How will Irish government spend corporation tax windfall?

- Published

Look at the shareholder register for most of the world's biggest companies and one name which appears again and again is Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM).

NBIM is the operational arm of Norway's sovereign wealth fund.

It was set up in 1996 to invest tax revenues from the country's oil industry.

The aim was to turn those finite oil revenues into long-term resources for the Norwegian people.

It does that by essentially owning a little bit of everything in the global economy. It is a shareholder in more than 9,000 publicly traded companies and its assets are worth more than $1 trillion (£803 billion).

Ballooning tax receipts

Now the Irish government is planning to do something similar, albeit on a much smaller scale.

The Republic of Ireland raised €22.6bn in corporation tax in 2022

The Irish exchequer is currently awash with revenues from corporation tax and it is that, rather than oil money, which will be used to build the fund.

Partial reforms to global tax regulation have had the unintended consequence of large US companies paying tax on much of their global earnings in Ireland.

This has seen corporation tax receipts in Ireland balloon from just over €4bn (£3.5bn) in 2014 to more than €22bn (£19.3bn) last year. The tax take is so large that the country is now able to run a substantial budget surplus.

However, the expectation is that at least some of this revenue is transitory, so it cannot be relied upon to fund permanent spending increases or tax cuts.

This week Irish Finance Minister Michael McGrath said it was therefore "blindingly obvious" to him that the corporation tax windfall should be used as an investment fund, adding that it is a "once in a generation" opportunity.

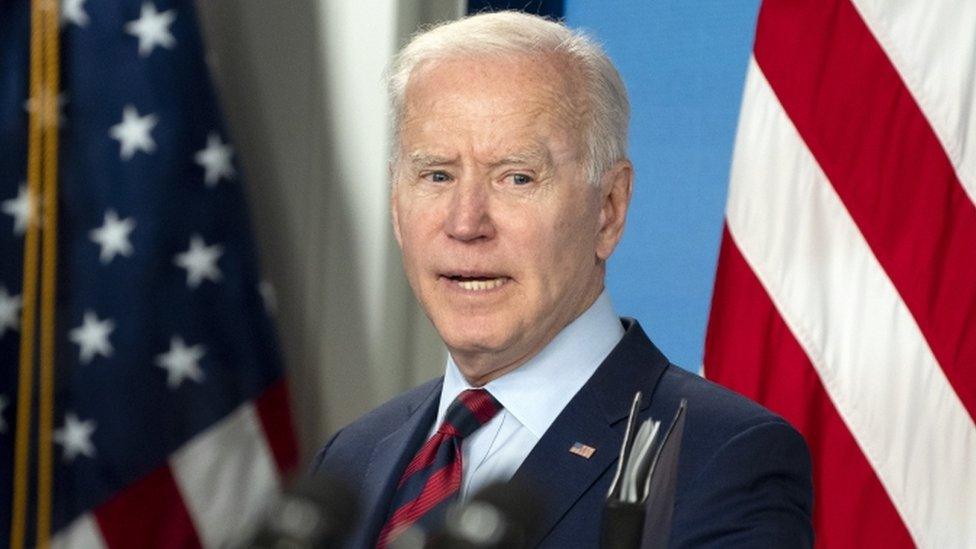

Finance Minister Michael McGrath believes the corporation-tax windfall should be used as an investment fund

A 'scoping document' from his department, external contains a brief reflection on the contrasting experiences of Norway and the UK in terms of how they used their North Sea oil windfalls.

Cautionary message

It describes how the UK used the money to reduce income tax and corporation tax rates during the 1980s. By contrast, Norway is described as taking a "more fiscally prudent approach".

This is, perhaps, a cautionary message to colleagues of Mr McGrath who would prefer a tax-cutting splurge ahead of the next election.

The scoping document also draws on the experience of long-term saving funds in Australia, Japan and Estonia.

It also notes that Ireland already has some experience of trying to save for a rainy day: a National Pensions Reserve Fund was established in 2001.

However, before the end of the decade it was almost entirely consumed by the economic deluge of the Irish banking crisis.

A successor fund, the National Reserve Fund (NRF) was established in 2019 but its initial capital of €1.5bn (£1.3bn) was soon called on to deal with the impacts of the Covid pandemic.

It has been recapitalised with €6bn (£5.2bn) of the corporation-tax windfall but the current remit of the NRF is limited.

It has an investment ceiling of €8bn (£7bn) and is intended to hold financial assets which can be drawn upon quickly in an emergency.

So Mr McGrath has essentially laid out some options for repurposing the NRF.

The most ambitious plan would involve an initial €18bn (£15.8bn), consisting of the NRF's existing resources and €12bn (10.5bn) of corporation-tax windfall, with a further €12bn pumped in every year between 2024 and 2030.

Under all the options, annual returns would be reinvested until drawdowns begin some time after 2030.

Mr McGrath also set out some options for the rules for drawing down money from the fund.

The preferred option would be to follow the Norwegian example and have a rule where drawdowns cannot exceed the expected real return on the capital in the fund, to avoid it being depleted over time.

Then there is the question of what any drawdowns would be spent on.

Higher taxes still possible

The intention laid out in the scoping document is that the money should be focused on what are described as age-related costs. Those are things such as the rising cost of healthcare and state pensions for an ageing population.

The document says this approach would "reduce impending budgetary costs and, in doing so, smooth the impact on the public finances and promote inter-generational equity".

But there is also a warning that even in the best case scenario, the fund will not produce a big enough return for Ireland to completely dodge the demographic bullet.

The paper concludes that the fund would have to be seen as "a complement to, and not a substitute for, other necessary reforms", which could include higher taxes.

Related topics

- Published23 April 2023

- Published8 April 2021