister, Sergei Shoigu, criticising his tactics and now complaining about not getting enough ammunition. There is, Mr Kuzan said, a political struggle between both men for influence in the Kremlin "and the place for this struggle is in Bakhmut and its surroundings".

Few civilians remain in Bakhmut, which was once home to about 70,000 people

So why has Ukraine been defending Bakhmut so doggedly, losing thousands of troops in the process?

The main strategic purpose is to use the battle to weaken Russia's army. One Western official put it bluntly: "Bakhmut, because of the Russian tactics, is giving Ukraine a unique opportunity to kill a lot of Russians."

Nato sources estimate five Russians are dying for every one Ukrainian in Bakhmut. Ukraine's national security secretary, Oleksiy Danilov, says the ratio is even higher at seven to one, external.

These numbers are impossible to verify. Serhii Kuzan told the BBC: "As long as Bakhmut fulfils its function, allowing us to grind down the enemy's forces, to destroy much more of them proportionately than the enemy inflicts losses on us, until then we will of course keep on holding Bakhmut." By defending the city, Ukraine also ties up Russian forces that could be deployed elsewhere on the front line.

Like Russia, Ukraine has also given Bakhmut political significance. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has made the city an emblem of resistance. When he visited Washington in December, he called it "the fortress of our morale" and gave a Bakhmut flag to the US Congress. "The fight for Bakhmut will change the trajectory of our war for independence and for freedom," he said.

The battle for Bakhmut has raged for months

So what if Bakhmut falls? Russia would claim a victory, a rare piece of good news to bolster morale. Ukraine would suffer a political, symbolic loss. No longer would Ukrainians be able to cry "Bakhmut holds!" on social media. But few believe there would be a huge military impact. The US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin said: "The fall of Bakhmut won't necessarily mean that the Russians have changed the tide of this fight."

Mick Ryan, a strategist and former Australian general, believes there would be no fast Russian advance, external: "The Ukrainians… will be withdrawing into defensive zones in the Kramatorsk areas that they have had eight years to prepare. And the city sits on higher, more defensible ground than Bakhmut. Any advance on the Kramatorsk region is likely to be every bit as bloody for the Russians as its campaign for Bakhmut."

So perhaps what matters most in the battle for Bakhmut are how many losses each side has incurred and what that might mean for the next phase in this war. Will Russia have suffered so many casualties that its capacity to mount further offensives will have been weakened? Or will Ukraine have lost so many soldiers that its army would be less able to launch a counter-offensive later in the spring?

Related topics

- Published24 February 2023

- Published7 March 2023

- Published5 March 2023